In this section of his book, Giesler gives his impressions and an architectural critique on Albert Speer's June 1971 interview in Playboy magazine. I have included it in its entirety, even the more technical parts that were, in a few places, difficult for me to decipher from the part of Wilhelm Kriessmann's original translation which never went through the editing process between the two of us before he died in December 2012. ~Carolyn Yeager

Speer in the "Playboy"

From Hermann Giesler’s memoir Ein Anderer Hitler

Speer im "Playboy", pages 318-329

1977 edition, Druffel-Verlag

Translated byWilhelm Kriessmann and Carolyn Yeager

copyright Carolyn Yeager 2014

In the Summer 1971 my son brought me from America a peculiar magazine: Playboy, June 1971, the great interview “Albert Speer—Hitler’s closest confidant and second in command.”1 That interview in the sensationally edited magazine is accompanied by ill-reputed and illustrated jokes and by naked, boasting 'girls'. The answers given by the great ethicist and titan of repentance to the smartly questioning reporter, Eric Norden, in the multimillion-read magazine, are unique and way-out, and contain such wicked passages that they become unbelievable even at dimensions preferred by Speer.

The question arises : Did Speer really say that? As it seems, yes, because he did not distance himself from that Playboy-Norden interview.2

To my knowledge that interview has not yet been published in Germany. That’s why I will deal with some of the serious sections so I can point out the position of the converted Speer and his partly cynical tendency.

At first the magazine explains why they did the interview:

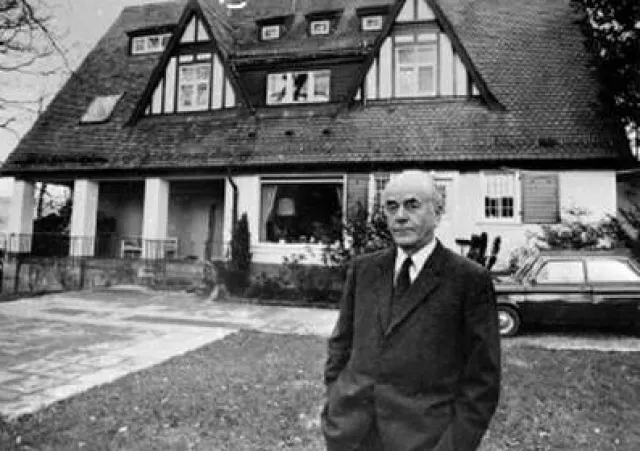

In order to find out the beginning and the scope of the Speer-legend and to investigate Speer's complications, his inner contradictions and character, the Playboy sent Eric Norden to interview the 66 year old ex-minister at his friendly wood house upon the hill, 3 miles from the university city of Heidelberg.

Norden writes:

Speer greeted me friendly and took me into the well furnished living room of his spacious house.

He still looks impressively like a distinguished manager. His bushy black eyebrows remind me of a younger man I saw in photos as he walked with his friend and patron Adolf Hitler through occupied Paris.

When we sat at the crackling fireplace sipping scotch and soda, snow began lightly falling outside and his 3-year old Saint Bernard, Bello, snored happily at the feet of his housemistress, who served us home made cookies and nourishing German tarts from heaped plates.

The atmosphere was so relaxed and gemuetlich that I forgot for a moment I was speaking to the man who, during world war II, stood beside Hitler in the second place of the Third Reich, the man whose organizing talents and energies contributed immensely to the death and suffering of millions. He appeared to me like some German of the upper middle-class, happy to have escaped his working office and now enjoying playing the role of a country squire.

For six weeks I studied that man, brooded over his book, the published interviews, as well as the numerous reviews and polemic articles by the American and European press. But when I bent over to turn on the recording set, I did not feel myself closer to the real man behind the well-known façade than before. During my research work about Speer I became frustrated by a certain non-existant transparency. And when we began talking I had the same doubts I faced during the time I read his book, and studied his public explanations. As sincere as he appeared to me on the surface, it seemed to me as if a veil was drawn between him and the truth.

I guessed, as also some of the reviewers did, that the litany of his self-accusations reflected an evading of final responsibility. Now, when I began the interview which stretched over nearly 10 days, with relentless question and answer sessions and which ended taking Speer as well as I to the edge of exhaustion, all that uncertainty remained, enforced by his strange attitude of indifference.

When my questions were asked till deep into the night and continued next day at breakfast, I recognized what bothered me most was his quietness, the way he accused himself of the most terrible crimes and with the same level voice offered me a piece of apple pie.

But when I listened to Speer describing terror and triumph of the Third Reich in German and fluent English. which he learned in Spandau, when I noticed during our tiring meetings how he tried with patient interest to tell and explain his doing at that time--I recognized this interview and all his other confrontations with the press and the public expresses part of the burden he is carrying, part of his repentance, stations on the road to his redemption he considered cannot be accomplished.”

Then the interviewer begins with questions. They offer Speer the opportunity to spread out for millions of new American readers his doubtful mea culpa, his dramatic repentant confession, his distortions and, as Norden writes, “the litany of his self accusations.”

This is not my cup of tea. I am interested in questions and answers I can judge, about Adolf Hitler's city-building and architectural planning, the discussion of Norden-Speer about the renewal of Berlin. My sons translated for me and were reading :

“All that moved me in those days,” Speer said, “was my ambition to excel as Hitler's architect.”

Your ambition seemed to grow in proportion to the crimes committed by your benefactors, Norden suggested.

“Yes I assume so,” Speer answered and continued, “I think Hitler planned from the beginning on to engage me with a task he was dreaming to fulfill since his youth.”

Now Norden asked him when Hitler first talked to him about those plans.

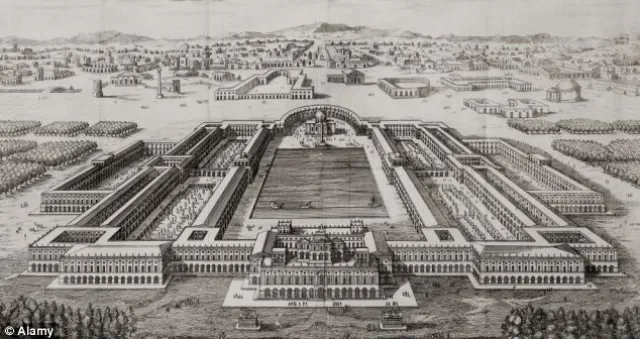

“He called me in September 1936 and unexpectedly gave me the biggest job of my career: together we would rebuild Berlin as the dignified capital of the Third Reich. The plans for his new Berlin were indeed astounding and its execution, I was sure, could turn me into one of the famous architects of history. Hitler imaged a gigantic new capital renamed Germania, at the same time seat of his Reich and the monument to keep the memory about him forever alive. The city's core would be flattened and be replaced by a 3-mile long boulevard called the “Prachtstrasse” (Splendor street).”

I interrupted and said:

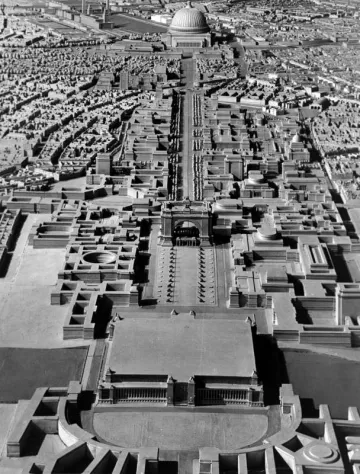

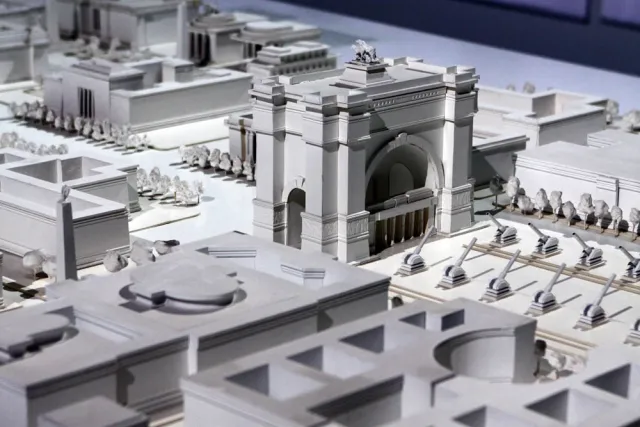

Speer’s description is completely distorted and also factually incorrect. Look at the photo of the over-all model of the Berlin renovation. Speer published it in his Erinnerungen (Memoirs), wavering between pride and played sarcasm. Look and understand what Hitler aimed at. No way a new gigantic Reichscapital, but rather to introduce new building ideas and give Berlin's shapeless center a new image and order. He picks up a architectural idea of the early 19th century: Schinkel planned at that time to complement the only representative East-West street system, the Great Kurfuerst's “Unter den Linden” with a North-South opening, to offer an expansion to the capital.

It is not like Speer said, that the heart of the city would have been leveled. The open space for that urban renewal would have been gained primarily by eliminating the large railway system … Read further ahead and you will recognize this tendency of Speer's.

Hold on, I interrupted, that’s not correct, but maybe the interviewer Norden caused some confusion. Not from the Brandenburger Gate should the “splendid avenue” stretch itself out, but from the planned South station towards the North to the square in front of the Reichstag. It was passing by the Brandenburg Gate at its West side. As a large traffic axis it should begin at the Autobahn circle, cross the East-West axis and connect with the Autobahn circle at the North.

And the comparison with the Champs Elysee is purely arbitrary. Already today the connecting Avenue Foch, conceived during the regimes of horse carriages, was twice as wide as the Champs Elysee.

My sons translated further:

Well, well, I said, if he figures four persons per square meter without reductions for entrance he might just come out right. I know his Cupola and its dimensions. But continue with the story:

Objection. Speer was certainly misunderstood here; Playboy mistook the locale. That giant stadium was supposed to be built at Nuremberg, or did Speer build it once more in Berlin? The size scale originated with Speer, who brags to have surpassed Adolf Hitler's scales, which he now calls megalomania. Yet, the Roman circus maximus at the foot of the Palatin had, according to Gregorious, a capacity of 385,000 people. Lets continue:

Nonsense, those were two different building-groups.

“new headquarters for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Party, the Luftwaffe and a new parliament building for his Yea-saying Reichstag ..”

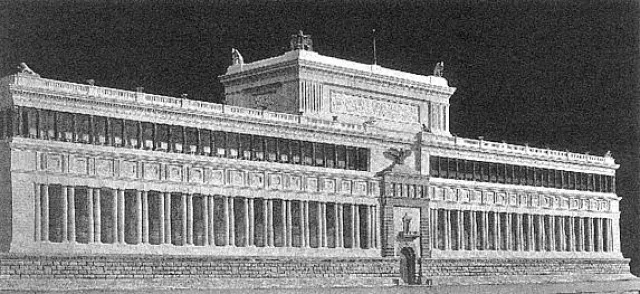

What a confusing description—and yet Speer forgot the building for Goering with the column salad, the Reichsmarschall's staircase-house. Here, look at it!

I pointed to the photo of the model of that staircase house in Speer's Erinnerungen. I can still hear Adolf Hitler's voice when he said the Reichstag building should be preserved. It's there in the overall model, clearly visible.

Speer then described the projected “mighty (Cyclopean)) fortified “Fuehrerpalace.” I asked for a repeat reading, it sounded so unbelievable.

There is no doubt about the untruth of the measurements of that area; also no mistake of converting the square foot to square meter as I originally thought because Speer topped that strange statement by the following comparison:

No, I said to my sons, this is not an error or a mis-hearing by the Playboy interviewer Norden, but a silly, manipulating description by Speer. He presents here a whopping untruth which a blind man can touch with his cane—which I would say any architect can measure with his measuring stick. With such nonsense, Speer apparently wanted to demonstrate to the unwary American reader a despicable Hitler.

I took a ruler and we started to calculate. According to Speer's own planning I arrived at 22,000,000 square feet—approximately 2 million square meters—still 254,600 square meter are a rather big footage for the whole building area. And the actual area would have amounted to 106,000 square meters, including the “dining room for several thousand people” and also the office tracts for the Reichs-Presidential-and-Fuehrer offices. It really is the reverse of Speer's description.

Beside Nero's Golden House, the “Fuehrer Palace Complex” would have “shrunk to the insignificance” of about a quarter of Nero's scale even by Speer's own megalomania. Such surface area confusion and measurement distortions by Speer can be clarified by a look at the respective literature:

“Nero's 'Golden House' had 1 kilometer at its square (one million square meter, 11 million square ft). A single lake of that vast area could later become the construction ground for the Colosseum. The audience hall of the Flavian state palace at the Palatin was quite wider than St. Peter's cathedral. Inside the Tepidarium of the Diocletian thermal springs, Michelangelo could build the splendid church of St. Mary degli Angeli—ruined later on by Vanvitelli—and the giant roundel of Rome's railway station is nothing else but the exedra of the same thermal springs. Similar comparison can be seen between the piazza Navona and Domitian's Circus Agonalis. By its challenging high spirits (Uebermut), yes, by the hubris of its dimensions and the natural perfection of its creation it announces a true elation for what men can do on their own and, by its hardy optimism, in spite of its late creation, still very much with the heart of the antique paganism." (A quotation of Fritz Alexander Kauffmann, Rome's eternal face, Murnau 1940)

I added to it: When I looked at the gigantic Roman structures, may they be the Coloseum, the thermal springs, Konstantin's basilica or Hadrian's sepulcher, it never occurred to me that they express a hubris in their dimensions. I recognized them as the extent of the Roman power of expression. And if you interpret that hubris as a “sinful high spirit” then I myself will convincingly and frankly agree with it.

The reformed (changed) Speer, I continued, does not, however, admit it as he now explains. He does not have the heart to feel the high spirit of that 'paganism.' Otherwise he would today not cloud the harmony which we could have experienced with scorn and derision. And I again hear Adolf Hitler’s voice when he said: 'Not for me, I do not need that—for my successor.' In the size and at the same time in the limit, which I think is right. And that limit can be seen in the over-all view of the model which does not correspond with Speer's design on the following page of his Erinnerungen. His description in the interview and in his memoir does not comply with the model.

We continued reading the Playboy :

“Hitler believed that after centuries had past, his gigantic assembly hall would obtain a great venerable significance, and become a holy shrine for National-Socialism like St. Peter's Cathedral was for Roman Catholicism. Such a cult was the basis of the whole plan. He imagined his new capital as an eternal alter of his greatness, to immortalize his political credo (Weltanschaung). By using stone he was planning to make sure to gain immortality like the old pharaohs. Germania would become a sarcophagus and not a city.”

And again I had to interrupt the epic flow of the interview, not because of Speer, but to point again to the pictured model of the Berlin design: What a sovereign and convincing creation of city building based on Adolf Hitler's ideas! The arrangement of the North-South axis is unique. All proportions and scales of the square and street spaces, and the buildings themselves, judged by city building standards could not have been better. The intervals between the vertical and horizontal buildings are tightened and full of tension, the crowning finish is the all dominating cupola hall giving the central space that which had been aspired to for centuries.

The possible critique on details is of secondary importance compared to the magnificent overall concept that does justice to the multi-million-occupant city without reaching, let alone exceeding, scales set up by the Great Kurfuerst already built in the 17th century for the ten (and later forty) thousand-inhabited city. The 60-meter-wide avenue “Unter Den Linden,” its development and the large-dimensioned castle by Schlueter, were, by the same standards, “megalomaniac” compared to the small-scaled village-type buildings of the time.

This fascinating city renewal task was given by Adolf Hitler and it was up to the responsible architects if and how they handled that order—if they would do justice to that task. Contrary to his ideas at that time, Speer sees it now that, by his effort, Germania would not have become a city but a sarcophagus!

I don't agree with that either and I repeat: The superior idea of building a traffic-friendly city renewal dominates; the rhythmical order of the masses of buildings convinces and is permanent. If some details give reason for criticism, it could not destroy the overall concept of a city renewal. It is strange that I, his “opposite-player in Munich,” am called on to protect Speer's earlier assumptions of Adolf Hitler's rebuilding plans against the current “Mr. Reeps.”

That the Führer Palace should outdo Nero's famous “Golden House” by two times corresponds with Speer's gigantism and not with Adolf Hitler's demand. Adolf Hitler's needs for housing and representation were well-known to me because he wanted me to design his private home, first in Munich and then in Linz. His personal requirements were moderate, even modest. They were, however, different when he had representative buildings for the nation in mind, among them also the Führer-palace because “my successors will need it.”

Giesler recalls Hitler in Paris

And then follows again a cut back: At the nightly talks with me at the various headquarters until 1945 he always pointed out the necessity to check very carefully many of the building plans in order to arrive at a clear gesticulation (Gebaerde) of the architecture. He insisted on a modern tectonic justifying the use of steel and steel-concrete. Severe simplicity should be striven for to comply, with dignity, to the sacrifices of the war. Those thoughtful demands of Adolf Hitler corresponded with my own principles in my work as his architect.

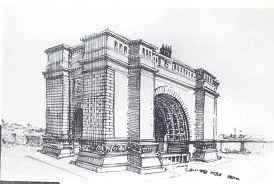

The triumphal arch and the cupola hall were based on Adolf Hitler's design sketches and scale notes from 1925. He talked to me several times about the size relations of those buildings, as in Winniza remembering the ride thru Paris at the end of June 1940, impressed then by the Champs Elysees, the Etoile and the Arc de Triomphe.

At that time, Adolf Hitler recapitulated:

"Thru the haze of an early summer morning we drove from the large Place de la Concorde along the Champs de Elysees. The view towards the Arc de Triomphe was uniformly integrated by the greened tree rows of the street, but even by that street-space-limiting way the Triumphal Arch (at right) seemed to be too small. Certainly so when in winter the leafless trees opened the view all the way up to the buildings along the street. The Etoile is for our present motorized epoch too small to be useful as the final traffic square for dispersing 12 boulevards and streets; it will be split up and displaced. But then again the Etoile could not be made larger by adding the tree growing gardens of the neighborhood, for the harmonious scale of the Arc de Triomphe will be affected.

"In Berlin, the Triumphal Arch will arch across a street cross, its dimensions and cubic masses will concur with the proportions of the square and wide street spaces. Yet I see the Great Arch always as the primary manifestation of our idea to build a monument for the soldiers who gave their life fighting for Germany, and the symbol for all the struggles for our nation and her existence. Feeling this way, I sketched this arch at that time [in 1925, at right] with the Gloria (glorification Sieges/Ruhm Goettin) inside, under the high, massive, heavy domed ceiling. That Gloria fulfilled a dual purpose: as contrast to the mass as well as disclosing the scale."

The cupola hall [the Great Hall] with her diameter of 250 meters expresses the powerful strength of the Party, but also a proof of what 20th century technology can do.

For a superintendent [a Protestant clerical title], it would naturally be too large. The idea what kind of a church by which the Protestant religion should be represented is demonstrated by the numbered seats at the Berlin cathedral. [A cynical comment referring to the poverty of spirit of the Protestants. -cy]

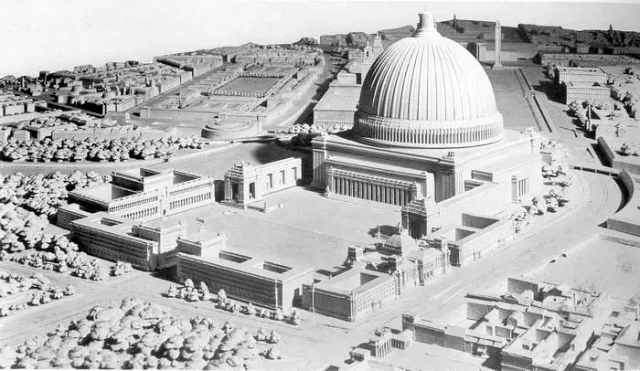

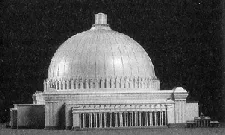

When Speer was working on the detailing of the model for the triumphal Great Arch (he presented it to Hitler on his 50th birthday,1939), he kept to the sketches by Adolf Hitler of 1925. [see at right] But as I explained, he departed completely from Hitler's original drawing when working on the plans for the “Great Hall,” the cupola hall, including on the model, which was very detrimental to the whole idea of that structure.

Hitler's drawing

What I explained to my sons can be easily checked. Hitler's drawing of the gigantic hall reflects calmness and dignity. The quadratic, monolithic colossus is basically drawn along the scales of the Golden Mean (Goldene Schnitt) and carries the flat cupola effortlessly.

The generously graded tambour/drum rises clearly out of the stone colossus and lets the cupola float. Even on the sketches you can feel by the shape of the cupola and the wingspan of the ribs, the material: steel. That gives the giant the scales and technology of the 20th century.

Even the portico of the entrance hall does not disturb the unity of the edifice by its over dimension of the scales of the classical order. That portico certainly reflects a reminiscence of the entrance hall of the Roman Pantheon.

The structure of “The Great Hall” is very familiar; one thinks about Gilly and Schinkel. It might well be a giant, but not a stranger in Berlin.

Speer's design

It's different with Speer. The stone-cube is flattened and has to be supported by pillar-towers. The broadly set dissolve of the wall area by the entrance hall seems to weaken the foundation. The tambour moves away quite a bit from the supporting stone structure, an addition of the cupola whose parabolic ascending curve denies the steel construction: the cupola does not float anymore, it weighs. Eighteen segments of the cupola appear before your eyes—by that tight setup they turn into scaled segments of a stone vault wrapped into metal, a giant forest of green patinated copper. If you take an overall view, then only nine out of the numerous segments would conform with the technological-static spans of a steel construction, as it was suppose to be done.

The tambour—Michelangelo's vivid one at St. Peter's or the calm one at the Florentine cathedral—swings away from the cupola. That tambour degenerates in Speer's model to a powerless affectedness.

Speer took away the giant's uniqueness and dignity by petty scales. Etienne Boullee of the 18th century, Friedrich Gilly or Friedrich Schinkel of the 19th, would have mastered the idea of structures with the technology of our time.

Back to the Playboy interview. To the question: Do you have any lingering regret that those plans have never been completed, Speer answered:

“I have to admit that regardless of its absurdity and madness I still find it difficult to free myself completely from the power those plans had on me for so many years. Understandingly, I can now despise them; but deeper inside myself they still have a hold on me. Maybe that is one reason, beside others, that I hate Hitler so deeply. He not only enabled me to destroy my conscience but consumed and perverted the creative energies of my youth.”

However, Speer is not yet at the end of his answer to the Playboy question. He further says:

“But because those plans still create an inner fascination for me, I am glad that they have never been completed. I can see now, what I could not see then, that they were, at their conception, immoral. The proportions were alien, inhuman, reflecting the frigidity and inhumanity of the Nazi system. 'I build for eternity,' Hitler used to say to me, and that was true. But he never built for people The size and scales of his monuments were a prophetic symbol of his idea of ruling the world. And the gigantic metropolis he imagined could only serve as the heart of a conquered and enslaved empire. One day in summer 1939, when we stood in front of the wooden models and Hitler pointed to the gold German eagle with the swastika in his claws, a crown at the top of the cupola hall: 'That has to be changed,' he said with emphasis. According to his orders, I changed the design so that the eagle was now holding a globe in his claws. Two month later World War II broke out.”

I interrupted the translation once more: “That Adolf Hitler had a Germanic Empire within a United Europe in mind, one can not deny, nor condemn. Without doubt Germany, or the planned Germanic Empire, would have been a world power. But that Adolf Hitler planned to rule the world, or a world empire, that is not only nonsense, it is a misinterpretation, a speer-lish rubbish.”

When Speer mentioned that the eagle at the top of the “Great Hall” signified world rulership, that is as if the provincial president in Duesseldorf claims world rulership because his office is crowned by an eagle who holds a globe in his claws. Especially suspicious and dangerous is the fact that recently the eagle and the globe were again put on the building and gold-plated. That the lantern of the Berlin cupola ends at a globe with an eagle spreading his wings is a sculpture, commonly used. It had to end that way—very evident for any architect, not however for Speer.

In order to characterize Speer's tendentious efforts, I opened one of the pages of his book Erinnerungen showing a photo of the model of the “Great Hall.” The gigantic cupola hovers like a gruesome nightmare over the Brandenburg Gate and the Reichs Parliament building. [Photo above] Terrifyingly, it takes your breath away until you orient yourself by the following page of the book and recognize how far apart and by what spaces in between the individual building groups are from the “Great Hall.” The model photos on the two pages of the book shows everything as piled into each other and above each other. “How strange those perspectives shift” Speer writes on another occasion, but it fits with the above.

The deficiency of photo technology offers itself for such picturesque distortions—no wonder that the Zugspitze [Germanys highest mountain] was also adopted to that panopticon in order to shrink when compared to the size of the parabolic cupola!

Speer zealously condemns his planning of Berlin and means that everything was not only crazy, but also boring, lifeless and regulated. But where his own gigantism breaks through—in none of his statements can he hide that—he turns it into Hitler-megalomania whose influence he could not escape, regardless of its absurdity. What Speer has to offer is a macabre mix of personal disappointment and a “know better” arrogance, ending with a self portrait where he again and again points out his mea culpa of a moral integrity.

The question arises—what kind of a split personality appears here, putting himself on a pedestal of an ethical principle and then vulgarly triumphing to say: Finally I could pay him back. Yes, he wants to defame Adolf Hitler. But he does not describe the man, he moves in the shadow that man casts.

Two significant responses I quote from the Playboy interview:

Question : Were there many inside fights in Hitler's entourage?

“Hitler's circle was like a Byzantine court, seeding with intrigues, jealousy and betrayal. The Third Reich was less a monolithic state than a net of opposing bureaucracies fighting each other and Hitler's satraps stacking their own, independent spheres of interest, expanding it scrupulously—often damaging the national interest.”

Quite a bit of that refers to Speer himself, he was masterly in his ablity to stack and expand his spheres of interest!

Question: Were Hitler's courtiers as corrupt as they were ambitious?

“Most of them would have let your American chap Al Capone look like a philanthropist.

From the moment they took over the power and had their hands on the state's treasury, they filled their own pockets, piled personal riches, profited from government business, built large palaces and country villas with public money, allowed themselves an extravagant lifestyle more fitting the Borgias than so-called revolutionaries. Rot penetrated everything; like a fish the Nazi government rotted from the head down.”

When that was translated for me I had enough and thought: The decent things at that Playboy magazine are the ill-reputed jokes and the naked girls. I looked at my sons who watched me during the reading and the lecturing, partly amused, partly worried. I leafed back to the first page of the interview and pointed to the three photos of Speer used as a subliminal subtitle for the introduction—the facial expressions selected to correspond with his statements—and I said, “Look, what a man! No, what a Saeulenheiliger!”3

Endnotes:

1. How many of Hiter's associates have been called his "second in command:" Rudolf Hess, Martin Bormann, Heinrich Himmler, and now Albert Speer. In truth, none of them were.

2. Speer told David Irving that he was misquoted. He claimed that Playboy magazine had grossly distorted the interview with him. He was not shown the English text before it was published, and the interview was conducted in German as his own English was not up to that standard. Irving wrote:

We discussed initially the book by Professor Hermann Giesler, Ein Anderer Hitler. Speer was negative about it. The book contained two completely wrong statements about him. There is, he says, an entire chapter attacking him. One wrong allegation is the suggestion that the BBC flew him to London under a false name, Reeps. The other point I cannot remember. However he agrees that Giesler's descriptions of the Landsberger Haftzeit (Landsberg prison time) and other Hitler matters may possibly be correct. I laughed at the way that the rival architects versteiften sich in solchen Kleinigkeiten (stiffen over such trifles).

But Speer is also quoted as saying that he is in basic agreement with everything in the interview.

3. A stylite, or pillar-saint is a type of Christian ascetic in the early days of the Byzantine Empire who lived on pillars preaching, fasting and praying.

- Printer-friendly version

- 23068 views