The following is something of a masterpiece of satiric wit from Giesler. -cy

The Column Saint

From Hermann Giesler’s memoir Ein Anderer Hitler

Der Säulenheilige, pages 355-360

1977 edition, Druffel-Verlag

Translated by Wilhelm Kriessmann and Carolyn Yeager

copyright Carolyn Yeager 2014

In the year 113 the Roman senate erected a gigantic column for the emperor and military leader Trajan. (Shown right) On the capital of the column stood the gilded statue of the honored.

The art historian Bruhns writes ”Used to gigantism and always striving to exceed, Rome created that form of eternal triumph which then did mankind not less convince of its greater impression than the older kind of triumphal arch, now of a lesser rank. As the colossal column expresses the idea of “height” exceptionally well, it can also be used very well for the adoration of the “highest.” Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius were given similar columns in Rome. Arcadius got his at the new capital Constantinople.

When Europe during the Napoleon era felt itself specially close to Rome’s greatness, it presented the new emperor with the Vendome column in Paris—and his conqueror, Alexander of Russia, a second one in Petersburg.”

The emerging Christianity overthrew the images of antique greatness and now paid homage to its believers on imposing columns. After the final decline of the ancient dignities around the 4th and 5th centuries, ascetic Christians requested the top of the Roman columns as pleasing to God. The best known among them was Symion Stylites from Aleppo. Those ascetics and penitents, called stylites or “Säulenheilige (column saints), strove to increase their ranking by self-elevation.

To enhance oneself—who wanted to hinder the column saint, standing between earth and heaven? Was he not predestined, by his high location from where he could overlook everything, to judge the bad, and if it had to also be mentioned, the good? Everything that came down from isolated but triumphant height was important, even scolds and abuses, if quite a bit drew attention only post festum (too late).

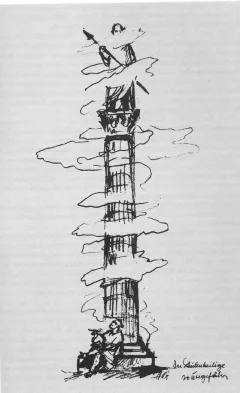

In Speer's Spandauer Tagebuecher I saw some caricatures sketched by his colleague Hans Stephan [on p494]. They were done during the high time of planning Berlin's renewal. Speer commented: “We treated our own gigantism ironically.”

Now I remembered Stephan's ironic caricature. [Shown at right from page 357 of Ein Anderer Hitler] At first it seemed to have a double meaning but looking closer it was pretty obvious: One giant column pushes through layers of myrrh and incense, or even through clouds, up to an extreme height. Sacrificial smoke also shrouds the statue, clad in a Roman toga and holding a spear, characterizing the “most enhanced.”

At first one would consider it as an antique Caesarean honor. But on the three step base of the column sits the chronicler dressed in a capuchin robe, busy and carefully making notes about all thoughts of the “most-enhanced,” of all his confessions and opinions but also his scolds, to make it known to the interested present and future generations.

The caricature referred to that time, but with the monk on the bottom of the column it was, as it has turned out, also pointed to the future. Stephan had portrayed as well the imperatorial present, as he pointed with a fine vision to “what is to come.” The monk on the column base does not allow any other interpretation. Did it ever dawn on Stephan how significant his depiction would become: Speer as a column Saint?

Yet, after all, he put him a few column-drums higher than the ascetic and scolder Symion Stylites from Aleppo. Because, as an architect, Stephan had a good feeling for rank and file.

After the publication of Speer's books I met quite a few who thought his strange change, his schizophrenic fantasies, his distortions and his obsession for abuse—plus his awkward readiness for remorse—were the result of 20 years of “jail-torture by isolation” as they used to call it, according to Sartre. I opposed that. There was too much influence from the world around him. It might be that the imprisonment aggravated the contours. Speer's “turnaround” is mere opportunism, cold and carefully planned, as it is in conformity with his genetically generated character—demonstrated already before his jail time.

Nuremberg, Prison and Beyond

After the grotesque comedy of the Nuremberg trials, when Speer tried to tie the bear Tabun (nerve gas but also the name of a Teddy bear -wlk) to the court-benches: “I had the intention to kill Hitler by poisonous gas however...” He was addressed by Kranzbuehler, the attorney of Grossadmiral Doenitz, who asked Speer if it would not have been more certain and more effective to shoot Hitler than start a poison gas operation endangering an unknown number of secretaries, drivers and others, without being sure to even get Hitler himself. Speer answered: “I could not shoot.”

The attorney's remark since: “That was enough for me to characterise his personality, and both his books only convinced me more.”

The experiences and statements of this former fleet lawyer need a further explanation: Had he known Stephan’s caricature, he would have reached another opinion, for from a column saint you do not expect that he knows how to shoot! Poison, however, you could imagine with a stylite. But again, not with Speer, the “second most important in the Reich”—he was only short of a ladder to execute the planned deed at the air shaft of the command bunker at the federal chancellery.1

In the “innermost circle” of the Speer boys they might have whispered about passionate plans while completely ignoring the real situation. Only in that way can I explain the phone-call of his colleague to the “central planning department” from cage to cage, in the prison winter of 1946: Nothing will happen to Speer—he will be the German minister for reconstruction! His willing guilty confession, combined with his assassination-attempt-declaration, would no doubt form Speer's basic defense. But it was only the first propaganda-cry of the first re-educator sent by the Americans to the German people. It became a success also of the crook “Dr.Gaston Oulman.”2

Beginning with the desperate Charivari 3 of his statements at the military tribunal, Speer intensified, as a prisoner, his unscrupulous abuses by quotations and secret messages, and then, after 20 years, as a free man in his books and interviews, not sparing even the victims of the victors' justice.

In order to justify himself in facing his children, so that they would not be ashamed of him, and “to help once more” the German people4 by, as he believed, his sincere attitude, he thought he had to take away from the fallen of the war, the fighters for the freedom of Europe, the meaning of the deep sense of their sacrifice. For the surviving dependents it must certainly be comforting to hear from Speer that their men—sons and brothers—were sacrificed, that their women and children were bombed, for a wrong ideal and for “a total madness.” Thus Speer has, as he wrote, “served his own people the best way.”5

There is also the infamy of the Nuremberg tribunal. Speer formed a bond with the American chief prosecutor Jackson. If there was ever a doubt about that, Speer arrogantly confirmed it 30 years later: “When Jackson started with his cross-examination, he smiled friendly. Anyway,” Speer continued, “I would have cooperated with anybody who would have supported my line to let the Germans regain common sense.”6

In his Erinnerungen, his Spandauer Tagebücher and in his scolding interviews, he tries to manipulate history and events. He wants to be involved in the confusion of the German people even though he thus exposes himself to the suspicion of a lack of historical awareness and truthfulness.

Horse dung [Rossapfel, Ross=horse] found on his bed in the Spandau jail put him into a schizophrenic frenzy. Speer associated it with the Reichsapfel, the imperial insignia of power and dignity. Then the horse dung is brought into a connection with the eagle holding in his talons the world globe.7

He discovers the “deeply criminal character” in Hitlers face and he believes he has to assume that a part of Adolf Hitler's success was based on an audacity to pretend to be a great man.8 But enough of all that.

Who does not remember? Speer was at that time considered to be the confidant; he appeared to be the Johannes very close to Hitler's heart. Naturally it was Speer's smartness, his extraordinary organizational talent, the nonchalant way he put himself into the scene, his ambition and effort to gain recognition and power—indeed he felt himself already as the sage. Therefore it was no surprise that Stephan placed him for adoration on top of the High Column, decorated with the leaves of the Acanthus. Towards the end, however, doubts entered and Christian soldiers carried out the fall of “the enhanced.” After his conviction, a cruel road lay ahead of him for decades. To alter his reputation, he severely re-shaped himself as is so fitting to his character.

With will power and toughness he began that road and walked on it. One can assume without doubt that he believes in himself and his strange mission. He reached his goal anew by his own way and under peculiar signs. Thus he remains on a high column, completely changed as Baal Teschuwa, the son of repentance, as his friend the rabbi Geis calls him.9

He wrote his Erinnerungen as that man, praised by the American historian, Professor Eugene Davidson as “an historical testimony par exellence” and as an “absolutely priceless document.” It took the writer Zuckmayer's breath away when he read the Spandauer Tagebuecher.

Speer begins his Erinnerungen with an aphorism of the theologian Karl Barth. Yet it would have been more fitting to begin with the caricature by Stephan—one would then be prepared for the confessions of a reformed person, the opinions of a column saint.

Notes:

- Speer testified at Nuremberg that his plan to kill Hitler by placing poison in an air vent into his private bunker failed only for lack of having a ladder high enough to reach the vent!

- A Vienna-born Jewish jailbird with the name Walter Ullmann, who called himself Dr. Oulma and became a radio commentator at the Nuremberg trials, before being unmasked and causing a big scandal.

- A ritual used by Europeans to chastise community members who did not conform with social expectations.

- Speer, Erinnerungen, p594

- Eberhard Wolfgang Möller, Albert Speer oder das achte Gebot; in: Klüter Blätter,21. 1970, p53

- Welt am Sonntag of Oct. 31, 1976

- Speer, Spandau Tagebücher, p247

- Ibid, p52

- Ein Mensch namens Albert Speer; Das Evangelische Darmstadt, Oct. 17, 1971

- Printer-friendly version

- 6605 views