Willy Wenger's Writings

- 4081 reads

Leopold Wenger's Childhood

- 3089 reads

Childhood

By Willy Wenger

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

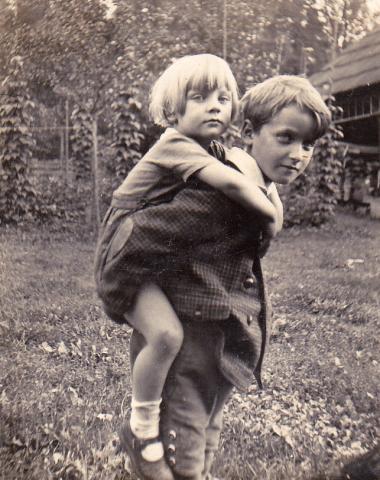

The young Wenger family in 1928 - Bibi is 6, Willy 2

Our father Leopold Wenger was born 1893 in Bad Gleichenberg, Styria, Austria. Our mother Grete was born in 1896 in Marburg, Styria and became a teacher in the primary school in Bad Gleichenberg.

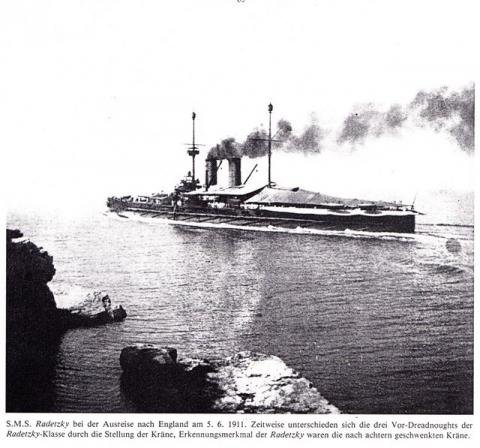

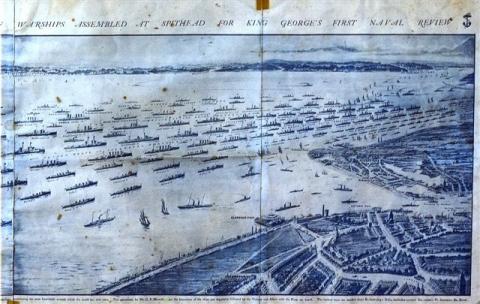

When 14 years old, my father (pictured right) entered into the 4-year technical high school of the Austrian Imperatorial and Royal Navy (Maschinenschule der österr. k+k Kriegsmarine) from where he obtained the license of a leading engineer. The school was located at the Navy's first harbour in Pola (today Pula, Croatia). He took part in the great naval parade in Plymouth during the coronation of George V in June 1911, on board the Austrian battleship “Radetzky.” At that period the Austrian navy was 5th or 6th in the world. More than 200 ships had been anchored in front of the South Coast near Spithead. All maritime nations had been invited to send warships to represent themselves, and it was the most gigantic show of the fleet ever seen.

Above: The Austrian battleship S.M.S. Radetzky arrives to England on May 6, 1911, with Leopold Sr. as part of the crew.

Above: Warships assembled at Spithead for King George's first naval review.

My father was very unhappy when, after WWI, Austria lost its access to the sea. For him the sea had become his homeland. He thus named his small house in Bad Gleichenberg Seemannslos, “the refuge of a sailor,” situated in South-eastern Styria, not far from the Hungarian border to the east and the Slovenian border in the South. The countryside is agreeably hilly, topped by churches, Chateaux, castles—giving an idyllic and romantic look.

At right: The castle of Riegersburg - one of the most beautiful in Europe.

Agriculture is the main industry, with many apple orchards, vineyards in the southern part, corn all over, hot radish, and well known for its pumpkin seeds.

"Seemannslos" in Bad Gleichenburg as it is today, now Willy's home.

Leopold Jr. was born on 19 November 1921 in Graz, the capital of Styria, two years after the humiliating Treaty of St Germaine, which came to us as the result of the First World War. The great Austrian Empire was dismembered due to the hatred of the “Big Three,” President Wilson (USA), Lloyd George (UK) and Clemenceau (France). What remained was a small country which, even though it could call itself a German-Austrian Republic, could not join the German Reich. The result was chaos. The new government was aware that they could not govern independently due to the lack of experience—up to then the Habsburgs had ruled in the land. The politicians quarreled among themselves so much that eventually most people wished to join Germany.

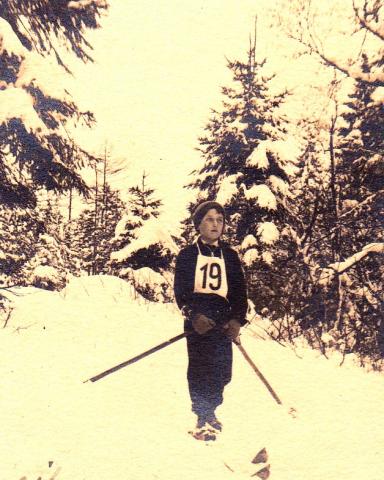

Little Leopold's nickname “Bibi” came about because he could not pronounce the word “Bubi,” (Bub is a young boy in German). Bibi grew up in the town of Anger in Eastern Styria. He loved winters. Skiing in the hilly region was then a rarity, but for Christmas Bibi got a couple of small-size skis and was a sensation. His schoolmates managed to try this new sport by taking staves out of old wine barrels they got from the barrel maker and fixing the staves onto their shoes. They cut long sticks from the hazelnut bushes to help them keep balance and control direction, and off they went.

Bibi with older schoolmates in Anger. Staves from old wine barrels served as skis for them.

On 6 May 1926 Bibi got a little brother, Willy. In 1929 our parents moved to Leoben in Upper Styria, where our father became a manager of a roofing and sheet-metal company. Bibi finished elementary school and entered the Gymnasium. Willy went to kindergarten in the same building.

"He ain't heavy - he's my brother."

At that time, Austria was still in a troubled and rotten shape. The unemployment rate was particularly high. On top of that, there were almost always demonstrations somewhere because of the great number of political parties. There were the Socialists, the Christian Democrats, the Schutzbund, the National Socialists, the Fatherland Front (founded by Dollfuss), Christian Social, and the Communists—all fighting each other. But almost all the parties were in agreement as to a union with Germany. In Tyrol and Styria there were referendums and everywhere the majority voted for a union with Germany.

In Leoben, there were many popular entertainment events, and especially sports and social ones. The German Sports Association, well organized and popular, stood behind many of the events. There was a big field in Leoben and all the sports enthusiasts met there. In the “valley” at a nearby mountain range, people of all ages participated in physical exercises and gymnastics.

Circus Wickl-Wackl with Dad's animal models - the entertainment was necessarily of the home-grown variety.

In the summer, there was a sports festival with various demonstrations of athletes, and our own "Zirkus Wickl-Wackl” was a great amusement. Everything was prepared by us. As our father was a pretty clever model maker, he created a number of papier mâché circus animals and painted them in bright colors. In the summer, the Sports Association organized the rallies of gymnasts. In the winter, the gymnasts showed off their skills in the great hall of the Hotel Post. Of course, there were competitions in skiing and these were extremely popular. And during the carnival there were always masked balls for young and old.

Bibi takes third place in the Leoben Downhill Race

Bibi - a determined competitor

We were members of the German Gymnastics Association. At the first ski race, Bibi scored 3rd place. When the Olympic Games of 1936 took place in Berlin, we wanted to emulate all the athletes. We listened enthusiastically to the radio and looked longingly to Germany which, after Hitler came to power, went through a great change, leaving us sad for ourselves, and jealous.

My Aunt Hilda was a spectator at the Olympics in Berlin and we listened with great interest to her description of all the innovations which she had seen. The new government under Adolf Hitler had done incredible things since 1933. Berlin presented itself as a very clean city. Many old houses were renovated, testifying to the reconstruction in all the German Reich. Unemployment disappeared. It was hard to take in how much the new regime had done in the short time of less than three years, and after such a difficult time.

That was the moment, perhaps the motivation, for my brother Bibi to join the illegal Hitler Youth. Also our father joined the NSDAP, although this party was banned in Austria. They had not said anything to me about it because they considered me too young.

Once a Zeppelin came floating over Leoben. We had excitedly followed its air travel through Austria and burst into joy when we saw this technical wonder hovering above us. On another occasion, a huge bus from Germany arrived in the main square. Inside was an exhibition about the German regions. There were many pictures showing people's lives, their houses, what they had achieved in the recent times. One could take very large brochures for free. We were speechless. You could see workers who were able go on vacations with their families through the KdF (Strength through Joy) program—trips on cruise ships like the "Wilhelm Gustloff" to the Canary Islands. We liked it very much and looked with envy to our neighboring country.

Below, Bibi and Willy at the house in Bad Gleichenberg in 1932 - always best friends.

Category

Germany, Leopold Wenger, Willy WengerThe Anschluss of Austria

- 6703 reads

This report comes from a family chronicle that describes events during the so-called "Nazi era" as we experienced it. It is a testimony to great idealism and sacrifice for an Idea which filled us then. Today, most people see things in a very different light ...

The great hope: the German Reich

By Willy Wenger

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Hasso Castrup

Eisenerzer Alps, January 1938

We got through the winter of 1937 well. We often traveled to our skiing places. I was usually in the company of my schoolmates; Mandi Holzer was always there. Poldi [Willy's older brother Leopold whom he called Bibi-cy] preferred the higher regions of Vordernberg auf den Polster (a popular ski resort, easy to reach from Leoben).

At the tender age of 12 there is a lot one doesn’t understand, but it still always aroused our interest when older students gathered during breaks at school and discussed the situation at that time. Again and again we were talking about Germany, for us a promised land flowing with milk and honey. While in Austria we still had a very modest standard of living, it seemed to go better and better in Germany. And that was thanks to one man: Adolf Hitler. One spoke of him as a god, who had pulled Germany out of the sump after the shameful Treaty of Versailles. Gradually Hitler brought back former German territories. And all this without bloodshed. It actually seemed as if there really was to be "no more war!"

Again and again the question was raised whether Austria was actually able to exist independently. And, increasingly, one doubted that and wanted to join the German Reich. The system which Germany applied was convincing. People wanted to be able to express their German nationalism and saw in Hitler's strong personality the ability to resolve all grievances and restore order. Many communities of nationally-minded Germans soon formed. People met secretly and joined the Nazi party, which was strictly forbidden in Austria.

Hitler was able to attain control over the citizenship. Within the ranks of NSDAP all interest groups were working together. Even before the takeover of power he created a group of followers who smoothed the way during numerous speeches: the storm troopers, known as SA. Later, a separate Protection Squad, the SS, was created. The workers were united in the DAF. Automobile and, above all, motorcycle owners were united in the NSKK. Those interested in aviation could join NSFK (Flying Corps). Particular emphasis was put on the youth. The boys from 10 years of age belonged to “Jungvolk,” the so-called “Pimpfe,” and the 14 to 18 year-olds were members of the “Hitler Youth” (Hitler Jugend - HJ). It was similar among the girls - they were all members of the League of German Girls, the BDM. There were a number of well-organized units in many spheres of life, like the TN (Technical Emergency) – a kind of fire squads, ready for disaster assistance. The political work was in the hands of political leaders who were in charge of local and regional groups. And, not least, the German women were organized in the National-Socialist Women (NS-Frauenschaft). This allowed the whole system to be well-controlled and guided. In Austria, many such organizations had been founded throughout the years, but, as mentioned, they were illegal. Yet, the illegals met quite regularly. Poldi was a member of the illegal HJ. In 1937, fifteen years old, he bicycled on his own to a summer camp of the banned Hitler Youth at Turnersee in Carinthia. He then rode his bike all the way to Germany and met with like-minded people at the major political event of the new German Reich, the Nuremberg Party Rally (Reichsparteitag). In winter, he met regularly with his friends at a ski hut in Gollinggraben. While there, he always had a great time in the company of good comrades who, like himself, dreamed of Austria joining the German Reich. And that dream was soon to become reality.

* * *

We were surprised at the news that the Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg met with German Chancellor Adolf Hitler at the Obersalzberg on February 12, 1938. It seemed that things were going in the right direction. This meeting was followed by a reorganization of the Austrian Government. Dr. Arthur Seyss-Inquart as a representative of National-Socialists became Minister of Interior and Security Forces, and the military historian Dr. Glaise-Horstenau was appointed as minister without portfolio. Soon, there was a total amnesty. Many political prisoners were released from the district prisons, but also from the notorious prison camps Wöllersdorf and Messendorf.

In the ensuing days, our mountain town of Leoben was adorned with flags. When the Führer's speech was being transmitted by loudspeakers at the main square, the whole population of Leoben assembled there for the three hours the speech lasted. Afterwards, the enthusiastic crowds flocked to a mass rally where about 7000 people gathered. At night there was a huge torchlight procession.

In the following days, there were repeated major rallies which usually ended with further torchlight processions. On the other side, the Patriotic Front (Vaterländisches Front) called for rallies and protest marches, but these were followed by very few. When Schuschnigg saw no way out, he tried to save the sinking ship by setting up a referendum, scheduled for March 13th. His saying in the Tyrol was "Men, it is time!" (Männer, es isch Zeit!)

The situation deteriorated very quickly in Austria and especially in Styria. Graz [Styria's capital] resembled a military camp, and all this looked very dangerous. Machine guns were brought in position against a determined crowd. Very easily might an ill-considered action lead to terrible consequences.

Great tension prevailed in Leoben during these days. From Vienna, the Fatherland Front sent trucks with communists. They raced through the streets with raised fists and threw leaflets which no one gathered any more. After a report leaked out about postponement of the referendum, which was later confirmed by the radio – first timidly, but then in the windows of many houses swastika flags appeared. And if they were not everywhere, this was due to the fact that it was impossible to get sufficient material. Everybody was now in motion, and hurried into the inner city, greeted each other with the German salute. People took to chanting the words: "One people, one Reich, one Führer!" Strangers embraced; there was a jubilant mood and an outbreak of enthusiasm at the the Town Hall as the swastika flag was hoisted there.

Music blared the rousing old Austrian regiment marches and in the evening there rang from a thousand throats the German national anthem and the Horst Wessel Lied. Great was the enthusiasm, but also inner satisfaction of the people when the members of the gendarmerie and the police shared security duties with the SA and SS – all wearing swastika armbands.

Breathless with excitement, we all heard on the radio a proclamation of Dr. Joseph Goebbels announcing the entry of German troops in our country. Also on the radio we heard the solemn declaration by Seyss-Inquart – now the new and last chancellor – that Article 88 of the Paris Peace Treaty was now ineffective and that Austria wished to join the German Reich.

For us boys, a jubilant celebration; one could expect at least a few days off school! First, however, we awaited with extreme tension the coming of German troops. It gave me the same feeling that I always had on Christmas Eve: "Waiting." Yes, such a day would pass away that easy. We were clearly disappointed when at lunch no German troops were yet to be seen. All the more excited were we when a whole series of German planes roared rather low over our city. With a hell of a noise they flew through the narrow Mur Valley (Murtal) and landed, as we learned later, at the airport in Graz Thalerhof.

A group of German JU 86 bombers preparing for landing in Graz Thalerhof

Throughout the day we waited with high anticipation for the reports on the radio and watched out for the coming of the troops. The expected German soldiers seemed to take their time and only late in the evening the first troops arrived. For us young boys it was a huge disappointment when we found out that these were not soldiers but German police units. For us they were traffic police with their well-known Schupo-shakos [police helmets].

We kept waiting until the early hours of the morning, disappointed like most people at that time. Many women came with flowers to greet the marching soldiers, but they waited in vain. The next day, March 13th, when we woke up, many police units had already arrived. There was great jubilation and, in our enthusiasm, we practically attacked the cars of those officers who greeted us just as friendly. We were allowed to climb on the cars and all had only one goal – to put such a shako on – and we did it then much to the delight and fun of the German policemen. The Austrian police were still in the Austrian uniforms, but already had the swastika armbands and they shook hands cordially with their German colleagues.

German Police were the first troops to come to Leoben

Willy's schoolfriends were allowed in police vehicle wearing "shakos"

These days, the melting water rose to such levels in the Mur, that there were several floods and the Wasen bridge and the wooden bridge in Judendorf were threatened.

Our enthusiasm had no limits. We felt very happy – we were free! All this we owed to one man, "the Führer." And we believed with conviction in this exemplary figure. The newspapers were full of Hitler's sayings, pictures were everywhere – on the streets, in the shops. The Führer was everywhere. And we loved and trusted him. It could even be said – "blindly."

We young boys waited longingly for the moment when we should get the, for us, so impressive uniforms. We had only recently become Jungvolk and were called "Pimpfe." (Much later I learned that the word "Pimpf" originates from pumpernickel.) This was because we wore the black velvet pants, a black scarf, like a tie, drawn together at the neck with a leather-knot and also a wide black leather belt with a plaque and the symbol of “Pimpfe” on it. But our pride was the hunting knife, which was worn like a bayonet on the side. And the head was adorned with a black cap, also provided with the HJ badge in front. Yes, and like all Nazi organizations we wore an armband with the swastika. We had to wait and watch jealously as others got those desired uniforms before us.

The three Wenger men in uniform. I as a “Pimpf.” Dad as a Technical Emergency man. Poldi as Gefolgschaftsführer [cadre unit leader] of the Hitler Youth.

Category

Adolf Hitler, Germany, National SocialismWilly Wenger's Family Chronicle

- 4618 reads

The following is the continuation of the family history written by Willy Wenger that first appeared on March 14 under the title “the great hope: the German Reich.” Wenger was born in 1926 in Styria in the diminished independent nation of Austria, 'victim' of the Paris Peace Conference following WWI. Willy had a loving father and mother, and an older brother Leopold (named after their father) with whom he was very close. From the time Leopold Jr. first began to speak, he was called “Bibi” (a mispronounciation of Bubi by the child), a nickname that took hold with family and friends all the way through high school and beyond.

The Referendum of April 10th, 1938

By Willy Wenger

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Willy, Gretl and their mother standing in front of their apartment building on Referendum Day.

Several months ago we had moved from the Timmerdorfer-Straße to Dreierschützenstraße No.16 where we had a larger apartment that belonged to the municipality. It consisted of a kitchen, a pantry, a small room – a cabinet, as we call it in Austria – with two beds, and a spacious loggia opening on a large garden in the inner part of the massive block. There was also a large living room, and the parents bedroom, as well as a hall and the toilet. Gretl slept in a small bed in the parents' bedroom, while Bibi and I shared the cabinet. Our building accommodated the municipal baths, which had bath tubs and showers which we used frequently.

Election Day was Sunday, April 10, 1938, on Dad's 45th birthday. Many had predicted that the referendum would be a big success for the N-S regime, and with the end result, all doubts were gone: the people decided and the result was convincing. Never in history has there been such a clear result: In Leoben, the vote was 99.83 per cent in favor – the proof of the willingness of the Ostmark to join the German Reich.

This result may be difficult to understand today, after so many decades have passed; especially the youth of today can hardly imagine the situation at that time. For us old folks, it's understandable. Our generation was not one bit dumber, but the time was totally different and the votes in favor of the referendum show the strength of the faith of millions, and our idealism.

The Grand Hotel and other public buildings in Leoben decorated for the referendum.

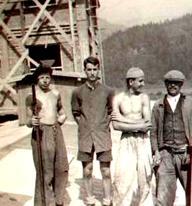

Left: The employees of Lenhardt & Co. (including Leopold Wenger Sr. third from left) demonstrate their approval for the unification (Anschluss) in front of the company office.

May 1st was also celebrated as never before. "Work ennobles" was the saying from now on. The various companies organized outings, usually with the traditional raising of the Maypole. Dad went with the entire staff of the branch of his company, Lenhardt & Co., to Bruck where they celebrated with other colleagues at the company's headquarters. It's interesting to look at these pictures today. Almost everyone wears a hat, unlike now. Of course, the May Day was dominated by the new regime: swastika flags were everywhere.

On the first of May, according to the old tradition, a fertility Maypole is raised. The ancient custom remained strong in our area, but is also maintained in some areas of Germany. According to ancient tradition, a young spruce, at least 30 meters in height, is cut down in the morning hours of the 30th April. After the so-called "Schäpsen" (removal of the branches ), the tree must be "geschäpst" (debarked) according to tradition, so the evil spirits and witches cannot hide under the bark, dressed as beetles. The green top of the tree is preserved because, according to tradition, that is where the gods live. Wreaths symbolize the female element which is penetrated by the male element, the stem. The top of the maypole is decorated with colorful ribbons.

Mayday 1938 company celebraton at A. Lendhardt & Co.

In some areas, figures representing artisans and farmers are placed at the top, too. Robust youths watch over it during the night to prevent theft of the tree by young people from the neighboring villages. On May 1st the tree is slowly raised up and secured with the help of long poles, which can sometimes take up to two hours. The tradition forbids the use of technical equipment for raising the Maypole. In some places, full bottles of wine are attached to the wreath and the stem is smeared with soft soap to impede climbing the trunk by bold fellows.

But this time the celebrations of the 1st of May also became a meeting of various National Socialist organizations, with parades and a lot of march music, in which all the people participated with excitement. But above all, there was a lot of dancing. The boys and girls wore their gorgeous costumes which gave the popular dance “Bandeltanz” an especially attractive, colorful appearance.

For the youth, tent camping was great fun

During the holidays, we went to the tent camp. It was great fun; we all loved the camp life. Once, we were at the famous Green Lake where I with the “Pimpfen” set up camp on a stream that flowed out directly from the icy green lake near Tragöß. The lake is emerald green and swells after snow-melt to several meters. The water was clear and clean, but … bitterly cold! And yet, we tried to harden ourselves and swam a short distance in the terribly icy waters. We cooked for ourselves and in the adjacent forest there were many games and competitions.

Grünen See, Styria's emerald-colored frigid-water lake

Another time we took part in a major annual gathering of Upper Styrian Hitler Youth at St. Michael. Their camp had new, large round white tents. Early in the morning there was a roll call and the camp flag was solemnly hoisted, accompanied by fanfares and drums. The young people always had a lot of black flags with the symbol of the “Pimpfe,” while the older boys had large banners with the emblem of Hitler Youth. Every group (Gefolgschaft) had their own drums and fanfares which gave their entry into the camp a solemn character. In the evening there was usually campfire; we crowded around it, singing happy songs. We all had a great time and regretted when it was time to leave these adventurous camps.

St. Michael Upper Styrian Hitler Youth campground, an annual event

"Every group (Gefolgschaft) had their own drums and fanfares which gave their entry into the camp a solemn character."

"Early in the morning there was a roll call and the camp flag was solemnly hoisted, accompanied by fanfares and drums."

We have all grown together into a single community and talked a lot with each other. Even at school, we now had a much closer relationship both with our classmates and the superiors, the entire faculty. One no longer had the feeling of suppression. We could understand one another and enjoy ourselves with the teachers, while still respecting each other. Due to the fact that we now had girls in the class, we were less rowdy.

In the fall, we now and then got a few days off from school, sent by the H-J to help the farmers bring in the harvest – and do other necessary work in the barn or in the field – everywhere we helped with great zeal. It was always pleasant work, and afterward the farmer served a powerful, nutritious meal that we were always excited about in advance.

Life at home amid a patriotic population

As already mentioned, we lived in the Dreierschützenstraße, named after the soldiers of the Mountain Infantry Regiment, which was located just a few doors from us in the Leobner barracks. I liked to observe them at drills. These Alpine troops had smaller horses, pack animals that carried gun barrels on their sides, and wheels for the guns and ammunition boxes. I distinctly remember an incident that has remained in my memory. One of the soldiers was kicked by a horse in the lower abdomen. He was obediently signed off by his superior before he lost consciousness and fell down. That gave me a respect for horses. Ever since, I have always made a big circle around these animals.

Our building bordered on a very large corner house where the district headquarters of the NSDAP in the district of Leoben had its head office. Before the Anschluss it had been the seat of the Austrian Fatherland Front. Now, there was more lively activity there which we watched from the living room window. From here we also saw the square in front of the church and the railway bridge which spanned the river Mur flowing near-by, and the railway station.

One day my school colleague Helmut Terlep told me: "Your mother is going to have a baby." He had recognized it through her waist circumference (he later became a doctor). I had not known it nor noticed. But there is a history to it. Adolf Hitler had some time earlier stressed in a speech that a German family must have at least four children. And these words appear to have been taken very seriously by many people. I knew a few families who had not had children for several years and now, suddenly, came the "laggards" into the world in 1939. The same happened at the Holzers. Our youngest brother, Wolfgang Gerhard, was also born in 1939.

Bibi was quite engaged in the Hitler Youth. He had many friends from the illegal time, with whom he spent happy hours. In the meantime he had become Gefolgschaftsführer, bringing with it more commitments. He also visited several camps, especially during the school holidays. Dad took me very often on bicycle tours around the Leoben area. He had a small seat on the handlebars, so that Gretl could always accompany us. Mom preferred to stay at home. In the fall, Bibi traveled, this time by train, to the NSDAP Rally at Nuremberg which he had visited by bicycle in the previous year as an illegal Hitler Youth. This time, his friend Gilbert, who was a party member, went with him.

We are three good friends: Bibi, Gretl and Willy

Like Bibi, Dad was always busy as a political leader in the local party organization of Leoben. He had to supervise the entire block in which we lived. Besides, he had, like many businessmen, also registered for technical self-defense and assisted with their missions. The Technical Emergency (TN) was a kind of voluntary firefighting organization. The men joined together in emergencies, catastrophes, supported the firefighters and helped the farmers where it was necessary. In Leoben, the TN had two motor vehicles: a truck and a terrain car, similar to the later "Haflinger," only bigger. It was an event when Dad, who was the driver of the off-roader, brought this vehicle to the garage located in a courtyard in the Gösserstrasse. He had to drive about 10 steps up, which in the middle of the city was not fun. Dad had to collect the modern vehicle in central Germany, so it was fortunate that he had gotten a driving license some years previous at the company where he now had a senior position. He only had to take an additional test for off-road driving.

Dad is 3rd on the right of the Technical Emergency (TN) volunteers for quick assistance, and the driver of the small terrain vehicle at left, both owned by the TN.

Leopold Wenger Sr. stands in the center of the local political group in 1938

1939 and the Napola School

The political situation deteriorated in the course of 1939

In the New Year we had a lot to learn in school. Along with Latin we had to cram also for English. Our professor was a younger man, Mr. Molterer, whom we also had for sports lessons. It was a time when our behavior was quite boisterous. Once, some classmates had smeared the sliding chalkboard at the edges with curd cheese that smelled quite strongly ... Prof. Molterer took it in a stride and said that when he was in high school they had played much worse jokes. Of course, this was the reason that some of the rascals brought a few stink bombs into the classroom and the stench was really brutal. As a consequence, we had to stay behind.

Another time, one had placed a piece of wood on the top edge of the classroom door. Of course, it hit our class teacher, Pessl, directly in the head and again it meant detention. We had another teacher who, at the beginning of class, quick as lightning tore open the door and literally rushed in. We clowns lifted the door off its hinges and left it leaning. When he grabbed the door to come in, the door fell with a loud bang and the "urgent teacher" stood with both feet on the classroom door.

Bibi's best friend, Gilbert Geisendorfer, also a Gefolgschaftsführer in H-J at this time, showed Bibi an ad in the Styrian Tagespost in which a German national educational institution in Pomerania was appealing to young Ostmark boys. The advertisement invited the boys to report for an entrance exam in Berlin. The two comrades deliberated and said, "We will present ourselves, and if we fail the test, well, then at least we have seen the capital.” Thus said and done, they sent in their applications, went to Berlin, passed the entrance exams and stayed in the old German Reich. In this way did they come to the Napola. It was a National Socialist educational institution, but kind of a secret military academy for the training of Air Force officers.

On June 10, 1939 my brother Gerhard saw the light of day in the hospital of the miners in Seegraben. Now we were a real German family – reason enough for Mutti to get a Mother's Cross (shown right).

We celebrate the naming of Gerhard: Standing from left: Father, Mrs. Baschlberger, Bibi, Willy, Uncle Emil. Seated: Mother with Gerhard and Gretl.

Now, the roles were reversed again: Gerhard was in the center around which everything in the family revolved. Bibi learned of this birth in Köslin and was very happy to have a new little brother, as he expressed in his letters again and again. Finally, he was able to come during the summer holidays to Leoben for the official naming ceremony (instead of a baptism). Gerhard got a second first name, Adolf, to honor the instigator of his existence.

On June 27, 1939 Bibi went with his classmates, the so-called Jungmänner (young men), to a glider course in Rositten on the Curonian Spit in East Prussia. On this 98 km-long peninsula with high sand dunes, next to a world-famous bird observatory, is a Reich-gliding school. The route of the railway there led through the Polish Corridor, which stood for some time at the focal point of political dispute between Poland and the German Reich, and should be recognized as one of the causes of the outbreak of World War II. At Danzig, they crossed the border. The cars were locked, but the uniforms of the Hitler Youth with the swastika bands often aroused displeasure in the Polish workers along the railway line. In their arrogance, the young chaps certainly provoked the Poles by displaying their armbands from the car windows. And the Poles took turns threatening, cursing loudly and waving their fists in the air.

The weeks in Rositten were very nice. They had to pass the "B-test" for gliders. The aircraft SG 38 and Grunau Baby were pulled by a motorized winch to the necessary altitude and flight students learned to fly curves, circles and eights. Bibi reported that for the first time he was able to see moose that live there in the wild – from the air. The beaches were gorgeous, with their high sand dunes. In their spare time they went on searches for the yellow amber, and Bibi brought us some small pebbles. The trip back through the corridor was similar to the journey there. Just eight weeks later the Second World War began here. Bibi then spent several weeks in Leoben. But still wanting to get some spare change, he wanted to work and Dad took him into his company as a roofing worker, which was probably hard labor, but at least it gave him a little extra money which he could always use.

Bibi chooses to work for Dad as a laborer during school holiday, in full summer heat.

In late August Bibi returned to Köslin and was now in the graduating class. We often got his letters and I found it always of great interest to read his reports. After the glider stage he needed, like all these young men, to get a driver's license for motorcycles and cars. For this purpose they took a course in a Pomeranian town (Dramburg). I was very impressed by all this. At that time, the only connection we had was by the mail. We could communicate only through letters; almost no private person had a telephone. For birthdays, we sent and received congratulations by telegram. Thus, we were forced to exercise patience.

In the floodplain near Leoben we held our evenings for the Jungvolk, and here we had our parade ground. Once, one of the Hitler Youth leaders asked me to take over the leadership of a youth group. Under his oversight, I had to command, "Stand still,” then "dismissed," then "to the left or right, look to the left", etc. I felt like an artist who is teaching his puppets to dance. As the whole team had to do it in unison, everything suddenly seemed so unnatural. It seemed so funny that I laughed after each command because the young men were dancing to my tune. I think I must have made a very ridiculous figure. I don't seem to have been created to be a tamer of a youth squad.

We followed the conference in Munich in the newsreels at the cinema. We saw the pictures of the entry of the German troops in the Sudetenland, of the occupation of Czechoslovakia, of the declaration of a German protectorate and we were thrilled that our Führer united these countries into the Greater German Reich. We were convinced that Danzig also had to be occupied. All the former territories which had been taken by the Treaty of Versailles from the German Reich were again being united. All these occupations were widely welcomed, especially as it went without bloodshed. Now we wanted East Prussia, which was like an island separated from the Reich, to be at least connected with the mainland by a corridor, which of course was met with violent resistance in Poland.

The situation became precarious and ultimately led to the start of World War II. Hitler pushed into Poland on the 1st of September 1939. Just two days later, on 3rd September, Britain declared war on the German Reich and France joined in ... and not vice versa, as is often falsely said. The war was actually forced on the German people, which many often do not want to admit today. So stupid not even Hitler could be to want to engage in a two-front war. On the contrary, he tried all means to keep the Allies, especially England, out of the war. In the back of his mind he was already thinking about the crackdown on and destruction of Bolshevism, and an expansion of the German Reich in the East (after Germany was deprived by the Treaty of Versailles of all its colonies).

Hitler was aware that the German Reich never would recover these colonies. But he always flirted with the idea of expanding the German Reich to the east. The war with Poland probably seemed a welcome opportunity to carry out his plans. And subsequently, he expected to destroy Bolshevism quickly. But he wanted by all means to prevent war with the Western powers Britain and France – definitely not to engage in a war on two fronts, which for a logical thinker should be understandable.

Therefore, the surprising declaration of war by the British and French governments on 3 September 1939 met with incomprehension, because all the previous diplomatic negotiations suggested rather an understanding of the Western powers, especially of Britain, with Germany. One need only read about the agreement at a conference in Munich, where Chamberlain expressed loudly his enthusiasm for Germany and Hitler and then proudly presented the agreement to the world. It is now known that Hitler had a friendly correspondence with the Duke of Windsor, the abdicated former British king. As late as August 1939, the Swedish industrialist B. Dahlerus, a personal friend of Hermann Göring, made several trips to London to negotiate with the British government to smooth the exchange of views and enable the rapprochement to the German Reich. It was widely known that Rudolf Hess had an English wife and thus excellent relations to the English aristocracy. Therefore, the German people could not understand the declaration of war by the British Government.

The Second World War has, contrary to all promises of "no more war,” broken out!

Category

Adolf Hitler, European History, Germany, National Socialism, World War IIThe Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

- 5234 reads

Exclusive at carolynyeager.net! This is the never-before-published true story of a young German soldier thrown into the battle of Seelow Heights in the last month of the Second World War—how he survived against all odds and managed to return home.

The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

From the Seelow Heights—April 1945

Back Home to Leoben, Austria—July 1945

By Willy Wenger

An officer-candidate in the German Luftwaffe, Willy Wenger was only 18 in 1945 when his “odyssey” began. He is now 86. His older brother Leopold Wenger was awarded the Knight’s Cross, Germany's highest military decoration.

Translation and Introduction by Wilhelm Kriessmann

Editing by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

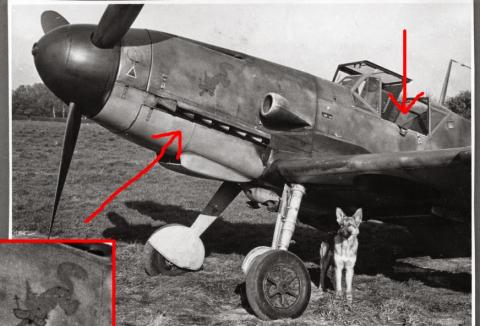

For the 17-year-old high school student Willy Wenger, his brother "Poldi," squadron leader at SG10 of the German Luftwaffe, was an outstanding role model. Willy wanted to follow in the footsteps of this highly decorated Jabo* pilot, who was five years older than himself. In July 1942, Willy received his C license for glider pilots (pictured at right on glider) and in April 1943 at the Reichssegelflugschule Spitzerberg near Vienna, he earned the Luftfahrerschein (air pilot pass). (See picture below)

[*Jagdbomber: fighter-bomber ]

The war situation in the spring of 1943 made it necessary to call up the final classes of high school students to the services of the Home Anti-Aircraft Forces, or FLAK. Wenger’s high school class assembled at barracks within the steel plant of the Herman Goering Werke (later named Voest-Alpine) at Linz/Donau. School lessons continued but the young pupils also had to learn how to handle the 3.7cm anti-aircraft guns and all the additional equipment.

Above: Wenger earns his basic pilot's license in 1943 at the flying school at Spitzerberg.

Because of injuries at gun practices, Willy was able to spend a furlough at home in Leoben at the same time his older brother Leopold, the Luftwaffen pilot, also arrived back home for a short leave.

Turbulent months followed his return from his New Year furlough to his FLAK unit in Linz. Only a few weeks after the class returned to the school in Maburg and report cards were issued, Wenger was called to the service at the RAD (Reichs Arbeits Dienst), Reichs Labor Service, an obligatory three-month draft. During the three very cold winter months of 1944, the RAD men were working on a railway ramp to connect the main line with a trunk line to a large armament plant in Silesia. Basic boot camp training was still part of their activities, however. (Right: Willy is in center of group) In early May, Wenger was back at school in his last year but, as it turned out, only for a few weeks. There were merry reunions, parties and dancing and when the call for military service came, Wenger volunteered to be an officer candidate in the Luftwaffe.

On July 6, 1944, he arrived at the Kriegsschule 3 at Oschatz, in the state of Saxonia. As a Fahnenjunker (cadet), he was looking forward to becoming a pilot like his brother.

That dream ended when Reichsmarschall Göring ordered 100,000 Luftwaffen personnel to fill the gaps suffered by the German army. In early spring 1945 Fahnenjunker Wenger, now Fallschirmjaeger (parachute trooper), was on the way to the Eastern front some 80km distance from Berlin.

We now let him tell his story:

I was literally thrown out of the luggage netting where I had just found space to take a nap. A screeching, breaking noise and then a sudden stop. Mixed into it was the terrible howling sound of numerous sirens - horror music like a multiple echo swept across the area. Though experienced by the civilian population for years, it had luckily been unknown to me up until now. It was late March 1945 when we entered Berlin by train.

I had never experienced any air attacks before. Not in Marburg, where I attended high school in the summer of 1943 and lived with Aunt Hilda in her big house. As soon as I left, a bomb hit the house and demolished part of it. Straight from the high school in Marburg we were drafted into the Flak. In Linz, we Hitler Youth became anti-aircraft gunners.

I arrived with a train transport at a location close to Berlin where we had to run away from the train because all hell broke loose. Sirens were howling gruesomely from all directions, accompanied by the engine noise of hundreds of bomber airplanes approaching the city. Searchlights cast their rays into the sky and caught an aircraft from time to time. Soon darkness turned into bright light as burning "Christmas trees" floated from the sky, marking the targets. They were dropped by the enemy pathfinder airplanes.

I ran into a field and tried to dig a protective hole into the frozen soil with my empty canteen but without much success. When scared to death, one develops super strength. Then the bombs dropped like a carpet over the city, some close to us. We jumped up and down thinking to be torn to pieces any minute; the pressure of the explosions seems to destroy the eardrums.

Even though the attack lasted only minutes it felt like an eternity. Then, as the engine noise simmered away and only sporadic anti-aircraft gun fire occurred, one could see the ghostly remains of the vast housing complexes lit by an immense blaze. I never imagined my first encounter with the capital of the Reich would be like this!

Finally, our train arrived at the railway station of a suburb. Something very touching happened. One of our comrades noticed his mother on an arriving train. He waved and yelled; his mother came over, stayed with him a few hours and drove with us to the next station where she departed with tears in her eyes.

Well, here I was now, a Fallschirmjaeger wearing that odd, coat-like, long uniform jacket and the special helmet – so different from the infantry helmets – with flattened edges to avoid air resistance when jumping. The Inside was cushioned with heavy rubber pads. A parachute, however, I did not carry.

As a glider pilot at the Reichssegelfliegerschule Spitzerberg I always carried a parachute but never used it; never jumped. Only much later, in 1977 in North Africa, I jumped out of curiosity and hurt one of my vertebrae. As a result, I still have trouble turning my head properly.

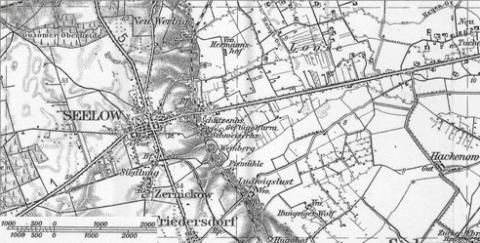

I did not know which city parts of Berlin we marched through but the general direction was North. They said Stettin was our target . We took our first rest at a very idyllic recreation spot, a forest next to a lake in the vicinity of the city of Finsterwalde. I remember the place because I mailed a parcel from there to my parents. They never got it. We drove towards Angermuende and received the order to turn southward, parallel to the Oder river, until we reached a small village, Seelow, west of Kuestrin. There we disembarked.

The Seelow Heights overlook the Oderbruch, the western flood plain of the Oder River which is a further 20km to the east.

Near a small farmhouse, we occupied an already pre-built large trench system. I was now a member of a Sturm-Zug (attack troop) at a parachute troop unit. All of us were youngsters, none over 25 years old. Our troop leader, a young lieutenant just a few years older than us but already an old timer, told us that we had been selected to attack the enemy even if all others retreat. We were kind of proud to hear this.

At the corner of the farm house I saw a row of shoes covered by canvas, with only the toes protruding. A soldier explained they were dead German soldiers, killed last night when they tried to break out of a Russian encirclement and were hit by our own artillery which thought the Russians were attacking. Never before had I seen a dead person and was afraid to look at death, and did not therefore help to put them to rest.

At this time of the year it was still very cold and at night we were really near freezing. I had to share a small foxhole with my comrade. This was our living quarter where we stored our belongings and weapons and where we slept. Pressed together, we lay there on straw, protected on top by two logs covered with soil … pretty crummy.

Now I was a combat soldier, fulfilling my duty, holding the attack rifle in my hands and carrying the hand grenades around my hip, trotting through the wide system of trenches and being mighty proud. Even as the first artillery shells hit closer it was an adventurous happening. But when the shells hit closer and closer, my heroism disappeared rather fast and I anxiously ran for cover. I was terribly scared.

We crouched in the trenches and waited and waited – sometimes the Russian artillery decked us pretty good. The first wounded yelled, the first blood ran, and I was afraid I would lose consciousness. I tried to hold on to something but then realized I had to help and I regained strength and was not afraid. That Will helped me for the rest of the war, never again did I collapse.

At the East bank of the Oder River the Russians had concentrated strong forces close to the damaged bridges during the last few days, ready for the crossing. We saw several Ju 88 bombers, protected by fighter planes, flying over our trenches. Mounted on top of their wings were FW 190 fighter planes steering the 88's loaded with detonation material into a steep dive down onto the Russian concentration. [Willy was seeing the "Mistel" composite aircraft, pictured at left. The name came from the German "Mistletoe." It was also called Beethoven's Device and Daddy and Son.-cy]

All hell broke out, the Russian flak fired out of all their barrels, we could see red flaming grenades flying into the sky (we called it the tomato flak). Black clouds formed by the exploding shells crowded the sky. When the heavy bomber planes hit the ground the strong Russian anti-aircraft defense was suddenly silenced. Heavy smoke columns raised skywards. Shortly before the attack, Hermann Goering, the Reichsmarschall, passed by our trenches to watch the air attack of his Luftwaffen pilots.

For quite a while after these Luftwaffen attacks our front line was rather calm. We all knew it was the silence before the storm. Our daily food supply got worse – an old soldier delivered it on a broken down carriage drawn by an old, half starved horse. It consisted mainly of bread and milk, over-cooked potatoes, and pudding powder without any sugar. The so-called cook had no idea what he was doing; he was holding the job in order to avoid Front service. When he was supposed to bake bread with flour, which he said he found at a desolated farm house, it was gypsum powder that he mixed. That's what we had to live on.

There was not much shooting going on. Everyday Russian reconnaissance airplanes circled above our front line dropping leaflets asking us to surrender. The air traffic increased at night when a small airplane – its engine sounded like a sawing machine – dropped bombs which missed but the noise kept us awake. Sleep was very light and rare, we all were under severe tension. The Russians succeeded in crossing the Oder River at Kuestrin and had a bridgehead at the Western bank. Masses of troops flooded the area with tanks and artillery.

In the early hours of April 16, 1945, a massive 2200 cannon artillery barrage began and literally tossed every square meter of the German defense line.

Devastating was the howling noise of the Russian rocket artillery, the Stalin Organs (pictured above). You could hear the regular artillery shells buzzing in but the rockets hit like a sudden lightning. This heavy barrage lasted nearly three hours. Russian airplanes dropped their bomb carpets on our defenses. Finally at 6:55 the Soviet infantry attacked. Horizontal searchlights ghostily illuminated the battlefield, blinding friend and foe; dense fog increased the turbulence. Total chaos reigned.

We could hear but not see the fearsome rattling noise of thousands of Russian tank wheel-chains and, likewise, could only hear the echo of the gruesome yells of the storming Russian infantry. We were scared to death. The moment arrived when we wanted to leave and run away from our trenches but it turned out that we ran in circles. We lost our orientation completely and arrived at a small bridge which we had seen only shortly before. We were running in the midst of Russian infantry and tanks that were visible only as shadows – a total confusion. The time between the artillery barrage and the attack seemed like eternity.

The anxiety one experiences in such a situation is indescribable. Closely pressed to each other, my comrade and I lay in the foxhole and felt the slightest shivering of our bodies. We started to pray and expected to be hit any moment and were then surprised to still be alive. By that bombardment of shells and rockets not one inch of the terrain remained untouched. Thank God we did not stay at the same spot but ran panicky for coverage.

After running around for several hours I found my platoon leader, the young lieutenant. He also looked rather distraught and felt sorry that we inexperienced soldiers had to go through such a traumatic experience. Most of our comrades we could not find. They probably did not survive the vehement Russian attack. I found out that my foxhole neighbor was seriously wounded and lost an eye.

We had to retreat westward. On the way we ran into a SS unit; they ordered us to counter attack. We were bunched together, no one knew each other but we moved forward – such a diverse unit – and all of a sudden found ourselves marching through dense fog between Russian forces. Desperate, we dug ourselves in on top of a small hill. All was frighteningly quiet around us. We were exhausted and dog tired.

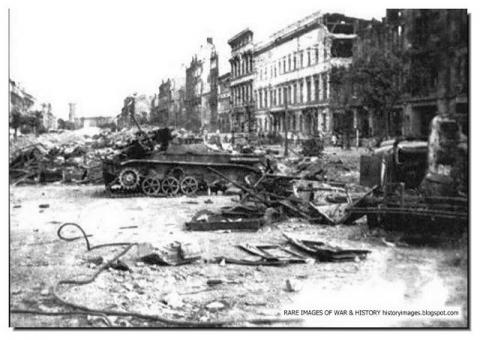

That was the moment for us to beat back the enemy. We started our counterattack and stormed forward. Horrible was the smell of burned human flesh in the destroyed tanks as we closed in. Tremendous smoke clouds rose into the sky, shrieking battle noise all around, and the thousand-fold “hurraehh” roar of the attacking Russians. It was hell!

Right in front of me a Russian soldier suddenly sprang out of a bush, his rifle directed at me. It was the only time in my life that I was forced to aim and shoot at a human being in order to save my life. I certainly had my jitters and trembled. The Russian probably also. Both shots discharged nearly at the same time, both missed and we both ran in opposite directions into protective bushes. I still remember very well that I lost the reserve bullet magazine of my assault rifle, ran back and picked it up. Afterward I thought how dumb I was to run back and expose myself to the enemy. They could have killed me.

We retreated again, better said, we ran to save our lives – behind us the gigantic mass of attacking Russians. It is impossible to describe the situation. We reached Muencheberg. I always remember the event there. During a short pause in the fighting I ran into some comrades who were separated from our unit. I was very angry about the SS fellows ordering us to that senseless attack while they retreated. I turned pale when, turning around, I looked into the eyes of a tall SS man in uniform. But he agreed, and joined us and stayed with us all the way through the final Berlin battle. He was a Berliner and a very reliable comrade.

Chaos and confusion all around. One could not find his comrades anymore. From time to time we were controlled by the military police, called “chain dogs” (Kettenhunde) because they wore a small metal shield on a chain around their neck. They were looking for deserters or stray soldiers, thus not too popular with the common soldier.

On April 20, 1945, Adolf's 56th birthday, one of the fellows said "Today Adolf is celebrating his last birthday," a remark he would not have dared make a few weeks earlier. At a shelter in the woods we listened to Dr. Goebbels’ speech, calming and inspiring us, about new miracle weapons that would reinforce our forces. We had no idea what was happening; what the situation was. We did not know that the American Army was already deep into Germany and approaching from southwest of Berlin. New hope bubbled up. But ten days later Hitler was dead and the Third Reich destroyed.

* * *

When the Russian offensive began, Marshal Zhukov addressed his troops:

"Soviet soldiers, take revenge in a way that the invasion of our armies is remembered not only by the present German generation but by their descendants in the distant future. Remember also that everything the German sub-humans owned belongs to you. Soviet soldier, have no mercy in your heart."

Every German soldier now had to face such slogans. He was thinking about the uncertain future—what will happen? Apathy took over and the only thought became survival. Gone was our idealism, our belief in the just cause, and our enthusiasm – but still we wanted to defend our homeland. In panic, everyone moved westward – masses of soldiers but also civilian refugees, women and children moved through the Brandenburg landscape. By foot or with horse-drawn wagons or pushing their own carriages, while behind, the thunder of guns in between shell explosions, detonations, smoke, dust and the approaching shrill “hurraehh” of the Soviet infantry.

We gathered again on top of a hill, a group of stray soldiers which my lieutenant and I ordered into trenches to set up a defense line. We were both surveying the area when all of a sudden whistling shells exploded around us . A Russian rocket hit. I heard the cry of the lieutenant, "Wenger, I got hit, help please."

We were close to a farmhouse and I was able to find a two-wheel carriage upon which I loaded the wounded man and pushed and pulled, as it seems for hours, until I reached a field emergency hospital. Hundreds of wounded German soldiers were being treated, most laying on the bare ground, and the doctors operating on tables in the open air. A pitiful scene, filled with blood and misery. They clung to my arms and legs and cried out for help but I had to march on with the troop of lost soldiers westward towards Berlin.

Shortly before Koepenick we were lucky again when a series of Russian artillery shells hit a mighty tree on a hillside where we had intended to rest, but moved away when I warned my comrades. I am not superstitious but when I found a horseshoe on the first day of the Russian offensive, and looked for one and found it everyday from then on, I considered it my lucky charm. At Neukoelln, we reached the city edge of Berlin. Tired as we were, we dragged ourselves through the empty streets towards the railway station, just in time to meet an arriving food supply train. We received our special rations, and, in addition, I got a big margarine cube which a little later I gave away to a young woman with her child.

We were now in the capital of the Reich at its eastern part, ruins and rubble all around – apartment caves, barricaded windows, stove pipes like black fingers sticking out into the cold air. When we marched through Koepenick I smiled bitterly, remembering the comedy of the “Hauptmann (Captain) of Koepenick.”

It was dark when we reached the Teltower canal and entered a factory hall full of iron ingots and half-fabricated tools to find our night quarters. There we established our new defense line and I, an 18-year old youngster, was now in charge of a platoon of members of the Volkssturm (people's militia); most of the men could have been my grandfathers. They asked me awkward questions, like 'how to handle a Panzerfaust?' (bazooka) which I had never handled myself. It was very hard for me to keep their confidence.

Late in the evening a small troop returned from a reconnaissance tour loaded with cartons of chocolate. Across the Teltower canal they had found the well-known Sarotti chocolate factory, completely desolated, and took whatever they could carry. The Russians were already close to the Tempelhof airfield.

It was pitch dark when I stepped out to investigate our immediate neighborhood, finally having a chance to munch on my provisions. As I cautiously approached a bridge that I wanted to cross, with the thundering sound of Russian artillery bombarding Tempelhof, a tremendous blast suddenly occurred. My little food parcel flew into the air, I lost the bite I had just taken and struggled to the ground. The bridge was not there anymore; German pioneers had set the explosives. Shattered, I returned to the factory and now helped myself to the Sarotti chocolate; the biting hunger was soon gone.

A young NCO from Vienna who had joined our troop always walked around with his automatic MP slung around his shoulder and the unavoidable happened. He tripped, his gun hit the hard floor, a shot discharged and hit him in the stomach. The poor fellow yelled, roared like an animal, beat with hands and legs around him. I can still hear the terror cries, but don't know if he survived.

We move on toward the center of the city, the Russians close behind us. We were told to take whatever we can from the warehouses before the Russians arrive. So, whole butter barrels were dropped from the Karhaus department store. Never in my life had I had such thick butter sandwiches. On the way we found our SS man again; he had gotten lost and was involved in some street fighting. His head was so wrapped in bandages he looked like an Indian. A Russian prisoner carried his ammunition belts and together we marched and reached the S station Gesundbrunnen and the Humboldt Hainpark.

Two giant flak towers loomed into the sky – one of them became our new quarter. Finally, we could rest on mattresses and soon fell into deep sleep. The Russian prisoner tried to run away, was shot and buried right there. (Right: View of the Humboldthain Flak Towers in Berlin as they stand today.)

We spent about two days in the bunker, exhausted, losing any contact with the outside world. No gunfire, no smoke, no roaring . The thick cement wall kept everything away. But it was quietness before the storm. We marched out and were surprised by a heavy air raid – the sirens did not work any more. I ran into the cellar of an apartment house when the bombs hit. Walls and ceilings tumbled down, dust, smoke and darkness surrounded me. I was buried and lost the orientation but could hear muffled yells. Digging and crawling I finally found an opening excavated from outside. What a relief! Dusty and dirty and blue spots all over but otherwise okay – I survived.

Again we were astray, our unit did not exist anymore and we were directed to gather at the Maikaefer-kaserne (barracks) at the Chauseestrasse, the battle post of our parachute division. We arrived and bivouacked at its spread-out grounds. Pretty soon an alarm came; a police officer reported the approach of a Russian tank and requested volunteers for a counterattack with Panzerfaust Bazooka (Picture below left, a volksturm man with a panzerfaust). I thought I had to join even though I had no idea how to handle a Panzerfaust and, sure enough, I nearly killed myself when I tried to discharge it with my back close to a stone wall.

The officer called me back. We crawled across a yard into a small house and were supposed to occupy a better position in the nearby building block. I considered that plan insane but had to follow orders. Under heavy Russian MG fire from three sides, we had to storm the house, now positioned between the two front lines. Behind us the German Police unit protected us with their gunfire, in front of us the Russians shot at us wildly.

From the cellar of the house a few women ran towards us, threw their arms around our neck, kissed and cried and demanded that we enter the cellar to witness some horrible crimes. I tried hard to avoid that; the Russians could throw a hand grenade into the cellar and all of us would have been killed. The Russians were only a few meters away, shooting like crazy and throwing hand grenades. They wanted to retake the house. I covered from behind the front door and when I dared for a quick look out, sure enough I got hit.

A fiery flash, a strong detonation, I felt something strike my hand and immediately blood ran profusely. A Russian hand grenade exploded close to the door.

To be continued. End of part one.

Category

Germany, Willy Wenger, World War IIThe Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger (Part Two)

- 5097 reads

The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

Part Two - Conclusion

From the Seelow Heights—April 1945

Back Home to Leoben, Austria—July 1945

By Willy Wenger

An officer-candidate in the German Luftwaffe, Willy Wenger was only 18 in 1945 when his “odyssey” began. He is now 86. His older brother Leopold Wenger was awarded the Knight’s Cross, Germany's highest military decoration.

Translation and Introduction by Wilhelm Kriessmann

Editing by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

From April 20th onward - the final days of the Reich - 18 year old Willy Wenger was involved in the Battle for Berlin. His story continues right after receiving his first wound as he covered for German civilians trapped inside the cellar of a house. As he attempted a peek out the front door to check conditions, a Russian grenade exploded close to it. A grenade fragment struck his hand, bringing forth profuse bleeding.

For the time being we escaped hell; it was insanity what we tried to accomplish near the Sparre Platz next to a waterfront. (I still carry the grenade fragment in the ball of my left hand. I feel it only when I hit something accidentally.) We marched back to the Maikaefer barracks.

The long row of barracks on Chausseestrassee as it appeared in 1910.

I was sent to a first aid station to get properly bandaged and to receive a tetanus shot. Marching on, I was informed that it was the famous Hotel Adlon on the Unter den Linden, close to the Brandenburg Gate, where I could get help. With ruins and wreckage all around, I tried first to cross the wide Unter den Linden avenue – impossible with continual rocket fire from the Stalin Organ batteries. So I found the subway entrance and finally entered the Adlon, my first encounter with my future profession.

The luxury hotel Adlon after the Battle of Berlin

The luxury hotel Adlon after the Battle of Berlin

But what did this former luxury establishment look like? Debris all over. The floor of the great hall was covered with straw bales, wounded soldiers lay spread out. From the adjoining rooms a penetrating smell of blood and antiseptic circled the air. Doctors, nurses and medical orderlies were busy attending, all of them with tired eyes. I received my tetanus shot and the medal for wounded soldiers was handed to me, not too proud an award.

I ran into soldiers from the nearby Fuehrerbunker-headquarter. They told us Hitler and his staff were living deep underground in a bomb-secure extended bunker from where he is still giving his orders. He will remain in Berlin. There was also talk that an airplane landed at the Axis (Siegesallee) raising hopes that we might be able to leave the city. Many years after the war I read that Hanna Reitsch with Reichsmarshall Ritter von Greim landed with a small plane, stayed a few days and then returned to Rechlin. Hitler refused to leave.

With my hand bandaged and a sling around my shoulder, I returned to the Maikaefer barrack. Immediately I was assigned to an ammunition transport - a motorbike with a sidecar. I was sitting on the back seat, the sidecar loaded with ammunition. We were driving like crazy back to our infantry. There were no clear roads anymore, just debris, rubble, dense smoke, and artillery shells howling in the air. We got entangled in utility wires hanging down from split poles.

Picture above of Under den Linden gives only an idea of the clogged nature of the streets.

Picture above of Under den Linden gives only an idea of the clogged nature of the streets.

It was ghostly, not a soul around, eyes and nose were burning from smoke and dusty air. We could hardly distinguish ruins and obstacles when, not too far ahead of us, a Russian T 34 tank turned from a side alley into our road. With no way to turn around, we drove with full speed straight toward the tank and swerved around the corner into an alley, seeing how the tank's turret swung in our direction and the canon fired. It hit the corner of the ruin – another narrow escape. The munitions were delivered on time.

With a small group, I moved from the Maikaefer barracks to the cellar of the Deutsche Theater where we stayed put. The outside was under continual Russian artillery barrage - only a few houses away the Russians were dug in. The cellar was full of civilian refugees, mostly women and a few elderly men. They warned and begged us to empty the wine cellar, they were afraid if the Russians got hold of it a terrible consequences for the women would occur. We helped ourselves with the selected treasures and obviously overdid it, a kind of end-of-the-world mood.

The 1st of May was also approaching and we had all the more reason to celebrate, believing in a miracle victory. Champagne was flowing, close to an orgy when a shrieking “hurraeae” and wild rifle shooting broke out. The Russians stormed in. Stark awake, I ran straight away through the pitch dark night and saw a glowing object rolling toward me. I thought first it was a burning cigarette, but jumped into the next house entrance. A hand grenade exploded.

I felt right away a hit in my back and the left leg. No pain but I could feel warm blood. With a large group of soldiers I moved with great difficulty from the Friedrichstrasse northwards. They laid me in a communication car, more troops joined us and, finally, two armored vehicles with guns.

We moved through the part of the city which for days had been already occupied by the Russians. Along the side of the streets and behind ruins they were dug in, shooting at us. It was severe street fighting again, with heavy losses. After hours, about 800 to 1000 men arrived in Pankow (North Berlin), among them men from the bunker who told us Hitler was dead. Years later, I read that Axmann, the Youth leader, and Bormann were amongst us, and Bormann was killed.

Martin Bormann, right, and Artur Axmann, far right

Early in the morning, still within Greater Berlin in its northwest part, our column got bogged down. Everybody was dead tired, quite a few apathetic lifeless forms sitting around, waiting, no action.

I, the wounded little corporal, forced myself up and pushed toward the head of the column. There I pleaded strongly with a ranked officer, and might even have yelled at him to take over the command. It was his duty to lead and fight us through the encirclement. There was no way back.

So we formed ourselves into a solid formation and broke though towards the Northeast, still moving through villages with Cyrillic signs – Russians living there who, surprised by our appearance, ran away in panic. By using secondary roads and trying to avoid towns and villages we managed to proceed undetected. Some young hot-heads then started shooting at distant, shadowy Russian positions and, sure enough, we right away got their answer. Our unprotected column was an easy target for the grenade launchers. A shell hit close to the radio car where I was laying between a bunch of different cables.

The driver tried to swerve around, lost control and we tumbled down a slight slope. Like in a movie in slow motion I watched how we turned around and landed upside down on the roof. The crew ran away, but I could not, entangled as I was in the mess of all the cables. I yelled for help and finally a fellow soldier got me out of the rubbery pile. I had difficulty walking but with his help reached a near-by forest.

Under hedges of dense bushes we were all hiding. I could finally change my bloody shirt and a medical orderly tried to treat my terribly hurting foot. He cut my shoe up, blood and pus oozed. The grenade fragment entered my foot between the big toe and the ball of the foot. I would not let the man touch the wound; I handled it myself with a knife, scissors and tweezers. The excruciating pain drove tears from my eyes but I succeeded, and thanks to the tetanus shot I received a few days before I did not get an infection. Exhausted, I fell into a deep sleep.

They woke me up late and it was already pitch dark. We decided to march only at night and traveled a long semi-circle in a westerly direction throughout the night. The morning breakfast: we licked the dew from the leaves of the bushes and trees. For days, we had nothing to eat or drink. We were down to a small group of about 20 men, decided upon in order to avoid the more likely detection of a large column. We dared now to march during the day, found an empty house and some food – cans of pork fat. We mixed it with rhubarb leaves and gorged it down, resulting soon in running diarrhea. Horrible.

Worse was the sight at some other desolated farm houses we passed by of brutally murdered German soldiers, mutilated just a few hours before. We were terribly shaken, checked again and again the terrain ahead of us. Our movement slowed down, partly due to my inability to march by myself. I needed help and I got it, but I felt the eyes looking at me. For a short moment I thought to take my life. They took away my rifle and the hand grenade.

An old Berliner stood up in front of me and said he did not want to walk further away from his home town and would help me. It was a sad moment when I shook hands and said good bye to all the comrades with whom I spent the last days and nights so close to disaster and death.

*

We both looked for protection, dead tired as we were, and fell asleep under dense bushes. Unreal serenity greeted us when we woke. No canon thunder, no rifle shots, burning fires or thick smoke. Flat country with no people. It was a herd of bellowing cows, their udders full of milk, that woke us, We listened to the lovely song of birds and recognized spring was here, after all the past days of horror.

Only then we noticed a farmer and his wife chasing some of the cows, trying to catch and milk them. First they were scared when they saw us in our hideaway. When we spoke hesitantly in German, they recognized our worn-out uniforms and became very friendly and helpful. “You have to get rid of your uniform, otherwise you have no chance to avoid getting caught by the Russians,” they said, and told us they would bring us civilian clothes when dusk set in.

They had two sons who were both killed on the Eastern front. We lay around the whole afternoon listening to the cows still bellowing, the longest afternoon of my life. Then there was the farmer again, pulling out of a jute sack a whole bunch of clothes and in a brown bag boiled potatoes. Heavenly thanks.

We buried all our identification, the uniform, our dog tags, our military passbook, even family photos, and started walking - my comrade from Berlin putting his arm around my shoulder, I limping. We reached a large farmhouse, the farmer allowed us to sleep between his horses overnight. The first time we had a roof above our head and no frosty shivering. The following day, May 6th, my 19th birthday!

I had slept well and felt newly born. For breakfast we got hot milk, bread and butter – what a beginning of a day. Before we left the farmer asked for my camera and explained that the Russians would confiscate it right away or even accuse me of espionage. It made sense, so sadly I handed it to him. We were civilians again, a little strange but nevertheless a nice feeling. We walked along a narrow field path, progressing slowly; my foot hurt and I could not step on it. I realized I could not continue.

A small dwelling, very isolated, literally invited us to seek rest. A farmer's wife of about 55 years invited us to come in, immediately gave us something to eat and dressed my wounds. She was very helpful, very sympathetic and reminded me of my aunt Gritzi. When she realized how desperate my condition was she would not let us leave and offered us to spend the night in the barn. We accepted thankfully.

In the next days the pain in my foot became intolerable. Pus oozed out of the cut-up shoe. I could hardly make a step; I needed a doctor. The woman told me the next available doctor would be in Oranienburg, 40km (25 miles) south. Her farmhouse was about 3 to 4km south of Löwenberg, a road junction where Neuruppin-Eberswade crosses Neubrandenburg-Berlin.

We had to march to Oranienburg, a long way ahead of us. So we bid goodbye by to the dear, helpful farmer's wife and thanked her gratefully. She repeated to us that we were welcome to come back any time if we are in trouble. But I wanted to go home and see my family; I was worrying about what might have happened to them.

At a snail's pace we marched along a wide road, an important main artery to the South.At times, my Berlin friend pulled me in a hand cart, where I could sit. Many people, mostly refugees, wandered with us. They told us that today, May 9th, the remaining German army capitulated – the war was over. Then we confronted the first Russian soldiers. We were scared but they only wanted to ask us how we were, exclaiming "nix Krieg, nix Krieg” (no war, no war), giving us some cigarettes. We were relieved and marched on, soon passing by a column of German prisoners guarded by Russian soldiers. What a pity to see them and what luck had struck us.

The entrance to Sachsenhausen concentration camp

A little bit outside the city of Oranienburg, the town of Sachsenhausen is located. There we found out that the only doctor was at the KZ Sachsenhausen, pictured above. I did not hesitate to go there since I knew a KZ was a penalty camp for criminals. We walked first through a pine tree forest amid nice villas. I later found out those were houses for the SS guard. Then a big gate, where we parted, my friend and helper now wanting to return home to Berlin. There were fences with barbed wire and, after the entrance, a long barrack with a large Red Cross sign. Relieved, I thought I would very soon see a doctor.

But it didn't happen. Several strange-looking men wearing red arm straps, who I was told later were armed civilian Polish bandits, blocked our way, and when I told them I was injured and sick they yelled, "Du nix krank, Du muessen arbeiten.” (You are not sick, you have to work).

A broom was pressed into my hand to sweep and clean the ground. From other civilians doing the same job, I was told they were grabbed on the street and forced into the camp to work. When it turned dark I was driven to the exit – free again. Since nobody was allowed to be seen outside after dark, I was afraid to be caught and get into deep trouble.

Limping into a small alley amidst villas, I entered one – it was empty. I found a soft bed and fell into a deep sleep. Next morning, I rummaged through all the drawers, found fresh underwear and could, after quite a long time, wash myself. I did not know what to do. Continuing homewards seemed to be impossible. The words of the farmer's wife entered my mind and those words gave me strength enough to make it all the way back. It was also the fear of being caught again that made me forget my pains. I found a walking stick and marched on.

When I arrived late in the afternoon at the small farmhouse the woman greeted me like a lost son. I found out that she had a close relative - nephew, or even son - with the name of Willy and maybe, for that reason, took such good care of me. I had my own room, bed, table and chair, and felt like I was in seventh heaven. For breakfast I had real coffee with an egg since she had no milk. Lots of chickens but no cattle. She grew plenty of asparagus, which was unknown to me, but now very appreciated for its various dishes – soup and omelet and as salad with mayonnaise.