The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

Exclusive at carolynyeager.net! This is the never-before-published true story of a young German soldier thrown into the battle of Seelow Heights in the last month of the Second World War—how he survived against all odds and managed to return home.

The Odyssey of Fahnenjunker Wenger

From the Seelow Heights—April 1945

Back Home to Leoben, Austria—July 1945

By Willy Wenger

An officer-candidate in the German Luftwaffe, Willy Wenger was only 18 in 1945 when his “odyssey” began. He is now 86. His older brother Leopold Wenger was awarded the Knight’s Cross, Germany's highest military decoration.

Translation and Introduction by Wilhelm Kriessmann

Editing by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

For the 17-year-old high school student Willy Wenger, his brother "Poldi," squadron leader at SG10 of the German Luftwaffe, was an outstanding role model. Willy wanted to follow in the footsteps of this highly decorated Jabo* pilot, who was five years older than himself. In July 1942, Willy received his C license for glider pilots (pictured at right on glider) and in April 1943 at the Reichssegelflugschule Spitzerberg near Vienna, he earned the Luftfahrerschein (air pilot pass). (See picture below)

[*Jagdbomber: fighter-bomber ]

The war situation in the spring of 1943 made it necessary to call up the final classes of high school students to the services of the Home Anti-Aircraft Forces, or FLAK. Wenger’s high school class assembled at barracks within the steel plant of the Herman Goering Werke (later named Voest-Alpine) at Linz/Donau. School lessons continued but the young pupils also had to learn how to handle the 3.7cm anti-aircraft guns and all the additional equipment.

Above: Wenger earns his basic pilot's license in 1943 at the flying school at Spitzerberg.

Because of injuries at gun practices, Willy was able to spend a furlough at home in Leoben at the same time his older brother Leopold, the Luftwaffen pilot, also arrived back home for a short leave.

Turbulent months followed his return from his New Year furlough to his FLAK unit in Linz. Only a few weeks after the class returned to the school in Maburg and report cards were issued, Wenger was called to the service at the RAD (Reichs Arbeits Dienst), Reichs Labor Service, an obligatory three-month draft. During the three very cold winter months of 1944, the RAD men were working on a railway ramp to connect the main line with a trunk line to a large armament plant in Silesia. Basic boot camp training was still part of their activities, however. (Right: Willy is in center of group) In early May, Wenger was back at school in his last year but, as it turned out, only for a few weeks. There were merry reunions, parties and dancing and when the call for military service came, Wenger volunteered to be an officer candidate in the Luftwaffe.

On July 6, 1944, he arrived at the Kriegsschule 3 at Oschatz, in the state of Saxonia. As a Fahnenjunker (cadet), he was looking forward to becoming a pilot like his brother.

That dream ended when Reichsmarschall Göring ordered 100,000 Luftwaffen personnel to fill the gaps suffered by the German army. In early spring 1945 Fahnenjunker Wenger, now Fallschirmjaeger (parachute trooper), was on the way to the Eastern front some 80km distance from Berlin.

We now let him tell his story:

I was literally thrown out of the luggage netting where I had just found space to take a nap. A screeching, breaking noise and then a sudden stop. Mixed into it was the terrible howling sound of numerous sirens - horror music like a multiple echo swept across the area. Though experienced by the civilian population for years, it had luckily been unknown to me up until now. It was late March 1945 when we entered Berlin by train.

I had never experienced any air attacks before. Not in Marburg, where I attended high school in the summer of 1943 and lived with Aunt Hilda in her big house. As soon as I left, a bomb hit the house and demolished part of it. Straight from the high school in Marburg we were drafted into the Flak. In Linz, we Hitler Youth became anti-aircraft gunners.

I arrived with a train transport at a location close to Berlin where we had to run away from the train because all hell broke loose. Sirens were howling gruesomely from all directions, accompanied by the engine noise of hundreds of bomber airplanes approaching the city. Searchlights cast their rays into the sky and caught an aircraft from time to time. Soon darkness turned into bright light as burning "Christmas trees" floated from the sky, marking the targets. They were dropped by the enemy pathfinder airplanes.

I ran into a field and tried to dig a protective hole into the frozen soil with my empty canteen but without much success. When scared to death, one develops super strength. Then the bombs dropped like a carpet over the city, some close to us. We jumped up and down thinking to be torn to pieces any minute; the pressure of the explosions seems to destroy the eardrums.

Even though the attack lasted only minutes it felt like an eternity. Then, as the engine noise simmered away and only sporadic anti-aircraft gun fire occurred, one could see the ghostly remains of the vast housing complexes lit by an immense blaze. I never imagined my first encounter with the capital of the Reich would be like this!

Finally, our train arrived at the railway station of a suburb. Something very touching happened. One of our comrades noticed his mother on an arriving train. He waved and yelled; his mother came over, stayed with him a few hours and drove with us to the next station where she departed with tears in her eyes.

Well, here I was now, a Fallschirmjaeger wearing that odd, coat-like, long uniform jacket and the special helmet – so different from the infantry helmets – with flattened edges to avoid air resistance when jumping. The Inside was cushioned with heavy rubber pads. A parachute, however, I did not carry.

As a glider pilot at the Reichssegelfliegerschule Spitzerberg I always carried a parachute but never used it; never jumped. Only much later, in 1977 in North Africa, I jumped out of curiosity and hurt one of my vertebrae. As a result, I still have trouble turning my head properly.

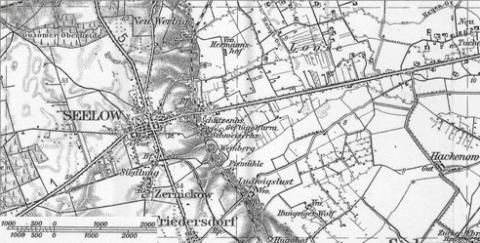

I did not know which city parts of Berlin we marched through but the general direction was North. They said Stettin was our target . We took our first rest at a very idyllic recreation spot, a forest next to a lake in the vicinity of the city of Finsterwalde. I remember the place because I mailed a parcel from there to my parents. They never got it. We drove towards Angermuende and received the order to turn southward, parallel to the Oder river, until we reached a small village, Seelow, west of Kuestrin. There we disembarked.

The Seelow Heights overlook the Oderbruch, the western flood plain of the Oder River which is a further 20km to the east.

Near a small farmhouse, we occupied an already pre-built large trench system. I was now a member of a Sturm-Zug (attack troop) at a parachute troop unit. All of us were youngsters, none over 25 years old. Our troop leader, a young lieutenant just a few years older than us but already an old timer, told us that we had been selected to attack the enemy even if all others retreat. We were kind of proud to hear this.

At the corner of the farm house I saw a row of shoes covered by canvas, with only the toes protruding. A soldier explained they were dead German soldiers, killed last night when they tried to break out of a Russian encirclement and were hit by our own artillery which thought the Russians were attacking. Never before had I seen a dead person and was afraid to look at death, and did not therefore help to put them to rest.

At this time of the year it was still very cold and at night we were really near freezing. I had to share a small foxhole with my comrade. This was our living quarter where we stored our belongings and weapons and where we slept. Pressed together, we lay there on straw, protected on top by two logs covered with soil … pretty crummy.

Now I was a combat soldier, fulfilling my duty, holding the attack rifle in my hands and carrying the hand grenades around my hip, trotting through the wide system of trenches and being mighty proud. Even as the first artillery shells hit closer it was an adventurous happening. But when the shells hit closer and closer, my heroism disappeared rather fast and I anxiously ran for cover. I was terribly scared.

We crouched in the trenches and waited and waited – sometimes the Russian artillery decked us pretty good. The first wounded yelled, the first blood ran, and I was afraid I would lose consciousness. I tried to hold on to something but then realized I had to help and I regained strength and was not afraid. That Will helped me for the rest of the war, never again did I collapse.

At the East bank of the Oder River the Russians had concentrated strong forces close to the damaged bridges during the last few days, ready for the crossing. We saw several Ju 88 bombers, protected by fighter planes, flying over our trenches. Mounted on top of their wings were FW 190 fighter planes steering the 88's loaded with detonation material into a steep dive down onto the Russian concentration. [Willy was seeing the "Mistel" composite aircraft, pictured at left. The name came from the German "Mistletoe." It was also called Beethoven's Device and Daddy and Son.-cy]

All hell broke out, the Russian flak fired out of all their barrels, we could see red flaming grenades flying into the sky (we called it the tomato flak). Black clouds formed by the exploding shells crowded the sky. When the heavy bomber planes hit the ground the strong Russian anti-aircraft defense was suddenly silenced. Heavy smoke columns raised skywards. Shortly before the attack, Hermann Goering, the Reichsmarschall, passed by our trenches to watch the air attack of his Luftwaffen pilots.

For quite a while after these Luftwaffen attacks our front line was rather calm. We all knew it was the silence before the storm. Our daily food supply got worse – an old soldier delivered it on a broken down carriage drawn by an old, half starved horse. It consisted mainly of bread and milk, over-cooked potatoes, and pudding powder without any sugar. The so-called cook had no idea what he was doing; he was holding the job in order to avoid Front service. When he was supposed to bake bread with flour, which he said he found at a desolated farm house, it was gypsum powder that he mixed. That's what we had to live on.

There was not much shooting going on. Everyday Russian reconnaissance airplanes circled above our front line dropping leaflets asking us to surrender. The air traffic increased at night when a small airplane – its engine sounded like a sawing machine – dropped bombs which missed but the noise kept us awake. Sleep was very light and rare, we all were under severe tension. The Russians succeeded in crossing the Oder River at Kuestrin and had a bridgehead at the Western bank. Masses of troops flooded the area with tanks and artillery.

In the early hours of April 16, 1945, a massive 2200 cannon artillery barrage began and literally tossed every square meter of the German defense line.

Devastating was the howling noise of the Russian rocket artillery, the Stalin Organs (pictured above). You could hear the regular artillery shells buzzing in but the rockets hit like a sudden lightning. This heavy barrage lasted nearly three hours. Russian airplanes dropped their bomb carpets on our defenses. Finally at 6:55 the Soviet infantry attacked. Horizontal searchlights ghostily illuminated the battlefield, blinding friend and foe; dense fog increased the turbulence. Total chaos reigned.

We could hear but not see the fearsome rattling noise of thousands of Russian tank wheel-chains and, likewise, could only hear the echo of the gruesome yells of the storming Russian infantry. We were scared to death. The moment arrived when we wanted to leave and run away from our trenches but it turned out that we ran in circles. We lost our orientation completely and arrived at a small bridge which we had seen only shortly before. We were running in the midst of Russian infantry and tanks that were visible only as shadows – a total confusion. The time between the artillery barrage and the attack seemed like eternity.

The anxiety one experiences in such a situation is indescribable. Closely pressed to each other, my comrade and I lay in the foxhole and felt the slightest shivering of our bodies. We started to pray and expected to be hit any moment and were then surprised to still be alive. By that bombardment of shells and rockets not one inch of the terrain remained untouched. Thank God we did not stay at the same spot but ran panicky for coverage.

After running around for several hours I found my platoon leader, the young lieutenant. He also looked rather distraught and felt sorry that we inexperienced soldiers had to go through such a traumatic experience. Most of our comrades we could not find. They probably did not survive the vehement Russian attack. I found out that my foxhole neighbor was seriously wounded and lost an eye.

We had to retreat westward. On the way we ran into a SS unit; they ordered us to counter attack. We were bunched together, no one knew each other but we moved forward – such a diverse unit – and all of a sudden found ourselves marching through dense fog between Russian forces. Desperate, we dug ourselves in on top of a small hill. All was frighteningly quiet around us. We were exhausted and dog tired.

That was the moment for us to beat back the enemy. We started our counterattack and stormed forward. Horrible was the smell of burned human flesh in the destroyed tanks as we closed in. Tremendous smoke clouds rose into the sky, shrieking battle noise all around, and the thousand-fold “hurraehh” roar of the attacking Russians. It was hell!

Right in front of me a Russian soldier suddenly sprang out of a bush, his rifle directed at me. It was the only time in my life that I was forced to aim and shoot at a human being in order to save my life. I certainly had my jitters and trembled. The Russian probably also. Both shots discharged nearly at the same time, both missed and we both ran in opposite directions into protective bushes. I still remember very well that I lost the reserve bullet magazine of my assault rifle, ran back and picked it up. Afterward I thought how dumb I was to run back and expose myself to the enemy. They could have killed me.

We retreated again, better said, we ran to save our lives – behind us the gigantic mass of attacking Russians. It is impossible to describe the situation. We reached Muencheberg. I always remember the event there. During a short pause in the fighting I ran into some comrades who were separated from our unit. I was very angry about the SS fellows ordering us to that senseless attack while they retreated. I turned pale when, turning around, I looked into the eyes of a tall SS man in uniform. But he agreed, and joined us and stayed with us all the way through the final Berlin battle. He was a Berliner and a very reliable comrade.

Chaos and confusion all around. One could not find his comrades anymore. From time to time we were controlled by the military police, called “chain dogs” (Kettenhunde) because they wore a small metal shield on a chain around their neck. They were looking for deserters or stray soldiers, thus not too popular with the common soldier.

On April 20, 1945, Adolf's 56th birthday, one of the fellows said "Today Adolf is celebrating his last birthday," a remark he would not have dared make a few weeks earlier. At a shelter in the woods we listened to Dr. Goebbels’ speech, calming and inspiring us, about new miracle weapons that would reinforce our forces. We had no idea what was happening; what the situation was. We did not know that the American Army was already deep into Germany and approaching from southwest of Berlin. New hope bubbled up. But ten days later Hitler was dead and the Third Reich destroyed.

* * *

When the Russian offensive began, Marshal Zhukov addressed his troops:

"Soviet soldiers, take revenge in a way that the invasion of our armies is remembered not only by the present German generation but by their descendants in the distant future. Remember also that everything the German sub-humans owned belongs to you. Soviet soldier, have no mercy in your heart."

Every German soldier now had to face such slogans. He was thinking about the uncertain future—what will happen? Apathy took over and the only thought became survival. Gone was our idealism, our belief in the just cause, and our enthusiasm – but still we wanted to defend our homeland. In panic, everyone moved westward – masses of soldiers but also civilian refugees, women and children moved through the Brandenburg landscape. By foot or with horse-drawn wagons or pushing their own carriages, while behind, the thunder of guns in between shell explosions, detonations, smoke, dust and the approaching shrill “hurraehh” of the Soviet infantry.

We gathered again on top of a hill, a group of stray soldiers which my lieutenant and I ordered into trenches to set up a defense line. We were both surveying the area when all of a sudden whistling shells exploded around us . A Russian rocket hit. I heard the cry of the lieutenant, "Wenger, I got hit, help please."

We were close to a farmhouse and I was able to find a two-wheel carriage upon which I loaded the wounded man and pushed and pulled, as it seems for hours, until I reached a field emergency hospital. Hundreds of wounded German soldiers were being treated, most laying on the bare ground, and the doctors operating on tables in the open air. A pitiful scene, filled with blood and misery. They clung to my arms and legs and cried out for help but I had to march on with the troop of lost soldiers westward towards Berlin.

Shortly before Koepenick we were lucky again when a series of Russian artillery shells hit a mighty tree on a hillside where we had intended to rest, but moved away when I warned my comrades. I am not superstitious but when I found a horseshoe on the first day of the Russian offensive, and looked for one and found it everyday from then on, I considered it my lucky charm. At Neukoelln, we reached the city edge of Berlin. Tired as we were, we dragged ourselves through the empty streets towards the railway station, just in time to meet an arriving food supply train. We received our special rations, and, in addition, I got a big margarine cube which a little later I gave away to a young woman with her child.

We were now in the capital of the Reich at its eastern part, ruins and rubble all around – apartment caves, barricaded windows, stove pipes like black fingers sticking out into the cold air. When we marched through Koepenick I smiled bitterly, remembering the comedy of the “Hauptmann (Captain) of Koepenick.”

It was dark when we reached the Teltower canal and entered a factory hall full of iron ingots and half-fabricated tools to find our night quarters. There we established our new defense line and I, an 18-year old youngster, was now in charge of a platoon of members of the Volkssturm (people's militia); most of the men could have been my grandfathers. They asked me awkward questions, like 'how to handle a Panzerfaust?' (bazooka) which I had never handled myself. It was very hard for me to keep their confidence.

Late in the evening a small troop returned from a reconnaissance tour loaded with cartons of chocolate. Across the Teltower canal they had found the well-known Sarotti chocolate factory, completely desolated, and took whatever they could carry. The Russians were already close to the Tempelhof airfield.

It was pitch dark when I stepped out to investigate our immediate neighborhood, finally having a chance to munch on my provisions. As I cautiously approached a bridge that I wanted to cross, with the thundering sound of Russian artillery bombarding Tempelhof, a tremendous blast suddenly occurred. My little food parcel flew into the air, I lost the bite I had just taken and struggled to the ground. The bridge was not there anymore; German pioneers had set the explosives. Shattered, I returned to the factory and now helped myself to the Sarotti chocolate; the biting hunger was soon gone.

A young NCO from Vienna who had joined our troop always walked around with his automatic MP slung around his shoulder and the unavoidable happened. He tripped, his gun hit the hard floor, a shot discharged and hit him in the stomach. The poor fellow yelled, roared like an animal, beat with hands and legs around him. I can still hear the terror cries, but don't know if he survived.

We move on toward the center of the city, the Russians close behind us. We were told to take whatever we can from the warehouses before the Russians arrive. So, whole butter barrels were dropped from the Karhaus department store. Never in my life had I had such thick butter sandwiches. On the way we found our SS man again; he had gotten lost and was involved in some street fighting. His head was so wrapped in bandages he looked like an Indian. A Russian prisoner carried his ammunition belts and together we marched and reached the S station Gesundbrunnen and the Humboldt Hainpark.

Two giant flak towers loomed into the sky – one of them became our new quarter. Finally, we could rest on mattresses and soon fell into deep sleep. The Russian prisoner tried to run away, was shot and buried right there. (Right: View of the Humboldthain Flak Towers in Berlin as they stand today.)

We spent about two days in the bunker, exhausted, losing any contact with the outside world. No gunfire, no smoke, no roaring . The thick cement wall kept everything away. But it was quietness before the storm. We marched out and were surprised by a heavy air raid – the sirens did not work any more. I ran into the cellar of an apartment house when the bombs hit. Walls and ceilings tumbled down, dust, smoke and darkness surrounded me. I was buried and lost the orientation but could hear muffled yells. Digging and crawling I finally found an opening excavated from outside. What a relief! Dusty and dirty and blue spots all over but otherwise okay – I survived.

Again we were astray, our unit did not exist anymore and we were directed to gather at the Maikaefer-kaserne (barracks) at the Chauseestrasse, the battle post of our parachute division. We arrived and bivouacked at its spread-out grounds. Pretty soon an alarm came; a police officer reported the approach of a Russian tank and requested volunteers for a counterattack with Panzerfaust Bazooka (Picture below left, a volksturm man with a panzerfaust). I thought I had to join even though I had no idea how to handle a Panzerfaust and, sure enough, I nearly killed myself when I tried to discharge it with my back close to a stone wall.

The officer called me back. We crawled across a yard into a small house and were supposed to occupy a better position in the nearby building block. I considered that plan insane but had to follow orders. Under heavy Russian MG fire from three sides, we had to storm the house, now positioned between the two front lines. Behind us the German Police unit protected us with their gunfire, in front of us the Russians shot at us wildly.

From the cellar of the house a few women ran towards us, threw their arms around our neck, kissed and cried and demanded that we enter the cellar to witness some horrible crimes. I tried hard to avoid that; the Russians could throw a hand grenade into the cellar and all of us would have been killed. The Russians were only a few meters away, shooting like crazy and throwing hand grenades. They wanted to retake the house. I covered from behind the front door and when I dared for a quick look out, sure enough I got hit.

A fiery flash, a strong detonation, I felt something strike my hand and immediately blood ran profusely. A Russian hand grenade exploded close to the door.

To be continued. End of part one.

Category

Germany, Willy Wenger, World War II- Printer-friendly version

- 6055 reads