Elie Wiesel and the Mossad, Part 2

by Carolyn Yeager, February 2011

copyright 2011 Carolyn Yeager

The activities of the Irgun dominate Wiesel’s life and attention in 1948.

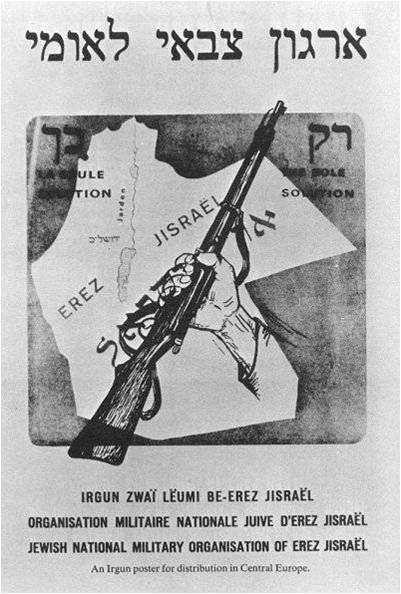

This propaganda poster, with the Hebrew words “This Way Only” on the artwork, was for distribution in central Europe. It was designed in 1937 by the wife of a Polish reserve officer who was working with Irgun representatives. [See story below: Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe] The entire area was called Eretz Israel and was claimed for a future Jewish state.

Dear Readers, As it has turned out, there is much to relate about this one year of 1948 before we get to Elie’s travels. Therefore, I ask for your patience once again. When we left off in Part I, he had just gone to work for the Irgun newspaper, Zion in Kamf. It was November 1947. Here is how he describes his vision of the underground “resistance” at this time.

Physical courage, self-sacrifice, and solidarity could be found even in the lower depths; total compassion, rejection of humiliation either suffered or imposed, and altruism in the absolute sense were found only among those who fought for an idea and an ideal that went beyond themselves. Nobility of action was found only among those who espoused the cause of the weak and oppressed, the prisoners of evil and misfortune. 5

Strangely, this sounds like the “ideas and ideals” of the National Socialists in Germany in the 1920’s who sought the way to lift themselves out of the humiliation and extreme economic hardship imposed on them by the Versailles dictate. But to young Wiesel, the only suffering worth seeing or talking about was that of the Jews. He had not a thought or concern about the native people in Palestine and what was happening to them, just as the Jews of the previous inter-war generation had no concern for the Germans they were exploiting. These others, for him, could not be seen as the “weak and oppressed,” but only as the new enemy that must be overcome by whatever methods were necessary. To Wiesel, even in his youth, only the Jewish militant fighters were “noble” when they carried out their tough and “necessary” actions.

Wiesel admits that by going to work for the Irgun in Paris he was: “risking neither death nor imprisonment. Even deportation from France was unlikely. Stateless persons were rarely deported, that was one of the few advantages of the status.” (Rivers, p162)

This again brings up the question of why Wiesel didn’t seek to become a French national. His sister Hilda had done so. Could it be that his underworld advisors were keeping open where he would be most useful? And as he himself said, being stateless had its advantages – useful for someone working on the fringes of illegality. Here’s how he describes his introduction to the Irgun.

The following Monday I presented myself at the editorial office. Joseph, the boss, showed me to a desk, handed me an article in Hebrew, and asked me to translate it. The article, published in the Irgun’s newspaper in Israel, was a denunciation of David Ben-Gurion and the Haganah and a paean to Menachem Begin, commander in chief of the Irgun. I translated the Hebrew words into Yiddish without grasping their meaning. I knew that the Haganah was fighting the British as hard as the Irgun was, and I couldn’t understand why the two movements hated each other so much. The article also mentioned the Lehi (the so-called Stern Gang), but what was its role? [p163]

I don’t think, after having two “best friends” working for the “resistance” [Francois and Kalman] and reading everything in the newspapers about the events in Palestine during the past year or two, that Wiesel is being entirely honest when expressing such naivete about the disputing militant factions. Continuing:

The article talked about a certain “season” during which atrocious acts were allegedly committed by the Jewish political establishment. I didn’t dare ask Joseph about this.

“I didn’t dare” brings to mind another passage he wrote on pages 229-30 describing a visit to his sister Bea in Canada. “I desperately wanted to ask her a question that had haunted me for years. What was it like before the selection, those final moments, that last walk with Mother and Tsipouka? It was the same with Hilda. I didn’t dare.”

May I suggest “I didn’t dare” is cover for the real reason—he doesn’t want an answer so that he will not know. And they – Bea, Hilda and Joseph - will be released from telling him something he will have to forget, or lie about. By not daring to know, he can remain blissfully naive about things that “happened, but weren’t real.” Or, were real but never happened.

Oddly, Wiesel’s mystic-mentor Shushani was also caught up in the Jewish assaults in Palestine:

Though he abhorred violence, he was hardly indifferent to the Jewish struggle in Palestine. Whenever the British arrested a member of an underground organization, Shushani tried to get information about his fate. One day he seemed extremely agitated. He interrupted our lesson, pacing, bumping into walls, blowing his nose, panting and wiping his forehead … It was the day a member of the Lehi and a member of the Irgun committed suicide together just a few hours before their scheduled execution. [p164]

I have had the suspicion that Shushani—the expert on the mysteries of life, the illumined one—also had connections to the Zionist intelligence network. Here we learn from Wiesel that he was so partial to the Jew’s fortunes in Palestine that he practically went into hyperventilation when two Jews met their death! Or is that just a typical rabbinical reaction, based on the belief that one Jewish life is worth a million Arabs. Think of the irony, though—that the British were executing Jews who were fighting against them in guerrilla uprisings, just as the Germans had done to Jews fighting as illegal guerrillas against their soldiers. I wonder if the wise Shushani could explain to me the difference?

Now, Wiesel wades in even deeper:

How and why did Francois suddenly decide to join the struggle for an independent Jewish state? Had he, too knocked on the Jewish Agency’s door on the Avenue de Wagram? Though he joined the Lehi, and I belonged to the Irgun, our friendship was unaffected. In any case, each of us kept his activities to himself. We both agreed that the less we knew about each other, the better.6 No one asked questions at the synagogue I attended on the Rue Pave`e. To them I was a student like any other. If only they knew. [p165]

Wiesel is concious of a separation between himself and ordinary people, even other Jews who would naturally be aware and following what was happening in Palestine with great interest and concern. He has gone much farther, and is actually working for those in the “lower depths” of the bloody struggle taking place. Another strange phrase is “I belonged to the Irgun.” In his signature manner, Wiesel covers up his true identity and objectives, but reveals them in the words that pop out unawares. I have commented about the psychological aspects of this trait among criminals elsewhere. So many luminaries of the “resistance” funneled through his office every day that he, by any measure, has to be considered something of an insider within the Irgun.

Above: Henry Bulawko, according to Wiesel one of his fellow camp survivors and an Irgun associate.

Haganah soldiers pose in 1948.

Through work I met Shlomo Friedrich, the leader of Betar, Jabotinsky’s Youth Movement. He was a tall, vigorous man with a rapid gait, a former prisoner in the Gulag.7 […] The process of becoming a journalist involved attending press conferences, public meetings, and demonstrations, and offered a chance to meet such “colleagues” as Henri Bulawko.8 As we talked, we discovered that we had been in Auschwitz-Buna at the same time. And I met Leon Leneman, one of the first to sound the alarm for Soviet Jews. […] Envoys from the Irgun came to the editorial offices every day. All were from Palestine and I was supposed to know only their aliases. Their commander, Elie Farshtei, was shrouded in mystery, but, after swearing me to secrecy, Joseph told me of an incident from his past. In 1946 … he was captured and tortured by agents of the Haganah […] I was flattered when Elie Farshtei stopped by to ask whether I wasn’t working too hard, whether my studies weren’t suffering. I told him that everything was fine, and that I hoped he was pleased with my “contribution” to “Zion in Struggle.” […] In the corridors I might have encountered a young Jewish girl from Vienna, beautiful and daring, who transported documents and provided a hiding place for guns: my future wife.9. [p166-7]

Elie was in deep admiration for all these and many other fighters. No “Nazi” could be more in thrall to the leaders of his movement. He tried to ingratiate himself and win their approval. There is never a hint of concern or questioning about the damage inflicted on non-Jews, of the “human rights” of the native Arab inhabitants. He mentions only Jewish casualties. “A wave of terror swept over the Jewish communities in various Arab countries.” A synagogue was burned, “dozens of Jews were slaughtered in Aden, Jerusalem was besieged” and “gangs loyal to the grand mufti, the pro-Hitler Haj Amin el-Husseini (former ally and protégé of Himmler), attacked Jewish villages and convoys.”

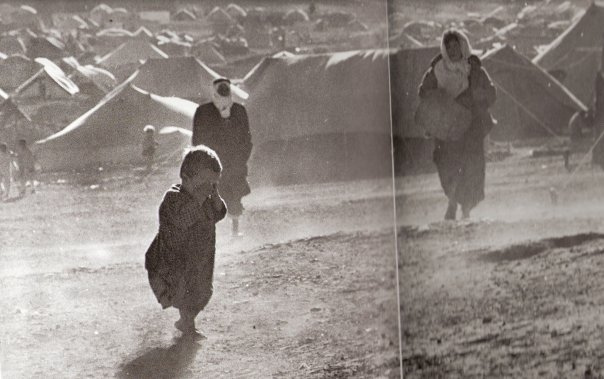

May 15, 1948: Beginning of a 62-year exile for 750,000 Palestinians

Tent city in Palestine, 1948

It would soon be May, and the day of independence. Mobilized units of the Haganah, the Palmach, the Irgun, and the Stern Gang united their efforts and their wills. It was imperative to protect every kibbutz, every settlement. The Zionist organizations in the Diaspora worked tirelessly to supply our brothers in Palestine with political and financial support. In France and in the United States as well, we were mobilized. Young and old, rich and not so rich, all felt the fever our ancestors had known in antiquity. Representatives of all the resistance groups worked day and night, though separately, procuring arms and ammunition, raising funds, recruiting volunteers who would set out for the various fronts of the nascent Jewish state. Elie [Farshtei] and his aides no longer found time to sleep. Out of solidarity, neither did we. [p167]

Excitement! All Jews, all over the world, were involved. Wiesel approved 100%, including the procuring of arms and ammunition. In spite of the fact that it was illegal, the “fever of our ancestors” justified it. You might be wondering why Wiesel didn’t speak in a more moderate tone when he wrote his memoir in the 1990’s; why he didn’t pretend a more universal concern for human rights in order to protect his reputation as a champion of human rights. I say he would not because he will never detract in any way from the utter righteousness of the installation of a Jewish state in Palestine. That can never be questioned, human rights be damned. That’s one reason Elie Wiesel is such a hypocrite. Other people’s struggles can be criticized and shown to be inimical to the rights of others, but never the Jew’s.

I find it interesting that Wiesel chooses the words “Young and old, rich and not so rich,” rather than “rich and poor.” There were no poor Jews? Or is it understood that this was a networking of those with means and influence; the poor were really of no help. They are just pawns in the game, used to parlay the idea that they are the ones for whom all this is being done.

My personal circle narrowed. Kalman left for America; Israel Adler was recalled by the Haganah and was now in a training camp …near Marseilles. My friend Nicholas informed me that he planned to abandon his studies [to go and fight.]

Deep down, I had reservations. Military life was not for me. […] what if I died in combat? I hadn’t yet done anything with my life, had written nothing of the visions and obsessions I bore within myself, hadn’t yet shared them with anyone. […] Nevertheless, I decided to heed the call to arms.

Nicholas and I signed up at the recruitment office … [p167-8]

Wiesel says he didn’t pass the medical examination. Really? Were they that particular? The doctor told him he was “not in good shape.” So he continued to work for the Irgun newspaper. Soon it was Friday, May 14, 1948, the day David Ben-Gurion read Israel’s Declaration of Independence over the radio. Wiesel claims to have been extremely moved, possibly beyond anything before in his life. “I was unable to contain my emotion. When had I last wept? It was in an almost painful state of reverence that I greeted Shabbat10.” [p169]

Left: David Ben-Gurion reads the declaration of “Israel’s” independence, May 14, 1948 in Tel Aviv. A portrait of Theodor Herzl hangs above him. Right: Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, in the same year.

* * *

The role of the Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe—collaboration with Poland, then Paris

At this point, I would like to insert some information about the role of the Irgun in Central and Eastern Europe from the website http://www.etzel.org.il/english/ac16.htm. It tells of the cooperation between the Polish government and Jewish “resistance” groups before the outbreak of WWII, revealing the desire of European nations, other than Germany, to reduce their Jewish population.

More than three million Jews, concentrated mainly in the large towns, lived in Poland in the 1930s. In Warsaw, for example, Jews constituted one-third of the population. The Polish government, worried by the increase in Jewish influence in the country, not only did nothing to hinder the illegal immigration movement which the Revisionists (Zionist faction of Jabotinsky – Irgun) organized in Poland, but actively assisted it.

In 1936, Jabotinsky met with the Foreign Minister, Josef Beck, and created the infrastructure for collaboration. The Polish government hoped that the establishment of a Jewish state would lead to mass emigration of Jews, thus solving the Jewish problem in Poland.

In 1937, Avraham Stern (Yair), then secretary of the Irgun General Headquarters, arrived in the Polish capital armed with a letter of recommendation from Jabotinsky. He met with senior government officials and laid the practical foundations for cooperation between the Polish army and the Irgun Zvai Le’umi. […] Polish army representatives handed over to Irgun members weapons and ammunition which […] were despatched to Eretz Israel. Some of the weapons were concealed in the false bottoms of crates in which the furniture of prospective immigrants was transported, or in the drums of electrical machines. When the consignments reached Eretz Israel, they were taken to a safe place, and the weapons were removed from their hiding place.

Stern was much helped by Dr. Henryk Strasman, a well known lawyer and an officer in the Polish Reserve force. The Strasmans introduced Stern to the Polish intellectuals and high officials. It was in their home that the preparations for the publication of the Polish periodical “Jerozolima Wyzwolona” (Free Jerusalem) were begun. His wife, Alicia (Lilka) designed the cover – A map of Eretz Israel with the background of an arm holding a gun and the words in Hebrew: ” ” (This Way Only). This became later the symbol of the Irgun. [See poster at top of page]

In March 1939, senior Irgun commanders from Eretz Israel participated in a course held in the Carpathian Mountains, instructed by Polish army officers. The course took place under conditions of great secrecy, and the instructors wore civilian clothing. The participants were not permitted to establish contact with local Jews, and the letters they wrote home were sent to Switzerland, inserted into new envelopes, re-addressed to France, and finally posted from there to Palestine. The trainees received military training and were taught tactics of guerilla warfare.

Three remained in Poland: Yaakov Meridor, who was responsible for despatching the weapons received from the Polish army; Shlomo Ben Shlomo, who organized a commanders course for selected members of Irgun cells in Poland, and Zvi Meltzer, who organized a similar course in Lithuania.

September 1, 1939 cut short the extensive activity of the Irgun in Poland and Lithuania. Most of the arms which the Irgun had received were returned to the Polish army and Irgun activity ceased.

After the war, the Irgun General Headquarters decided to renew activity in Europe and to launch a “second front”. The first base was established in Italy, […] As a result of arrests in Italy, Irgun Headquarters in Europe were transferred to Paris. Meanwhile, branches had been set up in various parts of Europe, and attempts were made to strike at British targets. A train transporting British troops was sabotaged, and an explosion occurred in the hotel in Vienna which housed the offices of the British occupation force. However, the blowing up of the British embassy in Rome remained the pinnacle of Irgun operational activity in Europe.

In January 1947, Eliyahu Lankin reached Paris after his successful escape from internment in Africa. Lankin was a member of the Irgun General Headquarters before his arrest and had also served as commander of the Jerusalem district. The French government, which knew of his escape from British custody, gave him an entry visa, and when he reached Paris he was appointed Commander of the Irgun in Europe.

Shmuel Ariel, sent to Paris by the Irgun in early 1946, was in charge of immigration. Ariel established good contacts with the French authorities, and the Haganah called on his services extensively in connection with sailings from France. Thus, for example, Ariel succeeded in negotiating with the French Ministry of Interior the granting of 3,000 entry visas to Jewish refugees arriving in France en route to Palestine. Some 650 of them left aboard the Ben Hecht, 940 on the arms vessel Altalena, and the remainder were transferred to a ship organized by the Haganah. Thanks to Ariel’s close contacts with the French authorities, the Irgun General Headquarters was permitted to operate in Paris without interruption, and to supervise activity in the many branches all over Europe.

While we hear so much about the “Transfer Agreement” and the Zionist collaboration with the German National Socialists under Adolf Hitler, where do we hear that beginning in 1936 the Polish Government was also desirous of, and actively engaged in, transferring their Jews to Palestine? As with the Germans, the breakout of war brought an end to this cooperation. But as soon as the war was over, it started up again in Paris. Paris was then the headquarters of the Irgun in Europe, with the approval of the French Interior Ministry. An Irgun special representative was in charge of illegal immigration to Palestine. Can this explain why Wiesel remained in Paris until 1955? It does shed light on the alternate world of underground Zionist operations that Elie Wiesel was absorbed into … just how deeply we can only speculate.

Next: Part III – Elie Wiesel’s travels and how they were funded.

Endnotes:

5. Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, p162

6. There is that “I didn’t dare ask” again; better not to know. You’re going to see as we go along that there are several phrases and numbers that Wiesel uses again and again.

7. In the Soviet Union, obviously.

8. A Lithuanian/Russian Jew born to an Orthodox rabbi, and a member of the French Resistance who was arrested in 1942

9. Wiesel is referring to Marion, whom he met and married later. As a “resistance” volunteer herself, she could well have delivered secret documents to his office.

10. Shabbat is the Jewish Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Category

Holo Frauds and Quacks- Printer-friendly version

- 14187 reads