The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger (Part Two)

- 5899 reads

The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

Part Two - Conclusion

From the Seelow Heights—April 1945

Back Home to Leoben, Austria—July 1945

By Willy Wenger

An officer-candidate in the German Luftwaffe, Willy Wenger was only 18 in 1945 when his “odyssey” began. He is now 86. His older brother Leopold Wenger was awarded the Knight’s Cross, Germany's highest military decoration.

Translation and Introduction by Wilhelm Kriessmann

Editing by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

From April 20th onward - the final days of the Reich - 18 year old Willy Wenger was involved in the Battle for Berlin. His story continues right after receiving his first wound as he covered for German civilians trapped inside the cellar of a house. As he attempted a peek out the front door to check conditions, a Russian grenade exploded close to it. A grenade fragment struck his hand, bringing forth profuse bleeding.

For the time being we escaped hell; it was insanity what we tried to accomplish near the Sparre Platz next to a waterfront. (I still carry the grenade fragment in the ball of my left hand. I feel it only when I hit something accidentally.) We marched back to the Maikaefer barracks.

The long row of barracks on Chausseestrassee as it appeared in 1910.

I was sent to a first aid station to get properly bandaged and to receive a tetanus shot. Marching on, I was informed that it was the famous Hotel Adlon on the Unter den Linden, close to the Brandenburg Gate, where I could get help. With ruins and wreckage all around, I tried first to cross the wide Unter den Linden avenue – impossible with continual rocket fire from the Stalin Organ batteries. So I found the subway entrance and finally entered the Adlon, my first encounter with my future profession.

The luxury hotel Adlon after the Battle of Berlin

The luxury hotel Adlon after the Battle of Berlin

But what did this former luxury establishment look like? Debris all over. The floor of the great hall was covered with straw bales, wounded soldiers lay spread out. From the adjoining rooms a penetrating smell of blood and antiseptic circled the air. Doctors, nurses and medical orderlies were busy attending, all of them with tired eyes. I received my tetanus shot and the medal for wounded soldiers was handed to me, not too proud an award.

I ran into soldiers from the nearby Fuehrerbunker-headquarter. They told us Hitler and his staff were living deep underground in a bomb-secure extended bunker from where he is still giving his orders. He will remain in Berlin. There was also talk that an airplane landed at the Axis (Siegesallee) raising hopes that we might be able to leave the city. Many years after the war I read that Hanna Reitsch with Reichsmarshall Ritter von Greim landed with a small plane, stayed a few days and then returned to Rechlin. Hitler refused to leave.

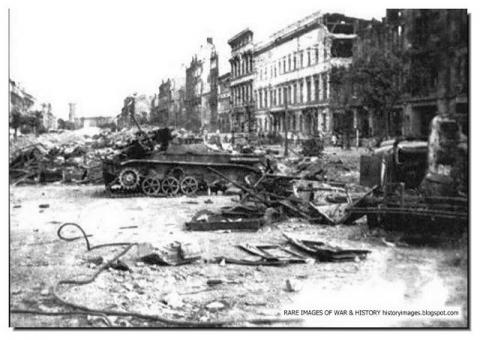

With my hand bandaged and a sling around my shoulder, I returned to the Maikaefer barrack. Immediately I was assigned to an ammunition transport - a motorbike with a sidecar. I was sitting on the back seat, the sidecar loaded with ammunition. We were driving like crazy back to our infantry. There were no clear roads anymore, just debris, rubble, dense smoke, and artillery shells howling in the air. We got entangled in utility wires hanging down from split poles.

Picture above of Under den Linden gives only an idea of the clogged nature of the streets.

Picture above of Under den Linden gives only an idea of the clogged nature of the streets.

It was ghostly, not a soul around, eyes and nose were burning from smoke and dusty air. We could hardly distinguish ruins and obstacles when, not too far ahead of us, a Russian T 34 tank turned from a side alley into our road. With no way to turn around, we drove with full speed straight toward the tank and swerved around the corner into an alley, seeing how the tank's turret swung in our direction and the canon fired. It hit the corner of the ruin – another narrow escape. The munitions were delivered on time.

With a small group, I moved from the Maikaefer barracks to the cellar of the Deutsche Theater where we stayed put. The outside was under continual Russian artillery barrage - only a few houses away the Russians were dug in. The cellar was full of civilian refugees, mostly women and a few elderly men. They warned and begged us to empty the wine cellar, they were afraid if the Russians got hold of it a terrible consequences for the women would occur. We helped ourselves with the selected treasures and obviously overdid it, a kind of end-of-the-world mood.

The 1st of May was also approaching and we had all the more reason to celebrate, believing in a miracle victory. Champagne was flowing, close to an orgy when a shrieking “hurraeae” and wild rifle shooting broke out. The Russians stormed in. Stark awake, I ran straight away through the pitch dark night and saw a glowing object rolling toward me. I thought first it was a burning cigarette, but jumped into the next house entrance. A hand grenade exploded.

I felt right away a hit in my back and the left leg. No pain but I could feel warm blood. With a large group of soldiers I moved with great difficulty from the Friedrichstrasse northwards. They laid me in a communication car, more troops joined us and, finally, two armored vehicles with guns.

We moved through the part of the city which for days had been already occupied by the Russians. Along the side of the streets and behind ruins they were dug in, shooting at us. It was severe street fighting again, with heavy losses. After hours, about 800 to 1000 men arrived in Pankow (North Berlin), among them men from the bunker who told us Hitler was dead. Years later, I read that Axmann, the Youth leader, and Bormann were amongst us, and Bormann was killed.

Martin Bormann, right, and Artur Axmann, far right

Early in the morning, still within Greater Berlin in its northwest part, our column got bogged down. Everybody was dead tired, quite a few apathetic lifeless forms sitting around, waiting, no action.

I, the wounded little corporal, forced myself up and pushed toward the head of the column. There I pleaded strongly with a ranked officer, and might even have yelled at him to take over the command. It was his duty to lead and fight us through the encirclement. There was no way back.

So we formed ourselves into a solid formation and broke though towards the Northeast, still moving through villages with Cyrillic signs – Russians living there who, surprised by our appearance, ran away in panic. By using secondary roads and trying to avoid towns and villages we managed to proceed undetected. Some young hot-heads then started shooting at distant, shadowy Russian positions and, sure enough, we right away got their answer. Our unprotected column was an easy target for the grenade launchers. A shell hit close to the radio car where I was laying between a bunch of different cables.

The driver tried to swerve around, lost control and we tumbled down a slight slope. Like in a movie in slow motion I watched how we turned around and landed upside down on the roof. The crew ran away, but I could not, entangled as I was in the mess of all the cables. I yelled for help and finally a fellow soldier got me out of the rubbery pile. I had difficulty walking but with his help reached a near-by forest.

Under hedges of dense bushes we were all hiding. I could finally change my bloody shirt and a medical orderly tried to treat my terribly hurting foot. He cut my shoe up, blood and pus oozed. The grenade fragment entered my foot between the big toe and the ball of the foot. I would not let the man touch the wound; I handled it myself with a knife, scissors and tweezers. The excruciating pain drove tears from my eyes but I succeeded, and thanks to the tetanus shot I received a few days before I did not get an infection. Exhausted, I fell into a deep sleep.

They woke me up late and it was already pitch dark. We decided to march only at night and traveled a long semi-circle in a westerly direction throughout the night. The morning breakfast: we licked the dew from the leaves of the bushes and trees. For days, we had nothing to eat or drink. We were down to a small group of about 20 men, decided upon in order to avoid the more likely detection of a large column. We dared now to march during the day, found an empty house and some food – cans of pork fat. We mixed it with rhubarb leaves and gorged it down, resulting soon in running diarrhea. Horrible.

Worse was the sight at some other desolated farm houses we passed by of brutally murdered German soldiers, mutilated just a few hours before. We were terribly shaken, checked again and again the terrain ahead of us. Our movement slowed down, partly due to my inability to march by myself. I needed help and I got it, but I felt the eyes looking at me. For a short moment I thought to take my life. They took away my rifle and the hand grenade.

An old Berliner stood up in front of me and said he did not want to walk further away from his home town and would help me. It was a sad moment when I shook hands and said good bye to all the comrades with whom I spent the last days and nights so close to disaster and death.

*

We both looked for protection, dead tired as we were, and fell asleep under dense bushes. Unreal serenity greeted us when we woke. No canon thunder, no rifle shots, burning fires or thick smoke. Flat country with no people. It was a herd of bellowing cows, their udders full of milk, that woke us, We listened to the lovely song of birds and recognized spring was here, after all the past days of horror.

Only then we noticed a farmer and his wife chasing some of the cows, trying to catch and milk them. First they were scared when they saw us in our hideaway. When we spoke hesitantly in German, they recognized our worn-out uniforms and became very friendly and helpful. “You have to get rid of your uniform, otherwise you have no chance to avoid getting caught by the Russians,” they said, and told us they would bring us civilian clothes when dusk set in.

They had two sons who were both killed on the Eastern front. We lay around the whole afternoon listening to the cows still bellowing, the longest afternoon of my life. Then there was the farmer again, pulling out of a jute sack a whole bunch of clothes and in a brown bag boiled potatoes. Heavenly thanks.

We buried all our identification, the uniform, our dog tags, our military passbook, even family photos, and started walking - my comrade from Berlin putting his arm around my shoulder, I limping. We reached a large farmhouse, the farmer allowed us to sleep between his horses overnight. The first time we had a roof above our head and no frosty shivering. The following day, May 6th, my 19th birthday!

I had slept well and felt newly born. For breakfast we got hot milk, bread and butter – what a beginning of a day. Before we left the farmer asked for my camera and explained that the Russians would confiscate it right away or even accuse me of espionage. It made sense, so sadly I handed it to him. We were civilians again, a little strange but nevertheless a nice feeling. We walked along a narrow field path, progressing slowly; my foot hurt and I could not step on it. I realized I could not continue.

A small dwelling, very isolated, literally invited us to seek rest. A farmer's wife of about 55 years invited us to come in, immediately gave us something to eat and dressed my wounds. She was very helpful, very sympathetic and reminded me of my aunt Gritzi. When she realized how desperate my condition was she would not let us leave and offered us to spend the night in the barn. We accepted thankfully.

In the next days the pain in my foot became intolerable. Pus oozed out of the cut-up shoe. I could hardly make a step; I needed a doctor. The woman told me the next available doctor would be in Oranienburg, 40km (25 miles) south. Her farmhouse was about 3 to 4km south of Löwenberg, a road junction where Neuruppin-Eberswade crosses Neubrandenburg-Berlin.

We had to march to Oranienburg, a long way ahead of us. So we bid goodbye by to the dear, helpful farmer's wife and thanked her gratefully. She repeated to us that we were welcome to come back any time if we are in trouble. But I wanted to go home and see my family; I was worrying about what might have happened to them.

At a snail's pace we marched along a wide road, an important main artery to the South.At times, my Berlin friend pulled me in a hand cart, where I could sit. Many people, mostly refugees, wandered with us. They told us that today, May 9th, the remaining German army capitulated – the war was over. Then we confronted the first Russian soldiers. We were scared but they only wanted to ask us how we were, exclaiming "nix Krieg, nix Krieg” (no war, no war), giving us some cigarettes. We were relieved and marched on, soon passing by a column of German prisoners guarded by Russian soldiers. What a pity to see them and what luck had struck us.

The entrance to Sachsenhausen concentration camp

A little bit outside the city of Oranienburg, the town of Sachsenhausen is located. There we found out that the only doctor was at the KZ Sachsenhausen, pictured above. I did not hesitate to go there since I knew a KZ was a penalty camp for criminals. We walked first through a pine tree forest amid nice villas. I later found out those were houses for the SS guard. Then a big gate, where we parted, my friend and helper now wanting to return home to Berlin. There were fences with barbed wire and, after the entrance, a long barrack with a large Red Cross sign. Relieved, I thought I would very soon see a doctor.

But it didn't happen. Several strange-looking men wearing red arm straps, who I was told later were armed civilian Polish bandits, blocked our way, and when I told them I was injured and sick they yelled, "Du nix krank, Du muessen arbeiten.” (You are not sick, you have to work).

A broom was pressed into my hand to sweep and clean the ground. From other civilians doing the same job, I was told they were grabbed on the street and forced into the camp to work. When it turned dark I was driven to the exit – free again. Since nobody was allowed to be seen outside after dark, I was afraid to be caught and get into deep trouble.

Limping into a small alley amidst villas, I entered one – it was empty. I found a soft bed and fell into a deep sleep. Next morning, I rummaged through all the drawers, found fresh underwear and could, after quite a long time, wash myself. I did not know what to do. Continuing homewards seemed to be impossible. The words of the farmer's wife entered my mind and those words gave me strength enough to make it all the way back. It was also the fear of being caught again that made me forget my pains. I found a walking stick and marched on.

When I arrived late in the afternoon at the small farmhouse the woman greeted me like a lost son. I found out that she had a close relative - nephew, or even son - with the name of Willy and maybe, for that reason, took such good care of me. I had my own room, bed, table and chair, and felt like I was in seventh heaven. For breakfast I had real coffee with an egg since she had no milk. Lots of chickens but no cattle. She grew plenty of asparagus, which was unknown to me, but now very appreciated for its various dishes – soup and omelet and as salad with mayonnaise.

I thought I was living in the land of milk and honey. I helped her with daily chores as well as I could and was happy as a lark. Gradually my wounds healed. My foot and hand showed scars, but I could move around fairly well.

For over a month Elswitha - that was her name - took care of me. But I got restless wondering what was going on back home, thinking what the future held. We were completely cut off from the outside world - no radio, no newspapers. From time to time people from Berlin found our farm house, trying to exchange some of their "goodies" for eggs and vegetables. Some of those visitors told me the Ostmark was now Austria again, and that my homeland, Styria, was occupied by the Soviets. They also told me Berlin and the rest of Germany was divided into four zones.

Were my parents alive? Where was my older brother, fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe? Plans circulated through my brain; maps and traveling routes were tossed around. My desire to return grew stronger and my female protector knew that the time would come when I would have to leave. I thought I should try to reach the US zone in Berlin and from there somehow get to Bavaria and from there to Austria. It was known that the Russians very often snatched young people without any special reason and forced them to accompany the cattle transports headed back East.

Luck then helped me with my further planning. Two women from the mayor's office of the village of Loewenburg visited Elswitha and, when they heard I was going to try to return to Austria, they offered me an identification pass. A few days later they returned and, sure enough, they handed me a paper which was of immense help later on. On a half page the following text was typed:

CERTIFICATION

Mr. Wilhelm Wenger, born May 6, 1926, in Anger, Austria, was drafted to render important war services in the town of Löwenburg. He was hard-working and did his job properly. There is no objection to his return to Austria. Kindly help Mr. Wenger as much as possible to return to his homeland.

Signed, Mayor of Löwenburg (carrying the office stamp)

It was not easy to leave. She treated me as her son as she nursed me back to health and now I was leaving. We both had tears in our eyes as I bid her goodbye. She put a large food package and a shirt into my rucksack. I gripped my walking stick and, slightly hobbling, I walked on. One last time I turned around, seeing the little farmhouse disappear behind the group of willow trees.

Pretty soon I reached the main road South. I walked through Oranienburg and Sachsenhausen and arrived dead tired at the edge of Berlin, in Tegel. (Note that Seelow is east of Berlin close to the Oder River. Willy is back where he began. Click to enlarge) I was surprised when a young, well-attired man addressed me, asking if I were a former soldier on my way home. He introduced himself as a Lutheran priest helping homeward-bound soldiers. At a small villa, I met a lot of other ex-soldiers; we were fed, slept in a bed and next morning we could even take a shower bath. A hearty breakfast and some pocket money were handed out and, with a goodbye, we were sent on our further way. Indeed, a very unusual treatment.

Pretty soon I reached the main road South. I walked through Oranienburg and Sachsenhausen and arrived dead tired at the edge of Berlin, in Tegel. (Note that Seelow is east of Berlin close to the Oder River. Willy is back where he began. Click to enlarge) I was surprised when a young, well-attired man addressed me, asking if I were a former soldier on my way home. He introduced himself as a Lutheran priest helping homeward-bound soldiers. At a small villa, I met a lot of other ex-soldiers; we were fed, slept in a bed and next morning we could even take a shower bath. A hearty breakfast and some pocket money were handed out and, with a goodbye, we were sent on our further way. Indeed, a very unusual treatment.

I received detailed information on how to find my way to the South end of Berlin, and thought to visit the Deutsche Theater where I found such good company in April. I had to turn away in a hurry when I noticed Russian soldiers at the entrance. Walking through ruins and debris, I came to the railway station of Lichterfelde-Ost at the South end of Berlin. The hall was crowded but I found a patch of straw on which I could lay down for sleep.

Early in the morning, everyone pushed to get a place in the rail cars. We passed through Jüterbog, which I had marched through two month ago, and arrived in Wittenberg on the Elbe river. (click to enlarge map) I tried to cross the river over the bridge but the Russian border guard drove me back. My idea to reach the West through the U.S. zone to Bavaria failed. Some of us were thinking to swim across the Elbe river, but gave up the idea when we were told the Russians were cold-bloodedly shooting at everybody who tried.

Early in the morning, everyone pushed to get a place in the rail cars. We passed through Jüterbog, which I had marched through two month ago, and arrived in Wittenberg on the Elbe river. (click to enlarge map) I tried to cross the river over the bridge but the Russian border guard drove me back. My idea to reach the West through the U.S. zone to Bavaria failed. Some of us were thinking to swim across the Elbe river, but gave up the idea when we were told the Russians were cold-bloodedly shooting at everybody who tried.

I joined a small group of refugees and we marched for quite a time southwards. At a small village I went to the mayor's office to find out which route we should take. Bread was distributed. I received half a loaf and got signature and stamp on my identity paper. Overnight, a mixed crowd of women, children and men slept in a large school gym. Our morning toilette was very primitive. Again, a long, tiring foot march and we reached the city Riesa on the Elbe river.

Someone suggested to try a steamship trip; we saw a boat on a landing stage and managed to get on board amid a hard-pushing crowd. In the distance we recognized the silhouettes of Dresden and by the dimming light of the early evening we made out the contours of some of the well-known buildings. How terrible then was the view when we approached the waterfront.

Not one house or building was intact. It was ruins everywhere, and piles of rubbish – a depressing scene of devastation. We lost our orientation because former streets were narrowed to paths of small roads edged on both sides by piles of stones, wire and wood. We hurried along and just guessed our direction towards the South. We were now a small group of Austrians, closely bound together by our decision to make our way to Austria through the former protectorate, Bohemia-Moravia. It was now the new Czech Republic and we were uncertain what was waiting for us there.

We were hungry and tired when we boarded the overloaded train and in a while crossed the border. We noticed that the Czech passengers looked at us with deep suspicion. We were all wearing red-white-red patches on our jackets and held on to our papers identifying us as Austrians. When we could not answer their questions in Czech, most of them addressed us in German.

A flood of terrible tales poured over us. They were eager to let us know how they treated German civilians, their neighbors, and German soldiers without their weapons. They demanded our attention as to how they threw people into the Elbe river, nailed them on rafts and burned them, buried German soldiers alive after they clobbered them to cripples. Deeply shocked, we were quiet, did not utter a word and were relieved when we arrived at Leitmeritz/Litomerice and had to get off the train.

We were directed to a freight train and told it was on the way to Vienna. The cars were dirty and full of coal dust. I got very suspicious and, sure enough, after the train left, somebody yelled, “It is going to Poland.” When the train slowed climbing up a hill, I and a friend from my home area, Bruck, jumped off the train. It was pitch dark, I rolled down a hill, did not hurt myself and found my comrade also unhurt. We walked back to the train station and in the morning boarded a train to Prague. Sheer luck. At Prague, we had to leave the train again and found out that in a few hours a train will depart for Vienna. We walked through the city and were surprised to see streets and houses intact, no ruins at all and plenty of goods in the stores, like a fairy tale. But it did not help us.

Hungry, we returned to the station. Terrified, we recognized that the entrance was cordoned off by military police and everybody was checked. I had lots of trouble convincing them that I was an Austrian returning from work in Germany and not a Hitler Youth or soldier. My paper with the stamps and signatures were finally a help to me. They turned my rucksack upside down, but luckily my watch that was hidden there did not fall out. My comrade from Bruck also passed.

We found the train to Bruenn but we did not find any room inside and so climbed like many others onto the roof. There, we did not have to listen to the horrible talk but we got some bruises on our head and shoulders when hit by the wires hanging down from bridges we passed under. Right next to me sat a Russian soldier with his automatic rifle across his legs, trying to talk to me. By gestures and finger-pointing we finally understood each other. He also spoke some German. He was rather friendly to us, however he disliked the Czechs very much.

When we stopped at a station he asked me take care of his weapon; he wanted to get a drink of water. He left the gun on my lap. The Czechs looked hatefully at me and I was afraid something might happen. With a friendly smile, the soldier returned and sat down by my side as if nothing happened. Did he want to humiliate the Czechs?

During the afternoon we arrived at the central station of Bruenn. I tried to join a line in front of a Red Cross station to get something to eat. Hateful voices yelled at me, "Deutsche, Raus” (get out, you Germans), pushed me away and threatened me. A Red Cross nurse grabbed my hand and gave me a bowl of soup and a slice of bread – never did a meal taste better.

A local train took us to the border. As dusk set in, we walked to the border line. The customs-and-transfer station was closed. We were informed that after dark an absolute lockout was ordered; we were afraid to be shot at if we moved and looked for shelter. So we – about 30 people – camped right there on the meadow next door to the customs house. Czech officials tried to drive us away but we stubbornly laid down and would not move.

Hardly any one slept and restlessly we waited for the dawn, looked over the crossbeam to the dear homeland only a few feet away. Finally, after hours, the ugly beam was lifted; we ran across, threw our arms around each other and cried, “Home!” Suddenly a Russian soldier approached us with his Kalashnikov raised, shouting "Dokumenti, Dokumenti." I pulled my paper out, he turned it around and when he noticed the many stamps and signatures, I could pass.

We marched on and were lead to a big building where we received a hearty breakfast and then had to register and check out lists of refugees, to eventually find friends or family. Overwhelmed and carried away with emotion, I could not wait for a train which was supposed to arrive in a few hours. I took my walking stick and arrived shortly before noontime at Gaenserndorf.

I was hungry and needed help. I found the mayor's office adorned by a Soviet star – Communist rule? I entered and introduced myself as an ex-soldier. They were very friendly and handed me a loaf of bread. Gratefully, I turned around, clicked my heels, raised my hand in "Heil Hitler." Right away realizing my mistake, I could have sunk into the floor – but they laughed and I rushed out and hurried up the road.

There seemed to be no end to the Marchfeld when I walked towards Vienna and reached the Danube. No bridge led across the river, two were destroyed. A local told me to march further on northwards and I would be able to climb over the broken pillars and cement blocks of a half-damaged bridge.

It was dark when I reached the west bank of the Danube. The streets were empty, a curfew was obviously established, but I still walked on, hiding behind corners when military guards approached. I knew where my Aunt Mitzi and Uncle Karl lived – it must have been past midnight when I pushed through the entrance door and awakened my relatives. They stared at me half-awake, recognized who I was and embraced me dearly.

Next morning, my uncle and I climbed into a crowded train at the Suedbahnhof that was going to Graz. In Bruck a Mur we departed the train; my uncle went on to Bad Gleichenberg to find out if his garden house survived the war, and I boarded the train to Leoben. I was nervously excited, everything went too slow. When I crossed the Mur bridge on foot my knees shook. I waved when I saw the windows of our apartment on the second floor and my mother looking out. She recognized me.

What tremendous joy, a deep, emotional embrace, what heavy tears and sobs. My sister had grown up, my 6-year old brother Gerhard did not recognize me. There was joy all around, but one bitter pill – we did not know where my older brother was.

My odyssey was over, my future very uncertain.

END - Back to Part One