by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2008 Carolyn Yeager

Hanna Reitsch is unusual in being a feminine woman who was yet the equal of men in a dangerous male profession – test-piloting new military aircraft. Her love of flying from childhood on, along with her superior intelligence, determination, and ability to withstand tremendous stresses, gave her the edge that allowed her to rise to the top of the aviation world.

Hanna Reitsch is unusual in being a feminine woman who was yet the equal of men in a dangerous male profession – test-piloting new military aircraft. Her love of flying from childhood on, along with her superior intelligence, determination, and ability to withstand tremendous stresses, gave her the edge that allowed her to rise to the top of the aviation world.

Hanna Reitsch offered her gifts to the German nation in the same way that Adolf Hitler and many others did – with a complete giving of herself and her abilities, holding nothing back. Although she lived to 1979, she never renounced her participation with the National Socialist government or criticized Hitler, even under pressure to do so. Hanna’s life story is an amazing one that sounds almost unbelievable in its drama and acts of heroism. She never married or had children; instead she occupied herself with the two burning loves of her life – flying and the salvation of her beloved Fatherland in its time of need.

Reitsch was born on March 29, 1912, in Hirschberg, Silesia. Always fascinated with flying, she reportedly attempted, at age four, to jump off the balcony of her home. In her 1955 autobiography The Sky My Kingdom, she wrote: "The longing grew in me, grew with every bird I saw go flying across the azure summer sky, with every cloud that sailed past me on the wind, till it turned to a deep, insistent homesickness, a yearning that went with me everywhere and could never be stilled."

At age 14, to assuage both her Protestant ophthalmologist father and her devout Catholic mother, she decided to become a flying missionary doctor in Africa. She came to an agreement with her father that she would be allowed to learn how to fly after she completed secondary school IF she did not mention it to him again during that time. To discipline her mind and develop highly focused concentration, she studied the writings of Ignatius of Loyola. Thanks to her determined silence, she managed to fulfill that pact and was allowed to go to the Grunau School of Gliding, with the condition that she also take a course in "domestic science."

Reitsch undertook these studies at the Colonial School for Women at Rendsburg. The course included how to care for domestic animals as well as to ride and shoot. While she could appreciate the value of what she was learning, her real goal remained flying. She was the only woman in gliding school, and was derided by both the male students and instructors. Authorities were so taken aback when she was the first class member to pass the “A” level beginning course that they made her retake the test -- which she once again passed. She went on to pass the "B" and "C" tests before beginning medical school at the University of Berlin.

Again she sought permission from her parents to continue with flying lessons. She later recalled, "I managed to convince them that for my career as a flying doctor in Africa it would be necessary for me to learn to pilot engined aircraft." Deciding that a pilot needed to understand how the engines of their planes worked just as a doctor needed to know about the heart, she started to hang out with the mechanics at the flight school. As they saw she was not averse to hard work or dirty hands, and was serious about learning about airplane engines, she worked herself in their favor.

The quality of Reitsch’s determination is revealed in the following incident:

One Friday the master mechanic pointed to a worn-out engine and told her that she could have it to take apart and put back together again by the following Monday. She did just that, later recalling, "on the Monday morning, with torn and bleeding hands and covered from head to foot in oil and grime, I was able to show the foreman the reassembled engine."

W hen Reitsch decided she needed to learn to drive an automobile, she solved the problem in the same creative and hard-working fashion - she did the dirty jobs for the workmen who were operating earthmoving machinery near the airstrip while asking them questions about clutches, brakes, chokes and carburetors. They finally let her drive some equipment.

hen Reitsch decided she needed to learn to drive an automobile, she solved the problem in the same creative and hard-working fashion - she did the dirty jobs for the workmen who were operating earthmoving machinery near the airstrip while asking them questions about clutches, brakes, chokes and carburetors. They finally let her drive some equipment.

The Test Pilot

In 1934 Reitsch traveled to Brazil and Argentina as part of a German research expedition to test-fly gliders in extreme thermal conditions. Because of her growing reputation as a pilot and the opportunities now presented to her, Reitsch left medical school and accepted an invitation to become an experimental glider test pilot at the Deutschesforschungsinstitut fur Segelflug (DFS), the German Research Institute for Sailplane Flight at Darmstadt, where she was involved in flight testing to address problems of stability and control, and structural vibration. She also test-flew the first glider seaplane and evaluated the capabilities of new glider catapult mechanisms.

In 1936 Reitsch met Ernst Udet, the highest-scoring German fighter ace to survive World War I, then a head man at the Ministry of Aviation. At the time, she was working on the development of dive brakes for gliders. After demonstrating the use of dive brakes in a vertical dive before Udet, other Luftwaffe generals and German aircraft designers, she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she was designated as a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot, a post she would hold until the end of World War II. Reitsch and Udet shared a passion for flying and developed a close professional relationship that lasted until Udet’s death in November 1941.

Another former fighter pilot who was impressed watching Reitsch’s high-speed dive brake tests was Robert Ritter von Greim, a Bavarian ace who had scored 25 WWI aerial victories, been awarded a knighthood and the coveted Orden Pour le Mérite. Greim was the first squadron leader of the new Luftwaffe, appointed by Reichsmarschall Göring.

In the years leading up to WWII, Reitsch made a name for herself by being one of the first Germans to fly a glider over the Alps, setting a world long-distance record in gliding, and winning the National Soaring Contest - the only woman entrant. She also traveled extensively, to Africa and to the United States. After completing her test pilot duties in the development of dive brakes, Udet appointed her a civilian test pilot at the primary Luftwaffe research station at Rechlin, where she was allowed to fly most of the high-performance aircraft in the Luftwaffe inventory. She viewed them as guarantors of peace, later writing: "Stukas - bombers - fighters! Guardians at the portals of Peace! And in this spirit I flew them, each time in the feeling that, through my own caution and thoroughness, the lives of those who flew after me would be protected and that, by their existence alone, they would contribute to the protection of the land that I saw beneath me as I flew....Was that not worth flying for?"

I n February 1938, Reitsch would become the first person to fly a helicopter inside a building, Berlin's Deutschlandhalle. She had previously been called on to demonstrate the Fa-61 to American aviation legend Charles Lindbergh at Bremen, whom she afterward described as a man "whose simplicity of manner won all hearts wherever he went." She also became the first woman to be awarded the Military Flying Medal, thanks to her helicopter flights. Reitsch successfully completed the series of indoor demonstrations to prove that the helicopter was fully controllable. But as she later wrote, "Exactly how deep an impression my flight with the helicopter had made on the world at large I was not to realize till many years later, in 1945, [when] I came across an American soldiers' magazine....The first thing that caught my eye was my name and then I saw that it contained an article describing in popular terms my flight with the helicopter."

n February 1938, Reitsch would become the first person to fly a helicopter inside a building, Berlin's Deutschlandhalle. She had previously been called on to demonstrate the Fa-61 to American aviation legend Charles Lindbergh at Bremen, whom she afterward described as a man "whose simplicity of manner won all hearts wherever he went." She also became the first woman to be awarded the Military Flying Medal, thanks to her helicopter flights. Reitsch successfully completed the series of indoor demonstrations to prove that the helicopter was fully controllable. But as she later wrote, "Exactly how deep an impression my flight with the helicopter had made on the world at large I was not to realize till many years later, in 1945, [when] I came across an American soldiers' magazine....The first thing that caught my eye was my name and then I saw that it contained an article describing in popular terms my flight with the helicopter."

Reitsch visited the United States in August 1938 to make an appearance at the International Air Races at Cincinnati. She enjoyed the trip, even though she did encounter some anti-German sentiment. Her demonstration of Hans Jacobs' aerobatic glider, the Habicht (goshawk), was received with great applause by the Americans.

War Years

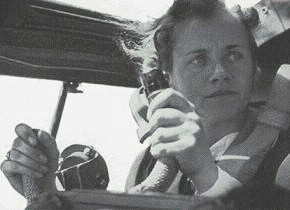

P ictured right: Reitsch in Libya, 1939

ictured right: Reitsch in Libya, 1939

In 1939 she suffered through a three-month bout with scarlet fever, followed by muscular rheumatism. But she recovered and went right back to work, later undertaking a very dangerous assignment involving the development of barrage balloon cable shears for German bombers. By 1942, she was test-flying the bullet-shaped Messerschmitt ME 163 Komet, driven by a liquid hydrogen Walther rocket engine.  But there were a few problems. Standing at only five foot one, the cockpit was not built for someone her size. It was hard for her to reach the rudder pedals, plus she could not use the shoulder harness because of needing to lean forward to operate the controls.

But there were a few problems. Standing at only five foot one, the cockpit was not built for someone her size. It was hard for her to reach the rudder pedals, plus she could not use the shoulder harness because of needing to lean forward to operate the controls.

In her fifth flight in the Komet, everything was fine until Reitsch went to drop the takeoff undercarriage and it failed to fall away. The plane began to shudder and despite her and the tow-plane pilot’s best efforts of maneuvering, the undercarriage would not dislodge. To Reitsch it was unthinkable to abandon such an expensive aircraft, so she decided to try to land it without knowing how the landing gear had configured itself. She brought it down into a plowed field near the runway, but the plane flipped over, catapulting Reitsch’s face into the instrument panel. She tried to get out but couldn’t, so - feeling she might not survive to give her report - she spent the time sketching and labeling the details of the accident. Moving the clipboard because blood was splashing onto it from her face, she noticed a rubbery object in her lap and picked it up. It was her nose.

Reitsch’s injuries were extensive. She’d fractured her skull in six places, smashed the bones of her detached nose irretrievably, displaced her upper jawbone, broken several vertebrae and bruised her brain severely. She nearly died.

Four days later, Reitsch was awarded a special diamond-encrusted version of the Gold Medal for Military Flying by Reichsmarshall Göring. But it took five months of plastic s urgery and neurosurgery to repair her face, and five more months for Reitsch to recover from physical weakness and normal mental depression. She put herself on a regimen of tree and roof climbing to restore her sense of balance. When Adolf Hitler himself awarded Hanna Reitsch the Iron Cross of the Knight’s Cross, First Class, the only woman ever to receive this medal, he forbade her to ever again attempt such a foolhardy feat.

urgery and neurosurgery to repair her face, and five more months for Reitsch to recover from physical weakness and normal mental depression. She put herself on a regimen of tree and roof climbing to restore her sense of balance. When Adolf Hitler himself awarded Hanna Reitsch the Iron Cross of the Knight’s Cross, First Class, the only woman ever to receive this medal, he forbade her to ever again attempt such a foolhardy feat.

Before she had doctor’s permission, Reitsch began to fly again, starting with gliders and moving on to powered aircraft and strenuous aerobatic maneuvers, until she was satisfied her skills were as good as ever. She learned the details of the pulse-jet powered V-1 buzz bomb and the V-2 ballistic missile programs run by General Walter Dornberger and Wernher von Braun. She was present but unhurt in the first Allied bombing raid on the Peenemünde-West complex, which left it a pile of rubble.

Operation Self-Sacrifice

Shortly thereafter, she met with a group of friends in Berlin who discussed what they could do to save Germany from a slide into defeat. The group came up with aerial strikes on Allied targets carried out by suicide bomber pilots, and called their concept Operation Self-Sacrifice.

When Reitsch discovered she was no longer allowed to fly the ME 163, which was currently in production, she accepted a request from her long-time friend Ritter von Greim to visit him on the Russian front to boost the morale of the troops. Seeing the conditions there, the bloody realities of the war were driven home to her and she determined to press the idea of the special corps of suicide pilots. Early in 1944 she was able to bring up the subject of Operation Self-Sacrifice with Hitler himself when she was in Berchtesgaden to receive her Iron Cross. Hitler dismissed the idea, believing it would not be an effective use of Germany’s limited resources, and diverted the conversation, but we know how persuasive Reitsch can be. He eventually gave permission for experimental work only.

Reitsch formed an alliance with SS-Hauptsturmführer Otto Skorzeny, a noted commando, and another test pilot, Hauptmann Heinrich Lange, and the three sought to form a unit of Selbstopfermänner (self-sacrifice men) who would offer their lives if necessary to accomplish their mission. Adolf Hitler had insisted that the pilots be given some means of escape, and the Germans went to great lengths to distinguish their Selbstopfermänner from the Japanese Kamikaze pilots, whose cockpits were sealed close before take-off.

The project was given the code-name Reichenberg and within 14 days, three training models and the operational model had been designed and put under test. The Fi 103R was to be carried by a parent aircraft and released near the target. The pilot would then take over and guide the bomb to a dive toward the target, and he was to detach the canopy and bale out just before impact. The canopy, however, would very likely block the pulsejet inlet and reduce the chance of pilot survival to almost zero.

The planners hoped to use the V-1 guided glider bomb then entering operational status. In the course of test flights, Reitsch identified some problems and contributed to improving the accuracy of the V-1. It’s interesting that the official reports say Hanna Reitsch had the special physical ability to withstand tremendous pressures and thus was well suited to solve the special problem with the V-1 rocket. She was the only person to successfully fly it. She was designated an instructor of volunteer pilots in the Leonidas Squadron; this was dangerous work and there were deaths and injuries. Reitsch encountered numerous difficulties with the project and it never took off even though some 70 pilots volunteered for training, largely because of the prevailing attitude among high-ranking Nazis, including Göring, that the very idea of suicide-pilots was “un-German” and went against the grain of the German psyche.

It wasn’t until April 1945, with the Luftwaffe under pressure from every side, that Göring made the decision to authorize suicide missions. Volunteer pilots would ram the remaining ME 109's into Allied bombers. The first mission was code named "Werwolf" and the Führer gave the go ahead. Several hundred volunteers were given ten days of ideological training at Stendal. On April 7, "Werewolf" was executed -183 fighters, the bulk of them Me Bf 109G, challenged some 1,300 American bombers, accompanied by about 850 fighters. Seventy pilots died; only 15 planes survived, with only a few succeeding in smashing into the enemy bombers before being shot down. On April 16, as the Soviets pushed across the Oder River, sixty more suicide pilots crash-bombed their planes into the Oder bridges in a desperate attempt to save Berlin.

In the Bunker

The last months of Reitsch’s wartime service involved flying wounded soldiers into hospital airstrips, carrying urgent dispatches by air and surveying air routes into the rubble of Berlin. Then, on April 25, 1945, Reitsch’s friend Col. General von Greim, knowing of her experience and expertise flying around the capital, asked her to fly him into Berlin in a helicopter, as he had been summoned to a meeting with Hitler. Assuming they would never return from this flight, he first asked her parent's permission, which they gave. She traveled to Salzburg where they had retreated to say goodbye to them, and to others of her family. Arriving at Rechlin Air Base, she learned the situation in Berlin had worsened, plus the helicopter they had intended to use had been destroyed. Another pilot was to fly von Greim to Gatow in a single seater Focke-Wulff 190, but Reitsch questioned how he would get from there to the Reich Chancellery. She asked if she could be crammed into the back of the plane, so that, with her knowledge of the Berlin center, she could see that von Greim found his way to the Chancellery. This was done and she describes it as the most terrifying plane ride of her life, as she was completely immobile and sightless the entire time.

Upon landing, they learned that all the approach roads into the city were in the hands of the Russians. They finally decided to try to fly into Berlin in a Fiesler Storch (stork) and land at the Brandenburg Gate. At 6 p.m. they took off in the only Fiesler Storch left, with Greim at the controls and Reitsch crouched behind him. As a hail of Soviet anti-aircraft fire hit the engine and fuel tank, an armor-piercing bullet smashed Greim's right foot, and he passed out. Reitsch, using only hand controls, managed to successfully land the Fieseler on the boulevard before the Brandenburg Gate, and they both made it into Hitler's bunker.

Now began events even more dramatic and historic than what Hanna Reitsch had already experienced in her event-packed life. Reitsch and Greim remained in the bunker until early morning April 30. Present, along with Hitler and Eva Braun, were the Goebbels with their six children; State Secretary Naumann; Martin Bormann; Hewel from Ribbentrop's office; Admiral Voss as representative from Dönitz; General Krebs of the infantry and his adjutant Burgdorf; Hitler's personal pilot Hans Baur, and another pilot Bätz; SS Obergruppenfuhrer Fegelein as liaison with Himmler; Hitler's personal Physician, Dr. Stumpfegger; Oberst von Below, Hitler's Luftwaffe Adjutant; Dr. Lorenz representing Reichspresse chief Dr. Dietrich for the German press; two of Hitler's secretaries, and various SS orderlies and messengers.

Outside, SS elite troops were committed to guarding Hitler to the end. Inside, after Greim’s foot was operated on by Hitler’s physician, the Führer came into the room and expressed deep gratitude for his coming, saying that even a soldier had the right to disobey an order when everything indicates it would be futile and hopeless. Hitler then informed Greim of Göring’s betrayal and Greim’s succession to commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe. He said to Greim, “In the name of the German people I give you my hand.”

Shocked, both Reitsch and Greim asked to stay with him in the bunker to the end. Hitler agreed at the time and, later that night, according to Reitsch’s Allied interrogation report, gave Hanna a vial of poison for herself and Greim, as everyone else already had, saying "I do not wish that one of us falls to the Russians alive, nor do I wish our bodies to be found by them.” Reitsch, sobbing, begged her Führer to save himself and not deprive the German people of his life. That, she said, is the will of every German. Hitler answered that, “as a soldier, I must obey my own command that I would defend Berlin to the last.” He explained other things, and told her he still had hope that Wenk’s army could arrive from the South, but this was in case it came to the worst.

Hanna returned to Greim’s bedside and they decided together that should the end really come, they would quickly drink the contents of the vial and then each pull the pin from a heavy grenade and hold it tightly to their bodies.

On the 27th , Obergruppenführer Fegelein disappeared. Shortly thereafter, he was captured on the outskirts of Berlin disguised in civilian clothes, claiming to be a refugee. Hitler ordered him shot, but this event caused some doubt as to Himmler’s position. And, indeed on the 28th, a telegram arrived which indicated that Himmler had joined the traitor list by contacting British and American authorities through Sweden to propose a capitulation. This was a personal blow to Hitler, and was followed by the news that the Russians would make a full-force attack on the Chancellery on the morning of the 30th.

Just after midnight on that day, Hitler came to Greim’s room and ordered him to return to Rechlin to muster his planes to destroy the Soviet positions from which they would attack the Chancellery, and also to stop Himmler from succeeding him as Führer. Greim and Reitsch both protested that they would never reach Rechlin, the attempt was futile, but after a bit Greim agreed that every effort must be made, if just to give the light of hope to those in the bunker. Hanna, though, went again to Hitler and begged that they be allowed to stay and die with him. According to her, he just looked at her for a moment and said, “God protect you.”

So, preparations being quickly made, thirty minutes after Hitler gave the order, they left the bunker. They took with them two letters to Magda Goebbels’ son who was then in an Allied Prisoner of War Camp and a diamond ring given to Hanna by Frau Goebbels, to wear in her memory. Greim was urged by von Below to get out so that he could “tell the truth to our people” and “save the honor of the Luftwaffe.” SS men brought up a small armored vehicle which took Reitsch and Greim to where an Arado 96 was hidden, brought by the same pilot who flew them to Gatow. Reitsch said later she was certain this was the last craft available, and it was highly unlikely another could have gotten in again, even for Hitler.

Resistance and Capitulation

Now began another amazing adventure. The plane took off during a lull, the pilot circling until they reached a cloud bank that protected them, after which they emerged into a clear night sky. In 50 minutes, they reached Rechlin; then, after conferring with what remained of the Operations Staff, flew, with Reitsch as pilot in a small Buecker plane, to Ploen to confer with Doenitz. In response to Greim’s order, the sky was soon filled with German and Russian planes. Landing at Lubeek, they had to auto to Ploen, where they found Doenitz knew nothing of Himmler’s actions. From there, they went to find Keitel, who on May 1st gave them the news that Wenk’s army had long been destroyed or captured, and that he had sent word to that effect to Hitler the day before, on April 30. Greim and Reitsch now fully expected the suicide plans had been put into operation.

That evening, the announcement of Hitler’s death was made and that Admiral Doenitz was his successor. After another short trip to Ploen, they flew in a Dornier 217 to Koeniggraetz where Greim lay in hospital for four days while events moved swiftly. On May 7th news reached him that capitulation would probably take place on the 9th.

They left that night, and after crash landing in a field near Graz because of flak, took off again for Zell am See in search of Field Marshal Kesselring. By the time they got there, they learned Germany had already signed an unconditional surrender; Greim's command was at an end.

They flew to Kitzbühl on the morning of the 9th and reported to American Military authorities shortly thereafter. Greim was under treatment until the 23rd of May when he was taken to Salzburg, Austria prior to being taken on to Germany as a Prisoner of War. He committed suicide with Hitler's poison capsule in Salzburg on the night of the 24th of May, rather than submit to the victors’ torture tactics. Hanna was under extended interrogation by the Americans and then held in prison for 15 months, during which time she stubbornly refused offers to follow Wernher von Braun and others to America. While incarcerated she learned that, because of rumors that Germans from Silesia were to be returned there under the Russians, her father had killed her mother, her sister, and her sister's children, before turning the rifle on himself. Hanna, who had endured so much, endured this also.

They flew to Kitzbühl on the morning of the 9th and reported to American Military authorities shortly thereafter. Greim was under treatment until the 23rd of May when he was taken to Salzburg, Austria prior to being taken on to Germany as a Prisoner of War. He committed suicide with Hitler's poison capsule in Salzburg on the night of the 24th of May, rather than submit to the victors’ torture tactics. Hanna was under extended interrogation by the Americans and then held in prison for 15 months, during which time she stubbornly refused offers to follow Wernher von Braun and others to America. While incarcerated she learned that, because of rumors that Germans from Silesia were to be returned there under the Russians, her father had killed her mother, her sister, and her sister's children, before turning the rifle on himself. Hanna, who had endured so much, endured this also.

Rebuilding her life

With her usual determination, Reitsch tried to rebuild her life. Like all Germans under the new occupation, she was forbidden from flying until the 1950’s. She lectured, wrote articles, gave newspaper interviews, and helped sick and needy people in Frankfurt while she dreamed of flying again. Still the disciplined role-model, she ran and did yoga exercises daily, and played the piano. She wore her Iron Crosses (she had received both first and second class) proudly and wrote her memoirs, Fliegen, mein Leben (1951), which were translated in 1954 as Flying is My Life. In this book she presents herself as a patriot, and makes no moral judgments about Hitler and Nazi Germany.

When allowed to fly again, Hanna returned to her true passion, gliding. Proving that she had not lost her touch, she won a bronze medal as the only female competitor at the international gliding championships in Madrid in 1952 ... became the German sailplane champion in 1955 ... flew as a research pilot ... and set a women’s glider altitude record of 7,000 meters in 1957. But the following year she found herself a victim of her past when Poland refused her a visa to participate in the world glider championships there.

She established a gliding school in India, addressed the Congress in New Delhi, and took Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for a sailplane ride. She also spent four years setting up a national gliding school in Ghana, where her students called her “Mother,” and was received at the White House by President John F. Kennedy. She was named pilot of the year in the United States in 1972. After a life of truly incredible adventure, honors, sacrifice, and heart-breaking losses, Hanna Reitsch died peacefully in her bed in Frankfurt, Germany, one year after setting a new women’s distance record in a glider. The year was 1979; her age was 67; cause of death, heart failure.

She has described in a memoir what she calls ‘my offence’: "I was a German, well known as an aviator and as one who cherished an ardent love of her country and had done her duty to the last."

Hanna Reitsch was interviewed and photographed several times in the early 1970's in Germany by US investigative photo journalist Ron Laytner. At the end of her last interview she told Laytner:

"When I was released by the Americans I read historian Trevor Roper’s book, The Last Days of Hitler. Throughout the book like a red line runs an eyewitness report by Hanna Reitsch about the final days in the bunker. I never said it. I never wrote it. I never signed it. It was something they invented. Hitler died with total dignity.

"And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can't find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power."

Then she uttered the words that for so long kept her out of the history books.

"Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don't explain the real guilt we share - that we lost."

- 10177 views