Wartime Service

- 3682 reads

Leopold Wenger's letters from flight training in Ochatz and Pilsen: 1939-40

- 4986 reads

'Bibi' Wenger enters the Luftwaffe flight service training and drops the Bibi to become 'Poldi from now on.

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by David Coyle

Oschatz, November 18th and 26th 1939: On Wednesday November 15th I set out from Berlin and was at the airport by noon. I’ve swapped Pomerania for Saxony as my new residence. Our accommodations are set in the woods, very nicely surrounded by the pines. We are five to a room, an agreeable number, and we have parquet flooring. None of us recruits is older than twenty-one.

Gilbert Geisendorfer learned of his success in his school finals at the very last moment in an inspection. At first it seemed his schooling was done, but that turned out to be deceptive for there is always more to learn, although of different sorts of things. During this time all the other soldiers and I have learnt a great deal in new areas. Naturally no one is flying yet. I’m doing well for cash: we’re on wartime pay like all soldiers and get 1 RM per day.

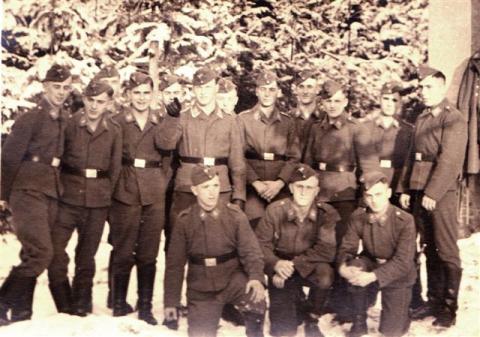

The recruits at Oschatz, 1939 (looks like 'Poldi in front on left -click to enlarge)

December 2nd 1939: We have been given the dates for our first leave. Christmas is out. This is the first Christmas I will celebrate far from home and family. But we've been promised that unless there is some unforeseen problem we will be on leave from December 29th until January 6th. No complaints, we recruits must be happy and thankful that we get any leave at all. Our fares will be paid.

We’ve put up Christmas wreaths in all the rooms and even in the corridor, so the barrack has taken on a festive look. We have now spent half of our conscript training period here on base, which naturally leaves us out of sorts. Tomorrow we'll be allowed off base for the first time. I’m not tempted and will likely stay at home, for I like it much better on the airfield than in the town, which is almost an hour away by foot.

Marching the recruits at Oschatz, 1939

Marching the recruits at Oschatz, 1939

On Thursday the whole company saw Franz Lehar’s operetta Der Zarewitsch. We liked it very much and found it a pleasant surprise. At one point our group leader arranged an evening party for us in the canteen. Of course, I don’t much care for these evenings of chat and beer guzzling, but you mustn’t isolate yourself. Besides our NCO is a sensible man, and the other groups can really envy us. An example: I was issued a brand-new topcoat, which one of the instructors tried to force me to trade for an older one; our NCO heard about it, and I kept my new coat. We all find him agreeable. About the locals: These Saxons! What a people! I like the Prussians much more, but men are creatures of habit.

My room-mates consist of another two officer cadets, a cabinet maker, a baker and a locksmith. A few days ago we officer cadets started wearing red stripes on our epaulettes, so we must be careful to put on a good show. I like our living quarters very much, except for the horrible amount of smoking. This is something I shall never get used to for it nauseates me at once.

Leopold in full dress as cadet pilot in 1939, Oschatz

December 9th 1939: Right, so I’ll be home on the 29th. Until then we shall be following a tough routine with no time for the celebrations. Besides, in these parts we shall be having recruit inspections over Christmas, and so there are daily preparations. My old classmates from Leoben sent me a card. It's hard to imagine being back at school again, and I don’t envy them. Here we have a fine life, even though the pace is “quick step” from morning to night.

Tomorrow we are again allowed out until 11 pm, and perhaps I will overcome my disinclination and go into town. Of course I'd much rather have my Sunday rest to sleep myself out. There is a big Christmas celebration planned for the company, but I think that if there is to be beer without limit it could turn out to be a booze-up.

Special Christmas party set up in the barrack - those definitely look like bunks in the background. We see 'Poldi 4th back on the left.

December 20th 1939: Now my recruit training time is done. On Monday we had our recruit inspection and it turned out very well. We are all happy that it is over and done with. Now we are having a quiet time of it, and it is such a strange feeling, as if every day were Sunday. Aunt Leni sent a Christmas package from Pernegg, and Grandmother sent a packet with apples from Gleichenberg. In addition the company made a fine Christmas celebration in which every soldier got apples, nuts, and cigarettes as well as a great Christmas stollen [a bread-like fruitcake]. And so my locker is as stuffed full as a hamster’s storeroom. I also have had my first trip off base, which was only good for more saluting than on the airfield.

We were all deeply shaken by the fate of our battleship “Admiral Spee”. This was certainly no minor loss for the navy. Here the candles burn every evening on the Christmas wreaths, and increase the anticipation for the holiday. I hope there is plenty of snow at home. In any event Willy should keep himself ready for ski outings. I am very glad that I can at least get home for the New Year. I am also very curious to find out what my little brother Gerhard looks like.

Poldi is home on leave for the New Year Holiday. The nation is at war; the faces of Dad and Mom show their concern as they toast the new year, along with younger brother Willy.

At the Pilsen Pilot School

Yesterday, January 21st 1940, I was the first to arrive in our room at about 8 pm. The last occupant arrived at noon today. The train was well heated and I got some good sleep. The barrack was much less pleasant . . . during the thaw, water had got through and some of the beds, chairs and flooring were covered with ice. Luckily, my bed was better positioned and spared. I turned up the heat at once and things improved before the first of my new roommates trundled in after midnight, one of them with a radio.

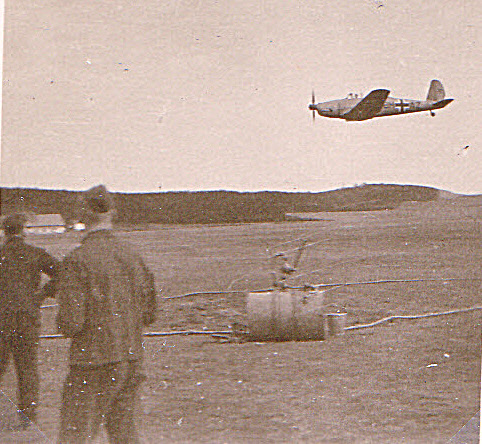

February 8th 1940: We have had a hard freeze and quite a bit of snow. But yesterday there was a sudden thaw. The miseries changed correspondingly: earlier feet were cold, now they’re wet. Today it was into the flight suit and furlined boots for the first takeoff, and then straight up. This is quite a different thing to flying a glider; now I’ve got to know Pilsen and surroundings from the air. It’s funny how small people and houses appear, almost like toys, quite unreal. I found it especially difficult to locate myself on the map, but it’s supposed to be hard in winter. I hope the weather stays as good as today for a long time; there’s no takeoff in bad weather. From 6,000 down to 1,000 meters you have such a wonderful, unobstructed view; couldn’t be bettered from any mountain-top. The first flight was in a Stieglitz FW44 and lasted 21 minutes; the second was in a Heinkel He 72.

Kicking off the first flight service

February 13th 1940: There’s a mass of news from home. More than anything else, I’m glad our boys from the west front will be spending their leave in the Untersteiermark [Styria] . . . I don’t know what I would give to be able to help. There’s not much to report here. The wonderful thaw stopped as suddenly as it started, and has turned to a shitty cold with slick ice everywhere under a dusting of snow. You cannot imagine the cold when flying; you must take care not to land with frostbitten cheeks or nose. By now I’ve been in the air quite a bit, and also been thoroughly bounced about. Every day must be used for training, so now even Sundays must be spent on the base while there is good weather. But we do as we please off-duty, so tomorrow I hope to visit the cinema. “D III 88” is playing. [A German film about pilots-in-training with a dramatic plot -cy]

There’s a story to tell about the canteen, for although our pay has gone up we also spend significantly more. Sadly, in this canteen there is everything to tempt a soldier’s heart, and we go past it every lunchtime—there’s beer, milk, spirits, eggs, sausage, etc. When I think how little milk you get at home, while there’s no limit for us here, I can only shake my head.

I hear that the school finals will everywhere now be held in February, which surely means the school year will also end early: Willy must make sure to finish in good order. The next time I get home on leave I hope my little sister will be less skinny, and Gerhard will be able to run to greet me.

Pilsen February 18th 1940: Yesterday afternoon we had fine weather, and I went up six times. Willy seems to think I’m flying a Ju 52. Quite the contrary: I’m flying a little two-seater biplane.

Poldi on his first take-off in a Stieglitz FW 44

Apparently a cold wave has descended on the entire country. Sometimes, the temperature is only -20º in the mornings. In spite of the fur-lined boots I have chilblains on both feet, which is not much fun. But we have been issued thick pullovers and warm scarves against the cold, and so far there are no cases of hypothermia.

Odds and ends: We have now also been issued walking-out dress and flat caps, though I prefer my old uniform. My thanks to Willy for the Condorlied, but as we sing it a couple of times almost every day I already knew it fairly well. I saw the film "D III 88" that Willy likes so much.

Heise [the friend from the Napola Köslin] is now stationed in Potsdam. I learnt from him that our Latin master at Köslin, Lieutenant Adam, has died on the Western front. I don’t know at all where Gilbert Geisendorfer is located. Neumitz from Steyer is in Mähren, and is also flying regularly.

I had to break off this letter as we still had flight duty this afternoon. I made five more take-offs. Visibility was poor today with considerable ground mist. It just now occurs to me: we will probably be able to choose whether to take our leave at Easter or Pentecost. If so, I'll choose Pentecost, I think that would be best.

At Pilsen, soldier-musicians entertain the living quarters

Pilsen, March 3rd 1940: On Luftwaffe Day we were off-duty in the afternoon, so I was able to get into town fairly early. I took the opportunity to shop for some items that are becoming scarce. Just about everything is available here, naturally not everyone has this chance, so please write and tell me what what you might need. For example, shoes, socks, shirts, yarn, etc. I’ll send the whole lot home as soon as the customs barrier is lifted. For myself, I picked up a flying shirt, socks, darning yarn and handkerchiefs; we had just got our pay. So write as soon as you can, so that I have time to get everything.

The weather here is now first rate and the snow almost gone, so that we can hope to put in a really good amount of flight duty. I flew eight times yesterday, and today we have our first free Sunday. A rumour is going the rounds that we shall be posted to another station. Well, well! We shall see.

Now to quickly answer Willy’s questions. Whether I also control all motion of the joystick? Willy will be excited to hear that we hope to be making our first solo flights by the end of the month. How many times I have flown? A huge number of times. And our flight suits are not heated. I hope that satisfies him.

Pilsen March 18th 1940: Last week I was on sentry duty Thursday and Friday, on exactly the day when there was a great parade of the troops through Pilsen celebrating the anniversary of our occupation. I was only able to see the fly-past in the distance. The weather was wonderful, yes so wonderful that the field thawed completely and men and machines were stuck fast in the muck. But now it has snowed again. It makes you sick. We were already celebrating the end of this rotten weather.

An early morning start in an AR 66. This shows the student pilot seat behind the instructor's seat.

Father asked if I was flying solo yet. This is the way it is—on the first flights the instructor sits in the front observer’s seat and we students sit behind him in the pilot’s seat. For some time now, I believe I can say that it’s quite as if I were flying solo. If the weather were only halfway decent, and the field a bit drier, then there would not be much missing to feel as an independant “lord of the skies.”

When my instructor wanted me to practice dealing with dangerous conditions, I flew above the clouds for the first time—we flew around, over and through the towers of cloud. That was quite undescribably beautiful, and we were also quite high. And then, pactice for emergency landing, a crazy business. The instructor cuts off the fuel and shouts, “Emergency landing!” At about 1,000 feet one must already have one’s eye on a likely surface. You come down any way you can, and get aligned for a landing. But as soon as the wheels touch the ground, the fuel is switched on, and up you go again. And this is repeated somewhere else from the beginning. Of course, the funniest thing is to catch a couple of people in a field, and then watch them tearing away from the machine roaring down at them.

You can see what fun we have at our work. Yesterday, Sunday, was Armed Forces Day. The local German population were allowed onto part of the airfield, and a couple of the instructors did some low altitude stunt flying. One of the hangers was cleared out and turned into a sort of beer pavilion. You are quite right, our machines are open crates, with just our heads peeping out. Willy would never see a thing without a couple of pillows packed under his parachute.

Pilsen, March 26th 1940: Easter is past, it was quite lovely. Of course I was lumbered with sentry duty on Good Friday and the following day as well, but on the Monday we took a very early bus to Karlstein, and from there on to Prague. Our Lieutenant treated us to this wonderful trip, and acted as our guide. First we looked over the Karlstein castle, the old repository of the Reich insignia. We also took our luncheon there and then went on to Prague, where we were given a fact-filled guided tour of the city. Partly by motor, and partly on foot we were led through the historic sites. We were in Hradschin in the coronation chambers under the care of the Reichsprotektor. Through the window of the Fenstersturz ["Defenestration" - Also see here], we gazed at a marvellous panorama of the city. Next we were in Wallenstein’s palace.

"Looking through the window of the Fenstersturz we gazed at a marvellous panorama of the city."

And watched the Czech Guards at the Hradschin (Hradcany) - Prague Castle

'Poldi took pictures at the famous Charles Bridge in Prague

and the St. Veits-Dom (Cathedral)

We had seen so much that we could scarcely retain it all. In the evening we still had two hours to spare, so we settled into a cafe in Wenzelplatz and looked out at the lively bustle in the streets. One would never see such a commotion in the streets of Pilsen. We returned to Pilsen during the night

The trip was a complete success for what I believe was our lieutenant’s plan, namely, as they say, to expand our artistic and historical horizons. For all of us, it was especially beautiful. In addition we were also given a holiday package: two cigars, 20 cigarettes, and two pounds of apples. They could have passed me over for the smoking supplies, but smokers among us were very pleased.

Pilsen, April 3rd 1940: Today was a very special day for me. After three weeks the weather was finally good enough for flying, and on top of that I was able to make my first solo flight. My dear Parents, I think it may entertain you and Willy to know how it turned out for me and how I felt.

Well, everything went quite quickly. First two flights with my flight instructor, then one with the instructor for the group, and then the front seat was empty. There were two little red flags marking the machine as containing someone “dangerous,” and warning all other machines in the air to keep their distance. At last I had the signal to start, and off I went at full throttle. Through it all I was not excited or unsure in the least: it was simply a repetition of the hand movements I had practiced so often, and for the rest I relied entirely on the feel of the plane. All through the flight I could feel the effect of the reduced weight it was carrying – all on it’s own the machine climbed up and away, and so I flew over Pilsen’s suburbs. And then came the landing. I had surely practiced enough, what could go wrong?

When I rolled back to the starting line, the flight instructor was the first to come and congratulate me, and then came all the others, all of them one after the other. With us, the first solo flight is a great occasion. Two others managed their first solo flights today so that this evening everyone is in great spirits. Altogether I was up five times solo.

So that’s the latest news. I’m sure you’ll share my pleasure over this first successfully completed test. I hope the good weather holds for a few more days so that we can thoroughly exploit this happy time. According to what we have been told, we may be reposted as early as next week, but so far nothing is certain.

The customs barrier into the Reich has still not been lifted. A request for Willy: could he kindly dig up Gilbert’s address for me? Willy flatters me when he asks if I am already a lance corporal. I’m afraid we will have to wait just a little bit longer.

To be continued -

Category

Germany, Leopold Wenger, World War IILeopold Wenger's letters from training to active duty in France: April-December 1940

- 2711 reads

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by David Coyle

Continued from "Letters - flight training 1939-40"

Pilsen, April 12 1940: We are in for a change again, and it starts tomorrow. The bags are already packed; we are to spend two months entirely on our own at a camp in the Böhmerwald [Bohemian Forest]. It is supposed to be first rate living there, and we are already celebrating. For the pilot's license, I must train for at least another six months; the first solo flight is only the beginning. In the overland training I intend to cover long distances, as a sort of survey of Germany. But this is still a couple of months away, for we must still learn a great deal about navigation, and without navigation there is no flying. Most failures do not come from a lack of flying skills, but rather from inadequate ability in navigation, and with that everything stops at once. Really Willy, how are things? I am surprised that he didn't join the Flier-HJ if he was able to.

"Our Klattau cottage"

Early morning just before start of service - Klattau

Adjusting the parachutes

Klattau, April 17 1940: We've had half a week here in Klattau, and I like it even if everything is fairly primitive. We are located about 7 km outside the city. There is only our group and a few people from technical personnel. Here, drill is greatly reduced, while duty periods are very tough. But here flying takes first place, which is quite to our taste. We get our post daily from Pilsen by a postal airplane. Yesterday was taken up with solo target landings from 2200 feet with the engine switched off. That was great fun.

Practicing target landings

High altitude flying "above the clouds" in a Go 145

Klattau, April 25 1940: I haven't written for a long time, but that comes from the fact that for the last while we've had continual flight duty from 6 am until 8 pm. In addition, I've had sentry duty, and on the 20th an inoculation which left me shivering with a bad fever.

On the 21st I finally made my high altitude flight. One and a half hours at 6,300 feet above ground level. I used the opportunity to fly over Pilsen and the Böhmerwald, until the time was up.

On the 23rd we visited a village Neumarkt in our own special way, which is to say we made a rough landing on a village meadow, which made a sensation all about. The schools were closed, and so all the town children came running. The people were pressing so much against the airplane that we had to bring in border guards to control them. For us it was a treat to see German civilians again, for the people in Klatttau [Czechs -cy] are especially horrible and loutish to the soldiers.

We have now completed the first part of our training, Class A, and have already started training on the heavier B machines. Today I shall make an overland flight in a machine of this sort. [Overland refers to landing in a different location than you started from -cy] Navigation in the Protectorate of Böhmen and Mähren [Bohemia and Moravia] is difficult because there are no distinctive lines or locations.

You already know that I am promoted to lance corporal, retroactive to April 6th. The theoretical A2 examination now awaits; there is a lot to learn, and the load is especially heavy because we are on duty until dusk and have no electric lighting. We shan't be here much longer; after the flying skills, which we've already begun, we go back to Pilsen.

"We visited a village Neumarkt in our own special way ... all the town children came running."

"We have already started training on the heavier B machines." Here the Ar 96.

Klattau, May 4 1940: It is of course hard for one of my old leaders who is still in Leoben. The most important man is Marek. Willy knows him. At the time, he led the illegal Hitler Jugend in Leoben. He also presented the first confirmation that HJ musters were held at our house.

It had been raining for the last few days which naturally means no flying; in its place we drilled like demons. But we didn't let it get us down, and looked forward to flight duty all the more.

We are currently training for solo flight skills. I really storm up into the air. Most people always enjoy this: spins, looping, sudden turns, etc. at 5000 feet in a Bücher-Jungmann. Formation flying with the heavy machines is less fun; one must be so careful to maintain formation that it is impossible to take in the scenery.

Next week our theoretical examinations are due, and so far we have had no time to study. I doubt that anyone has ever been trained as quickly as we have been trained. Until now the B 2 training took an entire year, and even then one was still far from flying a Ju 52 ... that was something for a C school.

I have still not flown an enclosed plane.

My chilblains are quite cured, but the skin has all of a sudden started scaling on my ears leaving sores. It must be the result of some mild frostbite.

In a recent comic event, I was flying an Ar 66 at speed, and wanted to hand-adjust the rear-view mirror on the upper wing. I reached up from the pilot's seat without thinking about the slipstream, which was so strong that my hand was struck backwards instantly. I have learnt to be more careful.

Gilbert has written that he is also flying solo.

Poldi took this picture while flying an Fw 58 over Klattau.

Klattau flight training

Pilsen, May 24 1940: Another week has gone by since we returned to Pilsen. It is so lovely here that our airfield is hardly recognizable. Must also say that our beautiful 1-A flying days at Klattau are also past. When we got back we had a few theoretical examinations to get through. A flying technique examination is in the waiting. And I am not done with formation flying. For the moment the routine is one day flight duty, followed by one day of theory. You will have noticed that in all of this I am to cover the requisite overland flight kilometers.

I flew with my flight instructor over Marienbad and Eger to Cham in the Böhmerwald, and then through the Fürth depression back to Pilsen. While flying, I had to show that I was able to continually track our progress by position and time. And as everything went well, on Wednesday I was given the job of flying a machine from Aigen to Pilsen. I was so happy to be back in the Steiermark again. Three of us were taken to Aigen in a W 34.

There each of us took charge of a He 72 and off we went over the Alps. It was a beautiful but very cold flight over the Pyrn Pass, Wimdisch-Garsten, and Wels to Pilsen.

That time I was in the air for two and a half hours, and yesterday I was sent up again, this time in an Ar 66 from Pilsen to Plauen in Vogtland, then over Ascha/Straubing to Ainring. This is the airfield which the Führer always uses on his way to Berchtesgaden [still today an important smaller airport in Bavaria -dc]. There I met others from our group who had also landed there. Unfortunately we had only two hours together as a storm was brewing over the Alps.

Today I flew to Ainring over Braunau am Inn [Hitler's birthplace], then over the Böhmerwald, past the Großer Arber [highest peak in the Bavarian Forest] and over Klattau to Pilsen. I was quite tired, and had eaten hardly anything the whole day. Since we get a special issue of rations for every hour of flying time, and because, so far, out of simple haste I have left behind the on-board rations, today I was issued more than I could reasonably eat alone: a liter of milk, two eggs, chocolate, biscuits, 10 rolls, a double ration of butter, glucose and cream slices. In just two days I've covered 1100 km; if this continues I'll reach the target number all too quickly.

We hear daily of the successes of our troops with enormous happiness and excitement, but are annoyed that in all likelihood we will not be sent into action, because it will still take some time to finish up here and then to go through our specialization training.

Pilsen, June 7 1940: Unfortunately I was not able to write sooner. We have now all completed our overland kilometers. In the process I have traveled a lot. I've been in Breslau, then in Brünn. On May 28th I flew to Straubing (on the Danube), from there over the beautiful Thüringer forest to Gotha, then over Bayreuth, and finally from Gotha over Saalfeld back to Pilsen. Then the weather was so bad that we put in a few days of infantry duty.

On June 1st I flew to Weimar with my instructor over Marienbad, Eger and Plauen in quite miserable weather. While I was there I met a flier from the same time at Köslin [Napola], who is stationed with Gilbert in Berlin. In the evening we went into Weimar together. The next day we flew back to Pilsen in the afternoon. On June 3rd I flew to Straubing, and then to Braunau am Inn, and back over Klattau to Pilsen.

On June 6th after putting in a four hour flight, I had my examination in flying skills. And now we are to learn radio-navigation. When I use the radio, I work very slowly and carefully which reminds me of our days as recruits. I hope to complete the B 2 school during the summer holidays, but everything will need to work out well. If so, then perhaps I can get a couple of days' leave.

In a W 34 over Cham

Poldi (on left) and fellow airman returning from a cross-country flight

Ainring, July 7 1940: You will be surprised that I am writing from Munich. I was very surprised myself to be sent here today, especially as we had been told that we would only be flying on tomorrow. So I have time to write, but I am without my fountain pen, hence the pencil.

From June 20 to 30 we trained at an airfield in Cham in the Böhmerwald. Here we flew the whole day through, from morning 'til night, once even flying through the night until 4 am. This continued in Pilsen, with the difference that overland flights were added. One day my instructor and I set out for Klagenfurt, but the fog over the Alps grew so thick that we got thoroughly lost in our great two engine machine until we were able to make out Windisch-Garsten after the Pyrn Pass. From there we turned towards Wels. Once I made a very boring bad weather flight to Markersdorf near St Pölten. There we were grounded for three days by the weather. Flying these days is more fun than it was in the small machines; we now fly with a crew of four.

The latest flights to Prien, Cham, Bayreuth and Munich have been “instruments only.” Naturally we always have an instructor on board with a radio. It is, of course, not very cheering when we are curtained in and can see nothing of what is happening outside. But according to our time table, we must take off in just this way. In this way we leave Pilsen in the early morning, make three or four stops through the day and usually get back to Pilsen about 8 pm. Then we quickly wash and eat, and fall into bed to be ready to repeat the performance in the morning. All the same this can't continue much longer; time must be set aside for theoretical instruction.

Pilsen, July 1940: I should be very interested to know how things turned out for Willy in school. Today completes half a year since I returned from leave; Gerhard must have grown a lot. We are done with the flying part of our training and haven't flown in the last fortnight. Next week the theoretical examinations begin. Only there is no time for study, because we are always drilling; we even spent today, Sunday, racing about the countryside.

On Saturday we were on duty until just before 10 pm. Any comparison between school here and Oschatz is laughable, but that's the way it is for officer recruits. We are to be finally posted on August 13th. Unfortunately we completed our training three weeks early, and now must wait until the time is up, consoling ourselves with drill. It used to be always so, that when the group finished up early, we could go on leave, but we officer recruits make a special case, we call ourselves the “penal colony.” We are happier about the the new posting where we shall at last begin our specialised training.

Pilsen, July 1940: Today I took my two last oral examinations (airplane engines and meteorology), and with that our group has completed its studies. That is to say, we are now the Luftwaffe's youngest military pilots. Over the next few days we shall be issued our pilot certificates. Naturally, I have already ordered a pilot's dagger from a firm in Berlin, and I shall be very happy when I can wear it for the first time. Now that we are done with the schooling we drill from morning to evening, longing for our marching orders and new postings (but these may take another two or three weeks). I am very anxious about where I shall be posted. I have applied for Stukas or fighters. I should much rather be able to spend the time at home, if the whole family were gathered together.

[During the holidays, our mother took the children to our summer house in Bad Gleichenberg.]

Also, I was taken aback to read that Willy cycled the entire 130 km from Leoben to Bad Gleichenberg in a single day. That's a fine achievement for the young rascal.

Pilsen, August 3 1940: Dear Dad, I write in great haste before going on duty. Thanks for your letter which came in yesterday. Except, to my horror, I got the letter as a personal delivery by the sergeant major himself, instead of through the post as usual, and got a tongue-lashing into the bargain. The point was that you addressed the letter to “Military Pilot ...”. Now that we are at war, there must be no written identification of anyone as cavalryman, rifleman, or airman, only the strict military rank, in my case lance corporal. So please, dearest Papa, write only to Lance Corporal L. W. etc.

Pilsen, August 15 1940: Today I can share a pleasant bit of news. After 4 weeks of quite hard drill we had an inspection today and we have also been promoted to NCOs, and this, retroactively to June 1st. I can't tell you how happy I am about this, even though we had been counting on it. Now we are going about with our new uniforms, and it is an amusing feeling to suddenly become a superior of the other ranks.

Together with the promotion, we have been told where we shall be posted next. I am to go to an airfighter school at Schwechat near Vienna, where I shall get my specialised training. Sadly nothing has come of the Stuka dreams. In spite of that I am glad to be sent a bit closer to home. Besides, it is perhaps possible, dear Papa, that you can come to Vienna with Mom, where we can meet.

This evening we shall be stepping out with our officer supervisor to a bar in Pilsen for a farewell celebration. It will be our first evening outing on which we are allowed out with limits set according to our new rank: until 2:00 am. And tomorrow it is off to Schwechat. I am already curious to find out how my new quarters will look. Hopefully I shall not be disappointed. From now on, besides the regular pay, I shall be getting a professional soldier's salary. It is supposed to be generous; I shall let them surprise me.

Special Training in Schwechat

Schwechat, August 17 1940: (to Mom in Bad Gleichenberg) I don't know whether or not you already know that I have been transferred to Schwechat. It is still not certain whether we (I am here with 11 other officer recruits from Pilsen) are to stay here, will go on somewhere else, or even be able to go home on leave. I have been granted my first outing to Vienna: Sunday until 2.00 am Monday. The airfield is here in Schwechat, quite a distance away, with a station on the line from Pressburg to Vienna, and from which station I shall be most often travelling to Vienna. I am very glad to be out of Pilsen's wooden barracks. Here we have lovely stone buildings again, and I share my room with three others. I was in Vienna on Sunday and saw the Technical Museum there.

(Dad and Willy met with Bibi in Vienna.)

We have been assigned a Fähnricht [Ensign] supervisor. He has talked of a steamer trip on the Danube, over Saturday and Sunday.

Schwechat Fighter Pilot School with "lovely stone buildings."

In front of the hanger at Schwetchat

A Stuka Hs 123 at Schwechat

Schwechat, September 30 1940: Yesterday and the day before I was in Vienna again. And Saturday evening I was at the Staatsoper to see “Madame Butterfly.” It was wonderfully beautiful. The opera itself and the staging alone were wonderful. I liked it very much. I had quite a good seat for only 3.50 DM, the price of course reduced by 50%. We got our tickets so very inexpensively through our Wehrmacht care station. Otherwise the best seats cost 40. DM

I am now promoted to Fähnrich [lowest grade in the Prussian officer hierarchy -dc] retroactive to the first of the month, and can now wear a portepee [part of an officer's kit in the form of a decorative looped cord with a large fob, intended to be attached to his dagger -dc]. I had been an NCO scarcely a month and so the promotion came as a great surprise. This time the order was announced directly by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and so was made effective a bit faster. It is really something the way so many of our instructors from Pilsen, who were still our superiors two months ago, must now produce stiff salutes for us. In the coming month we must be as good as done with our specialised training. Then I hope that we shall finally get a few days leave. It would certainly be good for all of us. I have already been retrained for the Me 109. This is a very fast bird.

Schwechat, October 9 1940: Last Sunday there was a military concert in the city in front of the Johann Strauß memorial. That was another one that I made sure not to miss. On Saturday I shall probably go to the opera again for Verdi's “Don Juan.”

Schwechat, October 30 1940: Imagine my rotten luck: Saturday morning I get tickets for a Sunday evening performance of “die Meistersinger.” And now we are ordered back to base by 10 pm. Annoying because it would have been my first Wagner opera.

On Monday, that is, tomorrow, we shall practice firing from the air with the Me 109. This is a marvellous thing; I am already very happy about it.

Cranking the engine of an Me 109

Flying the Me 109 - "a very fast bird."

Schwechat, November 3rd 1940: On the 15th, on my first military anniversary there is to be a final inspection. What happens with us after that, no one knows. The three months in Schwechat have gone by so quickly, and I can scarcely believe I could find such a pleasant life anywhere.

Schwechat, November 11 1940: On Wednesday November 10th I was given my pilot's badge. No need to say how happy I was about it. I wore it for the first time yesterday in an outing to the Burgtheater (“der Kanzler von Tirol”).

Luftwaffe pilot's badge

Schwechat, November 13 1940: On Friday we set out for foreign parts. I am to go to Merseburg an der Saale near Halle. For what reason, I have no idea, and neither have I any great desire to be annoyed by my dear friends, the Saxons.

Merseburg, November 17 1940: We arrived after a trip of almost 24 hours. The arrival reminded me very much of Oschatz, and also we were all unpleasantly disturbed when we saw the internal arrangements here for the first time. In Schwechat we had divine peace and quiet. Towards the end we were only two to a room, which was very pleasant in itself. The only thing that has pleasantly surprised me, is the casino which is grown very large. There is no hope of leave from here. It is also unclear how long we are to stay here; depending on circumstances, it may be for several weeks.

The family enjoying Poldi 's two-day November leave in Leoben: little sister and brother, Gretl and Gerhard, and Mom and Dad (with bicycle). Photo probably taken by Willy.

Merseburg, November 24 1940: [Surprisingly Bibi was, all the same, given another two days leave.] I arrrived here early, just after midnight. The trip went very pleasantly. I was only obliged to change trains once, and that was in Nuremberg. From there I caught an express. There was only two hours waiting time in the entire trip, and so I arrived here 15 hours early. It is a great annoyance that there is no later train to Munich. The NSV [National-Socialist people's welfare] was distributing sweet coffee and soup to the soldiers. So I started to eat my sausage buns, and to nibble at Mom's cake. Things have also changed a little here. Although I was only two days at home, it feels as if I had been with you just as long as last time.

Active Duty

France, December 5 1940: [The final location could not be disclosed, but was surely in the environs of Le Havre. -dc] Our journey that began in the early hours of Sunday morning came to an end this afternoon. As you can imagine, I saw a great deal in this time. When our rations were distributed in Aachen I sent a quick note. I hope the card was also received. From there we went to Maastricht, then through Belgium, Liège and countryside. Here I saw the first traces of the war.

The little I saw of Holland was very nice, while I didn't care at all for what I saw of Belgium. Then we traveled on through the night arriving in St Quentin at daybreak. One area of this city is entirely destroyed. Then it continued at an unbelievably slow pace -- mostly because so many bridges were out -- on to Compiegne, where we arrived at 4 pm and got fed. Here, the entire area about the station was completely destroyed. Naturally, I took photographs whenever I could, but the weather was almost always bad.

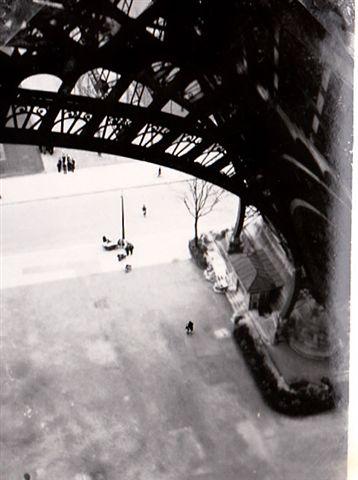

I was happy when we got into Paris at 10 pm (December 3rd); we had all had quite enough of the train travel, even though we were in a 2nd class compartment. Sleep was scarcely possible. I spent the first night sitting; the next night I climbed into the luggage rack at once. In Paris we finally got proper beds and food from the Red Cross. On December 4th our train was only to leave in the afternoon, and, even though Paris is off-limits for soldiers, the Wehrmacht treated us to a thorough tour. So I managed to take in the most important sites in the little time we had: Napoleon's tomb, Place de la Concorde, Eiffel Tower, etc.

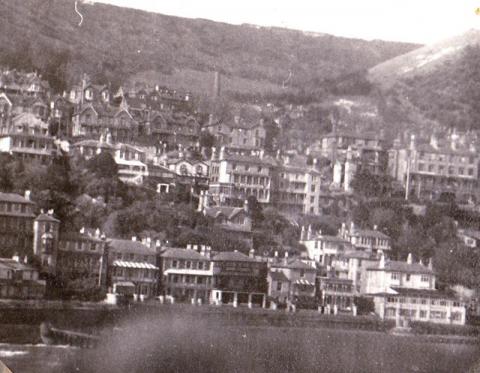

We travelled through the night, and reached our unit at midnight. I stayed the night in a country house. We waited through the morning sitting over an open fire in the living room; in the afternoon we were travelling again. I am now located in a small town in Normandy in provisional, i.e. quite miserable, quarters. ...I have already been into the town this evening. It is in any event more agreeable than Merseburg. I don't know whether or for how long I shall be stationed here. As I write we can hear the bombers overhead, rumbling on their way to England.

As far as the people here are concerned, they live fabulously well. This evening I ate, in what is called an “hotel,” a great roast of lamb, white Bordeaux and oysters. Everything was quite inexpensive, although prices are supposed to have gone up significantly. I am very glad to have been able to have one more time at home with you, even though briefly, for otherwise I should have had to spend more time on the train, even with good connections. I have nothing else to tell: I am doing well, like “God in France,” and I am in good health. [So as not to misunderstand, “like God in France” is a proverbial metaphor meaning to live luxuriously without cares -dc]

France, Dec. 20th 1940: My Dear Parents, The Christmas celebration is getting nearer, but we have not noticed it much here, for neither the weather nor the surroundings produce any sort of Christmas mood. It is still relatively warm here. The temperature stands at about 10° (centigrade) for days on end, so naturally there is no question of snow. We put some effort into finding a Christmas tree, but there was none to be had anywhere. We have been told that a few are still being sent from home. Duty is very agreeable and varied; most commonly we are on watch, waiting for the Tommy who never appears. Day by day I like this room better. Now I even have heating in three forms: hot water [radiators], warm air [ventilation] and an open fire. So the room is as cozy-warm as a bakery. The food is equally superior. Every day we even have as much wine as we please. One needs some restraint to avoid becoming a drunkard.

I wonder if you've received all my letters, as I've written a good deal lately. Well, it's past midnight, so I must close.

Dear parents, I wish you and my brothers and sister the merriest of Christmases; I shall be with you in spirit.

Heartfelt greetings and kisses from Bibi.

France, Dec. 28 1940: The Christmas festivities are over. We used a pine for our Christmas tree as nothing else could be found. I was the one who hauled the tree from 60 miles away in my truck. Now our Christmas Eve: our celebration was just for our unit. We started with our roast hare and the usual side dishes, then the famous Christmas stollen, and lots of apples, nuts, etc. There was wine, sparkling wine, beer and spirits until we were senseless, more accurately falling-down drunk. We also hired a band composed of men from the air-defence. “Father Christmas” appeared and distributed presents. Naturally I was thinking of you the whole time.

We are a hour behind you so that as your tree was burning it was still broad daylight here. In general there was not much in the way of Christmas spirit.

On Christmas Day 1940 Poldi is in the "Sitzbereitschaft" (readiness seat).

On the 25th I was on observation duty again, which means being in position at first light, and staying outdoors the whole day. On the 26th I was in the military cinema ... and that's the way time goes by. As far as I can tell the French don't celebrate Christmas at all—I found a single shop stocked with cakes.

Wine on the other hand can be had everywhere. So there have often been days—I confess it to my shame—that I've fallen into the feathers with a fuzzy head.

As for everyday life and doings which Dad asks about: Basically I still have a lot to learn here, and must get used to the new surroundings.

I had my first enemy contact on December 10th. This is how it came about: I was on observation duty and complaining because lunch was late, then I heard motors, and thought it was the truck bringing the food. I looked out at the window and suddenly saw bombs exploding. I was told that I said, “Those are really bombs.” At that point everyone was under cover; but then we raced out to the machines to “scramble” after the Tommy. But he immediately disappeared into the clouds over the Channel. We hunted him over the water for a long time, but he must have raced off like a poisoned ape.

On the same day we chased another one, but it grew dark so quickly that we had to feel our way along the coast to get back to our airfield. Today I had another contact which had been spotted by a submarine. Naturally they didn't wait for us to catch up with them. Every night our position gets shot up, and the air-defence puts on a fine display of fireworks.

It is unbelievable how much the people took Major Wick's death to heart. I was so happy to have been posted to his wing directly, and now I shall never see him again.

End of letters from 1940 -

Category

Germany, National Socialism, World War IILeopold Wenger's letters from France: January-April 1941

- 2364 reads

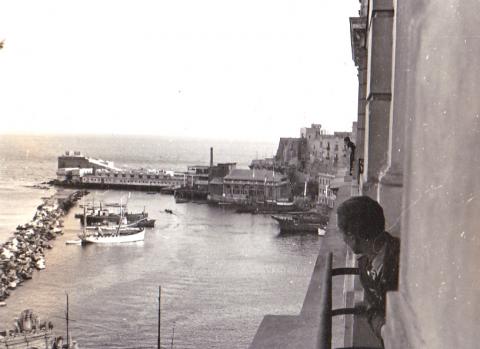

"I am on the beach almost every day," writes Leopold Wenger to his family from his location in France on the English Channel coast.

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Hasso Castrup

10 January 1941: Today I flew for the first time in the new year and have seen England's coast for the first time. About the false alarm in Leoben on Christmas Eve, I had to laugh.

So far none of us can fly! And for us, there are no more air-raid alarms; there is no time for that—bombing starts immediately.

20 January 1941: Today, all the snow has melted away. It's positively unpleasant—you can hardly believe it. The soil is just bottomless. It looks like Spring wants to begin already. I am almost every day on the beach, watching the sunset again and again, a truly wonderful, impressive experience. Today, however, there came up a very violent storm and I had to think of Mom whose desire has always been to experience a storm at sea up close, with lashing waves. Our guards, however, are less enthusiastic about it.

8 March 1941: [After returning back from a vacation] I came back to my hotel half an hour ago, at 20 hours, and since I am a worthy son, I write immediately. I had a long stay in Trier. This morning, I arrived at 11 o'clock in Rouen, and I stayed there till 17 hours. I looked around in the city and saw what was there to see. The cathedral, harbor. Finally, I went to the soldier cinema. I came back with the last tram just before the front door closed for the night.

9 March 1941: I've been back for a whole day here, but I cannot accustom myself to the routine. I have not done any real service today, so am enjoying the Sunday. I have met a few people and had to report everywhere that I'm back. This afternoon I brought my place in order and then I paddled in the park lake. While I was away, a few of our men found somewhere two old paddle boats with which we now paddle in our "lake" and stage great naval battles. Only it's rather embarrassing if you fall into the water and are then soaking wet.

"This afternoon ... I paddled in the park lake ... it's rather embarrassing if you fall into the water..."

Incidentally, today was a wonderful day, a real Sunday. At first I took a walk on the beach and then went to the soldiers cinema, and then again at the beach. Everywhere was choking full of people. I met a few friends who were going to take a ride with their motorboat. I was happy to join them and it was a wonderful boat trip. Finally, we docked at the pier in the middle of the night. Anyway, it was very funny.

Some terrible news today: On March 1st ration cards were introduced for all sorts of things. And I was going to have a suit made. I hope it will still be possible.

Poldi and fellow pilot enjoy the early Spring sun at their lodgings in Le Havre, March 1941

13 March 1941: Since I got back I have not flown even once. But we have to do all kinds of nonsense.

Here I will hardly get to fly because I have to go somewhere else, here in the area. I'm curious if it will be less stiff. I have not yet been to the city before closing time. I have bought only vanilla; was not able to buy anything else. I will hardly get any shirts, etc., precisely because the ration cards have been introduced and it is forbidden for us to buy fabric. I will try my best.

On Monday, March 10th, we experienced a fairly loud midnight concert of flak and bombs. This time, Tommy had come with several machines. Sometimes we could see quite well when our anti-aircraft gunners caught them with the searchlights. You can imagine the hellish concert. One machine was hit, then tipped over and it probably plunged into the water. The next day we visited the bombed location. It all went wrong for them (the Brits). A whole lot of duds were lying around everywhere. The streets were littered with flak splinters. It has literally rained with splinters.

17th March 1941: The only thing I could find to date, as regards Mom's wishes, was vanilla. [French vanilla is famous -cy] While I cannot imagine what you can do with this black stuff, I hope Mom finds some use for it.

The chocolate is for my dear sister for the hair-cutting. And as to the iron: the large fragment is from a bomb that I saw strike on 20 December last year, the small ones are from anti-aircraft shells, which rained down on the night of 10 March. Please keep all of this for me!

For Mom, I got this fabric. I've already sent a similar one. If Mom can not use this stuff for herself, then use it for Greterl. I've also caught a starfish, cooked it, eviscerated and dried it. I think I did quite a good job.

Our new pilot accomodations, Beaumont le Roger

21 March 1941: Beaumont le Roger Now I have again changed my location and lay no longer by the sea, but in a small town. The journey here with the truck took a whole afternoon. In this nest, you can buy nothing at all. There is no decent restaurant, pub or cafe, nor a department store. Thus, one is forced to be thrifty. We look like pigs, dirty from all the dust. Our first question was, of course, where is the bath. We are now two ensigns, a senior cadet (at the moment) and lead a great life. We live in a very nice, pretty garden.

Beaumont garden, above, and Laundry, below

On the first evening we were all greatly welcomed. In the morning, and by 2 o'clock, we had to stop the attempt to drink us under the table. At the welcome evening we were also asked who was the youngest and it turned out that I am. A packet was handed to me, to my surprise, which said: to the youngest pilot of our unit. This [treatment] is not hard to put up with! Incidentally, I have just sent 3 packets to Leoben.

1 April 1941: Well, I've been waiting eagerly for Dad's report on the reorganization Gleichenberg. In the summer I would quite like to come and see it for myself.

I have a lot to learn and it buzzes in my head—only tactics and more tactics! But it's all new to me and very interesting. Of course, I do no flying here. Our Mom will be somewhat calmed by that. But for me it is a disadvantage, since I'm out of practice. Willy should learn English properly because, if he wants to become a pilot, he must bear in mind that one can use this language in many places.

11 April 1941: Effective from 1 February 1941 I was promoted to Oberfähnrich [corresponds to sergeant first class]. Within a few minutes, this occasion started an evening with booze since we celebrate everything that comes our way.

"Effective from 1 February 1941 I was promoted to Oberfähnrich..."

13 April 1941: I have been on duty at the command post in the afternoon and, to our surprise, we had to leave the base, so that our festive Easter lunch got cold. Our orderlies, crafty guys, had purchased chicken for us pilots and let the cook roast them for us. We have been looking forward to it for days and then suddenly there was an alarm ordered (readiness). When we returned, the food was cold of course, but still very good.

Our squadron's insignia, which is painted on our machines on the snout, shows a sword lying perpendicular and the inscription: "Horrido." A hunting call. This squadron was once led by squadron commander Helmut Wick. The hit list of the squadron is very high.

Now almost every night we have seen and heard our night bombers fly to England. Tommy comes very rarely, and only in case of unfavorable weather, with low clouds—only then they fly. But if even one of us comes up there, he runs away, dropping his bombs no matter where.

19 April 1941: We are still having a lot of fun. We are once again on the move. Today we have moved and early tomorrow morning we are to proceed further. How much I like that, you can imagine. But it's also great fun to see something new all the time. As a result of an error, I am again without my luggage; it is a few hundred kilometers further, somewhere in a column which I will meet in a few weeks.

25 April 1941: (probably Cherbourg) I was for all this time away, as part of the advance party, and now live in a city in a hotel. It would be quite as nice here, but we must stand in readiness from daybreak to dark, and that is from 5 hours in the morning until 22 hours. That we are really tired then can be imagined. You will surely see our lieutenant in the newsreels, because he has just scored his 20th air victory (Lt. E. Rudorffer). I'm now back to flying after quite a long break. Incidentally, two days ago I became a Lieutenant. Now I must go to Paris to procure the most necessary items.

Poldi becomes a Lieutenant!

29 April 1941: Today I returned from Paris. I was like a pack mule. I now have all the accessories and materials for breeches, long pants and a tunic. Now I just need a place where I will stay longer and where there is an uniform tailor. I have also bought a leather coat. It is perfectly designed, sits wonderfully and has a warm lining. Only it is unusually heavy. It is, of course, Luftwaffen blue. I could not find suitable boots. I still have the ration card. Now I only lack the dagger, but I did not want to buy it in Paris. For Willy, I could not find any other slippers than those from a Moroccan store.

Yesterday I was at the Eiffel Tower for the first time. The railway travel is pleasurable because I now get tickets for the second class.

Poldi's group taking in the view from the Eiffel Tower in Paris

Looking down from the Eiffel Tower

The young airmen viewing the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, April 28, 1941

The German soldiers' cinema in Paris

To be continued ...

Category

Leopold Wenger, World War IILeopold Wenger's letters from France, May-December 1941

- 2536 reads

'Poldi in Brest, France, 1941, in his Me 109

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Markus

Continued from Jan-April 1941

1 May 1941: [Still in the city of Cherbourg] Drunk sailors are found in all corners today because it is a common holiday. I used this free afternoon to thoroughly sleep myself out because where we live, and get up at 5 a.m. for emergency service which lasts until 10 p.m., drastically gets on one's nerves. Then the commuting from the city to our squadron location takes another half hour. I will be happy whenever I can go back to my squadron, which is heading further West.

How are my two little siblings doing? Is Gerhard still so terrible? [2 years old] Or has he gotten better? And Greterl [6 years old] ought to get her hair cut again, for then I will send her chocolate.

What did you say when you heard that I got promoted to lieutenant? It went quite fast. I was Oberfähnrich for only 12 days. I didn't even get a wage increase for being Oberfähnrich; a big lump sum will be paid all at once.

What did you say when you heard that I got promoted to lieutenant? It went quite fast. I was Oberfähnrich for only 12 days. I didn't even get a wage increase for being Oberfähnrich; a big lump sum will be paid all at once.

Right: Someone snapped this picture of Lieutenant Wenger being saluted as he walks past sentry guards on May 7, 1941 in France, wearing his long coat.

2 May 1941: On a recent night, I was surprised by a bombing while walking home from the cinema. I heard seven bombs howl and fall. They banged terribly and I had a bad feeling when one bomb after the other exploded closer and closer to me; You can imagine how I ran!

Today I was resettled into another hotel and have got a very nice room. I live right in the middle of the city next to the beach. [Cherbourg-East?]

9 May 1941: Yesterday, when I came back from Paris, I had received a lot of mail. Today I returned to my old squadron on a very slow train that took 11 hours! We are now even further to the West, but still on the Channel. I have again a nice hotel room with a bathroom (but there's no running water at the moment).

The landscape and town are more beautiful than I'm used to seeing so far in France. On the coast of Normandy it looked similar to how Dad had always described Dalmatia. Every small garden is walled in, for up there a steady wind blows. Here in Bretagne [Brittany], it rather looks like Eastern Styria from what I can tell from the train ride. Hilly, small valleys and streams, blossoming orchards. There's just one thing I don't like, and that's the cold. It just doesn't get really warm. Even when the sun is shining high in the sky, there is this cold breeze off the sea.

When I was in Paris I visited all kinds of attractions. I had already seen the Triumphal Arch in April, but I went up onto a roof from where I had a panoramic view of the whole city. I also flew over Versailles and landed close by. [Le Bourget?]

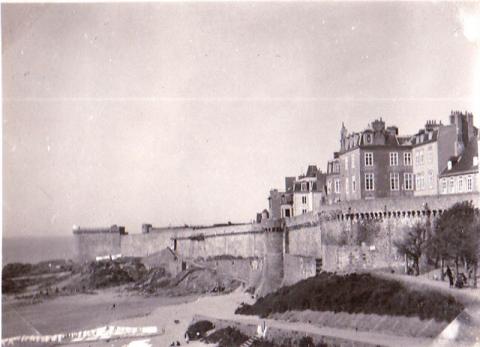

The beach at St. Malo in May, 1941

The close-by seaside resort of Dinard, May 1941

May 10th, 1941: Yesterday evening, I went for a little walk in the city [probably St. Malo], and I have to tell you, this is the nicest place I have stayed in France. It seems to have been an ancient fortress with old city walls, military towers, ring ditches [moats] and marvelous parks with beautiful plants. The chestnuts are blooming now and so are most fruit trees.

Yesterday, one of our sergeants shot down a Spitfire. Our Lieutenant Rudorffer, who just scored his 20th air victory, was mentioned in the Wehrmacht-report a few days ago. On May 1st he received the Knight's Cross.

25 May 1941: [Theville?] Two days ago, we moved again. I received Willy's outraged letter:

(I had already started with the SG38, the training glider, that is. I was in the seat, was instructed, and all of a sudden an incoming rain prompted the flight instructor to take me off the plane. My 130km bike ride to the airfield was in vain, and I had the same distance to go back. Note from W. Wenger)

I felt sorry for him because of his misfortune, but at one point he will get his turn flying also. Maybe he has already done his first starts by now as I'm writing.

I, as well, complain about bad luck lately, for firstly the tailor bungled my uniform so that I can't really wear it now. Because we had to leave so suddenly, I was forced to just take it with me and have it repaired by another Frenchman, if that is even possible. During a flight, something broke in my engine. Fortunately, I was very high over the Island of Jersey and able to glide back to my airfield. Only a few days later, I had an engine falure during a test flight. And yesterday, I had to land on an alternative field due to bad weather. There, a mechanic steps onto the wing, slips and trashes the landing flaps. It's not getting any crazier than that.

Over the last days, one of our squadrons sank a submarine and a 2.5 ton steamship. The submarine goes to the account of Lt. E. Rudorffer.

11 June 1941: After I came to Cherbourg from Dinard, I am in now in the westernmost West of France [Brest]. I've now flown over the Atlantic Ocean. I'm in a nice lodging again, right next to a park with palm trees and agaves, close to the shore. We have a small sailing yacht with an engine. But we don't use all this to its fullest, for there is just not enough time and motivation for it.

In the meantime, we've experienced more bombings. They dropped three right in front of our house yesterday. I saw one machine crash and burn. The Flak always gives us a nice fireworks display.

I am well enough; it's just that my bad-luck streak continues. I damaged the engine of my machine when rolling it; then a suitcase got lost during my last transfer [relocation].

Lt. Wenger, on stand-by at Caen in early June, talks with Obergruppenführer Limberg (the big guy).

Landing an Me 109 - the most produced fighter aircraft in history with 33,984 airframes from 1936-April 1945

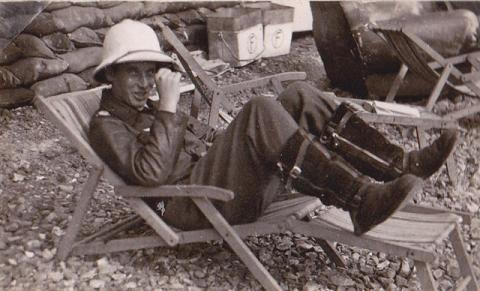

29 June1941: (Cazaux) Recently I was in Paris again and from there we drove on to Bordeaux the next day. I'm having a great time here at the moment. We are in an isolated place, close to a large lake. All around, there are only woods. The nearest village has a population of about 300. Nevertheless, it's very hot where we are, measuring 50-60° C daily. All the men were given tropical helmets. I had a tailor make a light uniform jacket out of tent fabric. Today, it was especially hot and so I'm running around in tracksuit pants almost the entire day. Our guards wear cloth-suits and white tropical helmets.

Bordeaux, France, June 1941

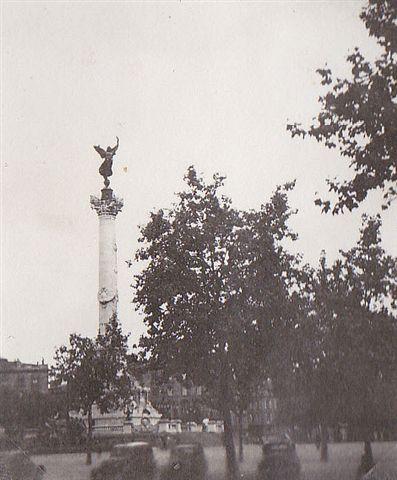

Place Gambella, Bordeaux 6-41

"Ground staff" at work in the intense heat at Cazau in Southern France, July 1941

Technical service carried out under camoflaged hanger at Cazau

Right: There is also time for cooling recreation in Lake Cazau in their own sailboat. Temperatures reached between 50 to 60 degrees centigrade in July!

I was unlucky again yesterday! I wanted to take a sunbath after bathing. I laid down on the sand beach; a fresh breeze came from the Bay of Biscay and it was even pleasantly cool. I fell asleep and after about two hours woke up in pain, all burnt by the sun. It's difficult to walk today, so much does it hurt everywhere. There is no drinking water either. Brushing teeth is best done with bottled water. If we run out of that, then we use wine which we have in abundant quantities.

There is plenty of flying here, again. Our Commodore, Hauptmann Balthasar, has now made his 41st victory, for which he will probably receive the Oak Leaves.

This afternoon [a Sunday], a lieutenant and I from Horstkommando borrowed a pleasure boat and sailed in the fresh breeze. We had great fun, you just have to be very careful that such a big boat doesn't keel over in a strong wind..

July 3rd, 1941: Yesterday, I was at a seaside resort. At least there were more people. You should have seen the houses there; you would laugh! All of them are built very low, not one has a second story and everything is as small as toys, with all around little fences, or gardens with a few flowers in the sand. The streets with houses look like these comical half-Spanish houses that you have seen in pictures of Mexico. In general, an influence from Mexico is quite visible here. You notice this in all kinds of ways like the music, dwellings, lifestyle. For example, you will see bullfights. It's just not quite as flat as in Spain, according to the elderly matadors.

7 July 1941: Tonight, I am officer on night duty, and I sit in an office with a desk, a rug, a bunch of chairs and typewriters, telephone and cabinet. In a corner, there is my bike. It is still 35°C and I'm still sweating despite all of the easements. I have removed my tie but the thin canvas jacket is still too warm. It's 23 hours [11pm], I put some bottles on the water pipes to cool them, they are still lukewarm but nothing can be done. Today was very warm again, even though the record heat of 62°C was not beaten, thank God. I spent two hours this afternoon in the lake, then at the beach. There, the sun is not so unbearable.

If Willy really wants to fly by commercial airline, then he can happily have 50RM from me.

Yesterday, I had another wonderful excursion on our sailing yacht. It's great fun and it cools one off in this heat.

Unteroffizier Deinzer with a puppy, and wearing the white tropical helmet issued for the heat of southern France

19 July 1941: (Cherbourg-East) Yesterday, I took off from Southern France, Cazaux to Tours, 370km. Later from there to Le Havre, 240km and in the evening back to Cherbourg-East, 120km. I have lately been flying a lot through France. I was in Paris twice, and in Le Havre, Tours, Romilly, partially by train, or with my Me [Messersmitt].

July 28th, 1941: A few minutes ago, after an alarm, I had the wide expanse of the Atlantic Ocean in front of me and the Channel beneath me. Unfortunately, as so often, there was no contact with the enemy.

I saw aerial combat for the first time since getting back to the Channel front. Unfortunately, I wasn’t with my squadron, but I’m back with them again now. I’ve only been in two large-scale attacks, in

which I got into a few dogfights and came under anti-aircraft fire. Together with another plane, I flew straight into a swarm of enemy planes, where there was a lot of confusion and everybody was shooting at everybody else. I inflicted some serious damage on a Spitfire from a far distance, just as he was getting ready to shoot up one of ours. The Tommy started smoking very badly, and when I landed I could still see the splashes of oil from the Tommy machine on my own; he also splashed up the cabin of another plane of ours. The Englishman was long gone in a steep nosedive: I went after him as doggedly as I could, but I couldn't get close enough and so he escaped. But he certainly never reached home in that plane of his, because it was all shot full of holes. I didn’t have a single direct hit on my machine.

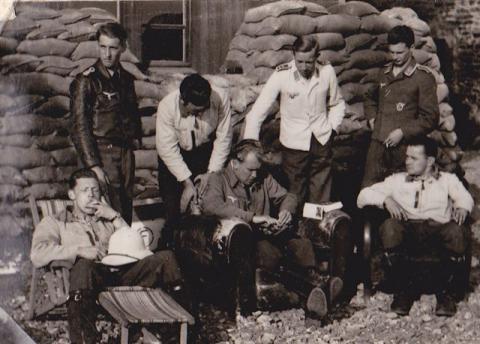

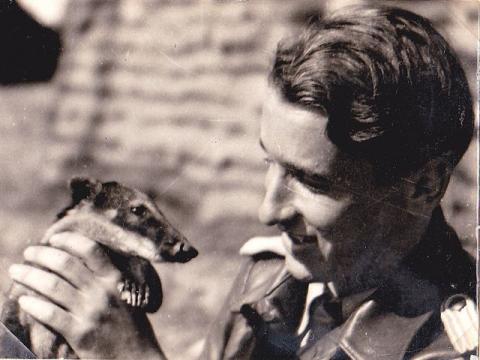

We have now got a little coati ("hog-nosed raccoon") from the Berlin Zoo. It's really fun to watch what this little fellow is doing. We also have a few dogs here now, it's a pure menagerie.

31 July 1941: This afternoon, we got quite elegant cakes and even a real torte as a snack. We have a driver who is a professional butcher, but he can bake delicious tortes with the most beautiful ornaments. The rations have become much better since the time of deployment has started. So we are all very satisfied now. If we got a few hours more sleep, we would be completely happy. We pilots moved from our castle to a corrugated steel hut [Nissan] a few kilometers away, just so that we could get more sleep instead of communing back and forth. It's not as nice out here, but while sleeping you don't realize that anyway.

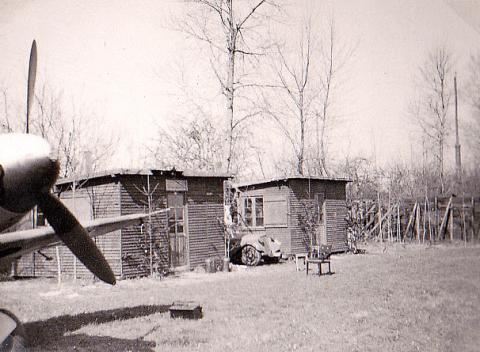

The squadron's location at Brest

"We pilots moved from our castle to a corrugated steel hut [Nissan] a few kilometers away, so we could get more sleep."

The Me 109's in readiness (Bereitschaft) at Brest, July 1941

'Poldi on standby duty at Brest in August, wearing his tropical helmet

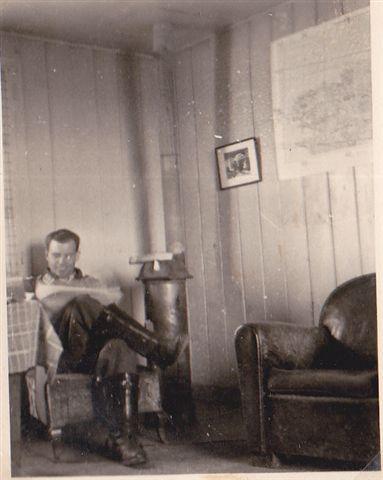

Inside the standby barrack at Brest, a pilot takes a rest

'Poldi in lifejacket, prepared to fly out over the Atlantic from Brest, 1941

22 August 1941: The day before yesterday, a few Tommies were shot down again. I flew escort for the emergency services at sea: shortly before dusk, we recovered an English lieutenant out of the Channel. He was very happy to have been saved. It was 50 kilometers off the coast, after all.

11 September 1941: Yesterday, I saw and talked to our new Commodore, Hauptmann W. Oesau. His predecessor Hauptmann Balthasar fell in aerial combat in July. Oesau now has the Oak Leaves with Swords.

Pilots of 3 Staffel; 'Poldi standing left - August '41

'Poldi plays with the squadron's pet Nassenbären (racoon)

Chassis-control check in September 1941

11 October 1941: After long and serious dental treatment - I could not fly for a long time - I am now since last Sunday back overland. I flew to Caen. I am pretty well familiar with the region by now, but a flight along the coast is still the most wonderful thing, especially around Dinard. St. Malo is terrific. And then the castle Saint Michel, standing in the middle of the lake, is an impressive sight. The same afternoon I flew back with an Me 108.

'Poldi's flyby shot of Mont St-Michal in Normandy

...and over the coastal town of St. Malo in October '41

On standby at Brest, October '41

29 November 1941: In the last days, the English attacks have strengthened somewhat. But this is good because the more Tommies come, the more Tommies go down. And so, every night a few need to come and the bombs keep missing their targets. A few days ago, for the first time, I saw a U-Boat from the inside. Looks pretty restrictive in there, inside this steel tube. Those men conducting war from in there are to be admired.

13 December 1941: Two and a half hours ago, we had an English dawn bombing attack in very bad weather. We shot down two bombers. By chance we made contact with six machines over the sea, at the same time saw a Handley-Page Hampton [British medium bomber]. Can you imagine what a scrimmage that became? We fell one after the other on the Tommy and with fast, combined attacks the rest were shot up, and then the engine was on fire. For us, it was a wonderful picture. The whole thing took place at low altitude over heavy seas. The survivors are said to have escaped by parachute. When the machine was all on fire, it reared up once again before it crashed into the water. The fuel exploded and it burned quite some time on the water surface. As it was pretty dark already, the drama offered a wonderful scene for us. First the tracer of the weapons, canons and MP's, then the flames of the burning machine and the flaming waters. A pity so many of us shot the Tommy.

We experience night attacks more often now; it's always a mighty shooting spree, and naturally you can't sleep.

End of letters from 1941-

Category

Germany, Leopold Wenger, World War IILeopold Wenger's letters from France, February - July 1942

- 3309 reads

Celebrating a victory with a champagne breakfast in Caen, July 9, 1942, left to right: Schröter, Nippa and Poldi wearing his newly awarded Iron Cross 2. (Picture taken by a war reporter) Enlarge

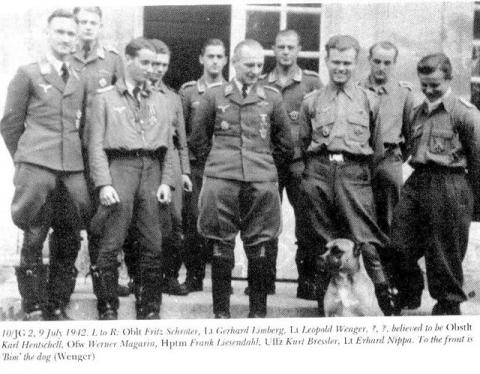

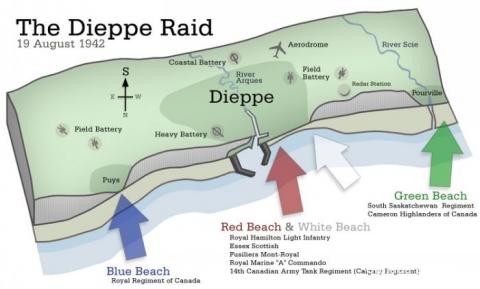

The letters from 1942 begin with Operation Cerberus, for which Leopold "Poldi" Wenger's squadron (Jagdgeschwader 2 "Richthofen") played an essential role. This is the first of two major operations in which he was to take part in 1942, the second being the Battle of Dieppe in August. In between these two, we read of continuing dog-fights over the Channel. Poldi's first letter home was not until after Cerberus was successfully completed.

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Carlos Whitlock Porter

14 February 1942: Everything has been happening at once over the past few days, as you have, of course, heard from the Christmas news bulletins; and this time we are involved, too. We flew fighter support for the German fleet and were present at precisely the most exciting moments shortly before the breakthrough at the narrowest point on the Channel and in the evening air and sea battles. It was a bold undertaking and a surprise attack right in front of the Englishmen’s own front door, so to speak, with the two battleships “Gneisenau” and “Scharnhorst”, as well as with the heavy cruiser “Prinz Eugen” and many convoy ships, torpedo boats and destroyers in the front line. [Poldi is describing Operation Cerberus that I wrote about here.]

Poldi second from left on the airfield at Katwyik, Feb. 14, 1942

At Katwyik for Operation Cerberus

When German long-range guns attempted to destroy the English coastal artillery, all the houses on the square where we were trembled, and the floors vibrated at the rumbling. This day was the first time I saw aerial combat from the ground. When we started back towards the safety of the ships, we just managed it when a British destroyer attack was defeated by our ships. There was rather misty weather and the flare of the muzzle fire from the guns was getting more and more dazzling and frightening. Once we confused two ships and found ourselves suddenly being strafed by flak from one of the British destroyers. Then the Tommies tried to blow us through the heavy use of Spitfires. That failed, too. Since we absolutely had to maintain radio silence, it wasn’t possible to communicate with each other in the normal way. For example, we could only fire tracers in front of a comrade’s [plane] to let him know that he was being attacked by one or more Brits. We protected the ships in such a way that each squadron had to fly a certain sector to prevent hostile aircraft from getting anywhere near our big ships. Most of the enemy bombers were swept away from the outer ring of our fighter squadron and we seldom even saw them with all the bad weather. It was really beautiful aerial combat.

Yesterday I flew what was up until that time my northernmost flight in the maritime territory of the Friesian Islands. In the evening we were in The Hague. That is the first time you notice the difference compared with French muddling.

In Albertville I had two days off with QBI [bad weather]. Albertville is a city of ruins, in which only the church is still standing.

Icy Leuwarden airfield, Feb. 19, 1942

Photo taken by Poldi in Leuwarden, Holland 2-19-42

19 February 1942: I’m further north now, in the vicinity of Leuwarden. So much snow and ice is something new to me, it’s the first we’ve met with this winter. So I’ve quit flying in the English Channel and I‘m flying in the North Sea now. But there’s a big difference, apart from the cold. But it won’t be long until I can fly again. We all like it better here in Holland than in France; here, you can almost speak of a second Germany. (At least compared to the usual conditions in France.) Everything is clean and neat, every house is friendly, the windows are all full of flowers, now, in the winter; even relations between soldiers and the civilian population cannot be compared with France at all.

One problem, though, is the Dutch money. Nobody can make out the guilders yet. I had a couple of hours furlough today, and was able to see the city of Leuwarden during the daytime for once. Over and over again, all I could think about was the big difference between here and “La Grande Nation".

____________________________________

Sudden furlough with the family in Leoben in early March.

Poldi on holiday with his parents in Marburg, a historic city in central Germany, March 6 ...

...where they met up with Prof. Matzl.

16 March 1942: This morning about 6 o’clock I was back in Morlaix again, a whole day too early. I couldn’t know that I would have such good connections all the way through. I was already in Linz that same afternoon and waited an hour for the commuter train from Vienna, upon which I travelled through Nuremberg and Metz to Paris, where I arrived at 6:30pm yesterday, on the 15th. My stay in Paris was also very short and I was able to travel by train direct to Morlaix the same evening, where I was happy to arrive this morning. The trains were very full!

23 March 1942: My last letter was written from Morlaix. At that time, I wanted to fly to Holland, but that was impossible due to the bad weather. So I took the train by way of Paris, Brussels, Antwerp, Rotterdam and The Hague. Then I had to wait a couple of days and was finally able to fly back to my unit (Katwijk-Leuwarden). But it was still a whole week until I was back with my comrades again. This time, I travelled by train during the day, so I was able to see something new. Yesterday we were transferred again and now, after a long time, I’m back in France where I flew for the first time (according to the flight log book: Le Havre, after a relocation flight from Leuwarden to Calais and following a layover, on to Le Havre, that is, 710 km overland).

28 March 1942 : I just received the photograph of my family, taken by the photographer Fürst in Leoben during my furlough; [it was] posed just right, but the main thing is, everybody is on there!

Everything is happening at once here. Recently, we’ve been waiting for a big offensive almost any day now. All seems very normal at night now, but, at the same time, the English have had big losses. Tonight they tried to play a trick on us. You‘ve certainly heard the special reports on this. We were happy to be able to fly a few low level attacks on them, but the Tommies got hit so bad during the night that everything was all over by the early hours of the morning, around dawn.

4 April 1942: For the moment, there’s nothing really going on here (Le Havre), so it’s really the calm before the storm. But at night there’s a lot happening. The last few nights, I was able to watch the entire air attack from my window, which gives me a good view of the whole city and the entry to the harbor. Once a bomb hit the water about a hundred meters away from me, so that I was pushed gently away from the window. But the Brits score so few hits, that it’s a shame to waste so many bombs. Most of them fall in the water.

Poldi in the "readiness seat" (Sitzbereitschaft) in Le Havre

Transfer flight to Triqueville in a Me 109 on April 10

Triqueville living barracks, April 12, 1942

11 April 1942: We’ve been transferred again [Triqueville]. Although not particularly far away (40 km), there’s the usual confusion. I’m on the left bank of the Seine now, on a small square [presumably Beaumont le Roger], in the middle of the countryside. It’s a big meadow. We live in a place seven kilometers away, with about 7,000 inhabitants, in the best hotel in the region. I don’t believe we could find a bigger hotel anywhere. We’re all glad to be out of Le Havre, since the nightly bombing attacks didn’t allow us to get any sleep. On Easter Sunday night, they dropped 12 bombs on the square without damaging anything but the grass.

Now I’m sitting in a deck chair in front of my plane and “helping them wait.” None of us can understand why the Tommies no longer come over by day. Apart from the daily combat alarms, we hardly fly any more.

It’s all wonderfully green here; we have the feeling that summer is just ahead.

19 April 1942: Today I’m sitting at my command post, on duty. I was sitting here a few days ago, when there was quite a hubbub: A large of number of incoming flights and an aerial combat, with about 150 English fighter planes and bombers... and I had to sit around down here. Today, my plane is right in front of the door and there’s really nothing going on. It’s Sunday today and the Tommies aren’t flying, after all; only a few Poles and other Legionnaires.