By Carolyn Yeager

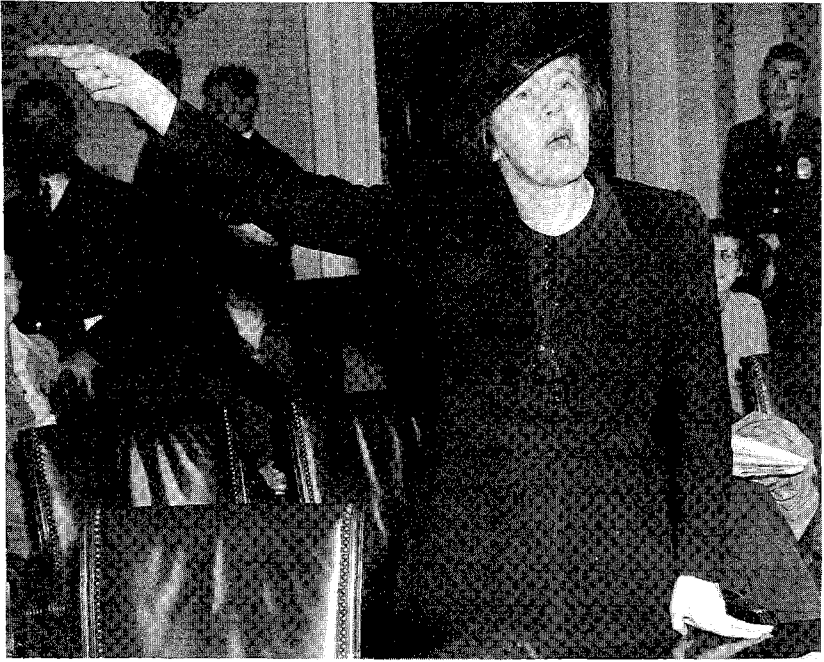

February 1941: Barbara Withrop gives last-minute instructions to volunteers departing for Washington D.C. to protest Lend-Lease.

In the 1930’s, America was in a national debate over liberal/conservative and pro-war/anti-war policies. Ultra-conservative women leaders emerged and in 1939 organized opposition to America’s involvement in World War II as mothers. At its peak in 1941, this confederation of women’s groups had a membership of six million! Can we even imagine anything like that today?

Though these women were well known in their day, they have been blotted out of mainstream history. They are not part of the story of this country that we have been told and that we share as a people. I found no pictures and very little information for these women on Wikipedia or other Internet sites, except for Elizabeth Dilling. The information in this article was mostly gathered from the 1996 book by Glen Jeansonne, Women of the Far Right (University of Chicago Press). Apart from this book—which is highly biased against the beliefs which motivated the mother’s movement—for all practical purposes, most of these women never existed. Jeansonne is unable to resist copiously adding his own liberal, feminist, philo-semitic criticisms of the mother’s movement figures. At the end of the book, he divulges:

As a Jew, a supporter of the New Deal and Democratic presidential candidates, the husband of a feminist theologian, and the father of two daughters, I have no sympathy at all for the far right. I have devoted much of my academic career to exposing bigots and anti-Semites.

Even though he approaches this book as an expose of those he despises, I recommend it because of all the research it contains which informs us about the period.

At the time in question, the twins of Communism and Feminism, under the guise of equal rights, were growing ideologies in America, promoted for the most part by Jewish organizations using both overt and covert means. Large numbers of Jews had arrived in America with the wave of immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. Most were without much education or wealth, but they immediately and almost unanimously emphasized higher education for their children. Many began to make dramatic success in business and finance, while others began taking control of publishing houses, newspapers and the entertainment industries. Laissez faire economic conditions and a booming economy made business opportunities boundless. Also aiding the upward trajectory of Jews was the climate of broadening democracy and greater social, political and economic freedom.

Resistance to such rapid changes came from many areas, including the Church and the Republican Party of that day, but the seeming economic benefits of liberalism had too strong an appeal. When Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1933, Jewish influence in government and politics increased dramatically. They supported Roosevelt financially and with their media, and he, in turn, was sympathetic to them, their liberalism, and even their communism.

The women involved in the mother’s movement shared certain traits: they took motherhood seriously and took themselves seriously as mothers. They believed they had not only the right, but the obligation to protect their sons and daughters from government and other outside abuse. They became warriors in the cause of protecting their families and, as they saw it, their nation. For them, the two were linked.

These women tended to be avowed Christians. They were nationalistic and patriotic, anti-Communist and pro-capitalist. They supported sexual abstinence before marriage and upheld the traditional nuclear family, which in their eyes included a strong Father presence. These women didn’t set themselves off against men; men weren’t “them,” they were part of “us.” Unlike the feminists, they saw gender not as a single issue, but as a part of larger socio-political concerns. Only mothers, they believed, could save their sons from the slaughter in the war that was impending.

In that day, they had some media support which has since disappeared. William Randolph Hearst (Los Angeles-San Francisco) and Robert McCormick (Chicago) headed non-Jewish newspaper empires that used their newspapers to promote opposition to U.S. entry into the war. The newspapers provided positive press to the mother’s movement for years; even so, no financial link between the papers and the movement has ever been shown.

Left-wing critics have to admit that the influence of the mother’s movement hampered Franklin Roosevelt’s attempts to unify the country in preparation for war. The mothers published materials, testified before Congress, picketed government centers, and aided in political campaigns. It goes without saying that even though only a few top leaders are featured in this article, every woman who played an active role or was even a member of one of the several organizations stood up for the values of White America in spite of the criticisms of the internationalists. This criticism has become institutionalized today, as is illustrated by the personalities and their comments immediately below.

Modern militant feminists have nothing good to say about these women. Jewish communist Gerda Lerner (pictured below left) stated that "these sorts of women" have internalized the idea of their inferiority, and that this has led them to participate in their own subordination.

Jew Hester Eisenstein (center), who calls herself a “socialist, antiracist, antihomophobic feminist” and globalist, says that they have been brainwashed to believe they need men to protect them. Andrea Dworkin, also Jewish, (her picture, right, is sufficient description), calls them reprehensible. These three women all hold professorships at universities and write books. Here are some quotes from them.

Lerner: “Maternalist theory is built upon the acceptance of biological sex differences as a given” which she rejects.

Eisenstein: Contesting that mothering is instinctive, “Politically, the right not to become a mother was central to feminist analysis.”

Dworkin: Saying praise of motherhood is an insult and a tool to keep women down, “Precisely because she is good, she is unfit to do the same things (as men).”

~~~~~~~~

Frances Sherrill, Mary Sheldon, and Mary Ireland—three California mothers of draft-age sons—formed the first mothers’ organization in 1939, just after Germany marched into Poland and Britain declared war on Germany.

They named it the National Legion of Mothers of America (NLMA) and its purpose was to oppose the use of United States troops except for defending this country from attack. By the end of the first week, ten thousand women had joined up, and by December the NLMA had been organized in 39 states. Mrs. Henry W. Hartough, chair of the Chicago unit, predicted that membership would reach one million in the Midwest within a year; a short time later, she claimed to have met her goal. One of the new recruits was quoted as saying, “I have a 21-year-old son and I am going to fight for him. It was too much trouble to bring him into the world and bring him up all these years to have him fight the battles of foreign nations.” By 1941, the NLMA claimed four million members.

Its emphasis was on grass-roots enlistments more than on rallies or marches. Small local groups elected a leader, and seven leaders constituted a patrol. Patrol reps created community councils that elected state councils, which elected a national executive committee. Meetings were held in schools and churches; volunteers were sought as speakers; funding came from donations, subscriptions to the NLMA newspaper, the “American Mothers National Weekly,” and the sale of pins.

National credibility was enhanced when the well-known, popular novelist Kathleen Norris became president. Norris was a pacifist, anti-communist and opposed capital punishment. She worked for the election of Wendell Willkie and the defeat of the selective service bill. When dissension based on philosophical differences emerged among certain key chapters, Norris felt unable to keep control. She resigned as president at the first annual NLMA convention in April 1941, though she remained active in the movement.

The convention delegates, faced with the splintering of their organization, voted to establish an executive committee to coordinate three groups: the National Legion, the Mothers of the U.S.A., and the Women’s National Committee to Keep the U.S. Out of War. Frances Sherrill led the first group; the second had ties to Father Charles Coughlin and Elizabeth Dilling in the midwest, while the third was founded by Cathrine Curtis, a New Yorker and friend of Dilling. Curtis was elected chair of the coordinating committee. In September, three months before Pearl Harbor, the coalition held a conference endorsing resolutions calling for neutrality, repeal of the Lend-Lease Act, impeachment of Roosevelt and the release of all draftees from the Army.

Elizabeth Dilling (pictured right) was the most prominent woman to emerge on the far right during those years. She described herself as a “super patriot,” and said that the real threat in Europe to us wasn’t fascism but communism. Dilling claimed that the “interracial idea,” as she referred to it, was one of the strongest dogmas of socialism-communism; that the left promotes interracial sex, and that if they get their way the races will be molded into “one big mass.”

Elizabeth Dilling (pictured right) was the most prominent woman to emerge on the far right during those years. She described herself as a “super patriot,” and said that the real threat in Europe to us wasn’t fascism but communism. Dilling claimed that the “interracial idea,” as she referred to it, was one of the strongest dogmas of socialism-communism; that the left promotes interracial sex, and that if they get their way the races will be molded into “one big mass.”

Dilling traveled extensively in Europe, including touring the Soviet Union in 1931—where conditions of poverty and filth appalled her—and to Germany in ’31 and again in ’38, where she noted great improvement in all social conditions and human happiness under National Socialism. Dilling contended that the left had duped everybody into seeing fascism as the big enemy when in fact it defended property, supported religion, promoted class harmony, battled communism, and presented no threat to us. Dilling warned that getting into the European war on the side of the communists in the Soviet Union was joining forces with the wrong side, and that in any case sending our boys across the ocean to fight in a European war would result in young lives being lost, disruption to family life, and a strain to the social fabric of this country.

Dilling was hostile to the woman’s movement on the left, which, she argued, had “tried to get women enthusiastically to prefer bricklaying to feminine pursuits.” She explained her increasing hostility to Jews by saying that “no one with open eyes can observe a Red parade, a communist, anarchist, socialist, or radical meeting anywhere in the world without noting the prominence of Jewry.” After reading a book written by Jewish atheist anarchist Emma Goldman (left),  Dilling asked, “Have women like me, who believe in beautiful Christian ideals, the right to sit in their rose-shaded living rooms … while the Emma Goldmans fill the platforms with their dirt and anti-American ideas?”

Dilling asked, “Have women like me, who believe in beautiful Christian ideals, the right to sit in their rose-shaded living rooms … while the Emma Goldmans fill the platforms with their dirt and anti-American ideas?”

Dilling toiled from early morning to midnight every day of the week at the cause she had taken to heart. She was assisted by her husband and had the support of her two children. Dilling wrote and toured the country tirelessly, and by 1939 audiences for her lectures and speeches had grown from hundreds to thousands. She led a parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C. in opposition to the Lend Lease Act. Over six hundred women marched in twos and carried banners that said “Kill Bill 1776, Not Our Boys.” A mass rally followed the march.

She organized a demonstration of twenty-five women outside of the office of a senator who was reputed to want the war. When the women sat down and refused to leave, Dilling and one other woman were arrested and the others ejected from the corridor. Dilling was later convicted of disorderly conduct for the incident.

She was also arrested and brought to trial under the Smith Act—which was later found to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court—for saying things like, “Any professed servant of Christ who could aid the church-burning, clergy-murdering, God-hating Soviet regime belongs either in the ranks of the blind leaders of the blind or in the ancient and dishonorable order of Judas.” The case was eventually dismissed, but it did tie up her time and drain her financial resources as she had to come up with legal fees and the other costs of a trial far from home.

After the war, Dilling kept right on going, crusading against communism, racial integration, the income tax, and the growing power of the federal government until her death in 1969.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cathrine Curtis (no picture found) was considered to be the most effective organizer among women of her ideological stripe during these years, and she became the leader of the coalition that included the National Legion of Mothers of America. A highly intelligent and private woman, the only child of wealthy parents, she learned financial skills from her speculator father and became rich in her own right through investing. Tall, slim and confident, she went from a career in Hollywood as an actress and producer, to broadcasting her own twice-weekly radio program from New York City, Women and Money, throughout 1934, in which she encouraged women’s financial independence and legal equality. She believed knowledge of finance was as important as knowledge of home economics for women. When she began denouncing Roosevelt’s New Deal as a betrayal of George Washington’s policies, her sponsors terminated the program. This angered her loyal listeners, who sent her contributions and invitations to speak. As a result, she founded Women Investors in America in May 1935, and later, Women Investors Research Institute, advocating anti-New Deal conservative economics and women’s rights. By 1939, membership in Women Investors had grown to 300,000 women in 28 states. Her organization sponsored talks and issued pamphlets and books, including Women and Money, Women and Taxes, and Women and Utilities.

For Curtis, it was not about helping women to achieve independence of men or family but rather of guarding and augmenting the family pocketbook. She thought woman’s financial expertise could guard the nation’s pocketbook as well, and thus serve as a buffer against communism. She proclaimed, “Woman, through her great ownership of insurance, trust funds, stocks, savings accounts, and homes, is the greatest capitalist in the world. We must mobilize to save this capitalism!”

In 1937, Curtis parlayed the organizational apparatus of Women Investors to spin off the Women’s National Committee for Hands Off the Supreme Court, which opposed FDR’s court-packing plan. Accompanied by fifty women wearing silk badges, Curtis testified before a Senate subcommittee, saying the measure encouraged contempt for the judiciary. She filed a petition containing 25,000 signatures opposing the proposal. Idaho Senator William Borah later congratulated Curtis for helping defeat the plan.

In Sept. 1939, after polling hundreds of women and finding many were ignorant of the issues, Curtis announced the creation of the Women’s National Committee to Keep the U.S. Out of War. She wanted women to think about and discuss foreign policy.

Curtis developed ties with other women’s organization leaders, including Rosa Farber of Mothers of the U.S.A., Beatrice Knowles of United Mothers of America, Marguerite Morrison of American Women Against Communism, and Marie Smith of the women’s division of the No Foreign War Committee. She also worked closely with Elizabeth Dilling, until the two broke over tactics in fighting Lend-Lease. Dilling wanted to employ confrontations and demonstrations, but Curtis thought this was counter-productive, causing Senators to close their doors to calls by women. Curtis preferred to work behind the scenes, directing groups of women to meet with senators privately, followed by letters. Rosa Farber publicly complimented Curtis by stating, “I regard Mrs. Curtis as the most capable woman in the country today. She not only knows politics, but she knows Washington.”

In April 1941, Curtis composed and circulated a “Mothers’ Day Petition,” asserting that men had no right to destroy life without the consent of women; that war resulted because mothers were not included in the peace process. In July, she appeared again before a Senate panel to oppose a bill that would authorize the president to conscript private property during a military emergency. But after the passage of Lend-Lease, the movement’s appeal diminished, and after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Committee to Keep the U.S. Out of War disbanded.

Curtis, while probably the strongest organizer in the mother’s movement, was different from most of the other leaders, and rank and file, in that religion did not play a key role in her life or her message. To her way of thinking, financial values were more important for the stability of the individual than religious values. She communicated on an intellectual level rather than an emotional one. Despite her desire to see women succeed, she was highly critical of women like Eleanor Roosevelt – in fact, she hated Eleanor even more than she hated FDR.

~~~~~~~~~~~

L yrl Clark Van Hyning (right, appearing before a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago in 1942) created We the Mothers Mobilize for America, along with Lucy Palermo and Grace Keefe. This turned out to be one of the largest and most active mothers’ organizations, but didn’t enter the action until the debate over Lend-Lease. After Pearl Harbor, We the Mothers actually stepped up activity and continued on even after the war. Incorporated in February 1941 in Chicago, within months it claimed 100,000 members locally and 150,000 nationwide. Elizabeth Dilling and writer Barbara Winthrop were also involved in the organizing. A male auxiliary was called We the Fathers.

yrl Clark Van Hyning (right, appearing before a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago in 1942) created We the Mothers Mobilize for America, along with Lucy Palermo and Grace Keefe. This turned out to be one of the largest and most active mothers’ organizations, but didn’t enter the action until the debate over Lend-Lease. After Pearl Harbor, We the Mothers actually stepped up activity and continued on even after the war. Incorporated in February 1941 in Chicago, within months it claimed 100,000 members locally and 150,000 nationwide. Elizabeth Dilling and writer Barbara Winthrop were also involved in the organizing. A male auxiliary was called We the Fathers.

Organized by congressional district to influence political campaigns, the idea was to insert women in key organizations and “take them over.” Dues were twenty-five cents a year; a subscription to the professionally printed, monthly eight-page newsletter, Women’s Voice, was $2 per year. Funds were also raised by selling Christmas cards with religious and patriotic themes.

Van Hyning was the dominant figure from the beginning. Of Scotch-English ancestry, she was a descendant of a Revolutionary War general and an officer in the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution). A schoolteacher before marrying, she and her businessman husband lived in South America for more than a decade before settling in Chicago in 1933 with their three children. (Her son served in the army air corps during WWII.) She dressed fashionably, was intelligent, energetic, charismatic, and a forceful speaker. Her keynote address at the first national women’s peace convention, which she organized in 1944, brought her audience to tears. Also an effective writer, she wrote two or three long articles in each issue of Women’s Voice, the circulation of which grew to 20,000 by 1945, reaching every state and 47 foreign countries, with complimentary copies sent to each member of Congress. All work was done by volunteers.

We the Mothers conducted their political activities through neighborhood networks and weekly meetings, called “Get Together Parties,” held in members’ homes. The meetings featured prayer, spiritual talks and religious songs, with some groups even engaging in bible instruction. In the same spirit, Women’s Voice printed religious poetry and used religious metaphors and imagery. However, the chief concern was with British perfidy, the threat of communism, and Jewish international bankers who were blamed for getting the United States into the war. Guest speakers included such well-known figures as the aviatrix Laura Ingalls, Agnes Waters and Joe McWilliams. Van Hyning also organized speaker luncheons at local hotels to draw new members, often with local politicians or visiting women lecturers.

We the Mothers circulated recall petitions against members of Congress they blamed for getting us into the war. Van Hyning said she had been idealistic during World War I, working in a factory, donating her wages to the Red Cross, and buying War Bonds. Now she knew better, recognizing that the U.S. incited the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor; that it was the happiest day in Roosevelt’s life; and that “Wars are for profits—the profit is in the bonds. No bonds—no profit.”

After the battle against Lend-Lease was lost, We the Mothers distributed 30,000 cards entitled, “A Redeclaration of American Independence” for people to sign and mail to the president, asking for a constitutional amendment to require a public referendum to declare war. They launched a letter-writing campaign directed at parents of sons who had died on American destroyers, calling it “needless slaughter.” The letters were signed by Van Hyning and Keefe and urged the relatives to sue the president and secretary of war for damages. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox charged that We the Mothers were “part of an organized campaign to undermine civilian morale and the morale of the armed forces.” Van Hyning was undeterred.

We the Mothers also got into debate with influential liberal newspaper columnist Dorothy Thompson, questioning her patriotism and accusing her of being in the pay of the Communist Party. In turn, Thompson accused the mothers of being paid to spread dissension, and called them “black cockroaches who call themselves American mothers.” Keefe issued a statement that Thompson’s son was only 11 years old, and she knew he would not “be called upon to make good on her offer to give a million American boys to defeat Hitler.”

Van Hyning strongly opposed the Normandy invasion in 1944. A few weeks before the invasion she said, “Those boys who will be forced to throw their young flesh against that impregnable wall of steel are the same babies mothers cherished and comforted and brought to manhood. Mother’s kiss healed all hurts of childhood. But on invasion day no kiss can heal the terrible hurts and mother won’t be there. Mothers have betrayed their sons to the butchers.”

The first National Women’s Peace Convention, organized by Van Hyning and held at the Hotel Hamilton in Chicago, June 1944 (mentioned above), attracted 125 women delegates, and a few men, from 16 states. They adopted a resolution for an immediate armistice and a negotiated peace, which Van Hyning said was the only peace worth having. “Policing the world means that you will never have your boy at home – that is what dictated peace means, what unconditional surrender means.” (We have seen the truth of that, as we still have large military forces in Germany and Japan 60 years later.) Other resolutions were adopted to condemn the prosecution of patriots such as Dilling for sedition, and urging a cessation of immigration for ten years.

In 1945, We the Mothers attempted to prevent creation of the United Nations by traveling to San Francisco and trying to break into the organizing conference. When the second women’s peace conference met once again in Chicago, 200 delegates from 36 states, including 20 men, attended. Van Hyning delivered several speeches, in which she said it was up to women to save the country, and condemned the international conferences at Dumbarton Oaks, Bretton Woods, and San Francisco. The delegates adopted resolutions demanding immediate conversion of industry to civilian production, an end to rationing, abolition of the Federal Reserve System, a Constitutional amendment to limit private fortunes, and a pledge to investigate un-American textbooks in public schools.

In her comfort with Christianity, Van Hyning was similar to Dilling. However, she shared with Cathrine Curtis an interest in women gaining political power—a large part of the agenda of We the Mothers was to encourage women to run for political office, not only for their right-wing views, but just because they were women. She believed, along with Curtis, that women, partly because of their experience with raising children, were uniquely qualified to rule.

~~~~~~~~~~~

Agnes Waters, shown here testifying before the House Military Affairs Committee in Oct. 1942, opposing the lowering of the draft age from twenty to eighteen, did not lead a group but gained prominence as a spokeswoman and anti-Roosevelt commentator, protesting immigration, conscription and Lend-Lease. Working mostly alone out of Washington D.C. because her intense personality didn’t lend itself to working within groups, she nevertheless assisted the National Blue Star Mothers, the Mothers of the U.S.A., and We the Mothers Mobilize for America, in their efforts.

Agnes Waters, shown here testifying before the House Military Affairs Committee in Oct. 1942, opposing the lowering of the draft age from twenty to eighteen, did not lead a group but gained prominence as a spokeswoman and anti-Roosevelt commentator, protesting immigration, conscription and Lend-Lease. Working mostly alone out of Washington D.C. because her intense personality didn’t lend itself to working within groups, she nevertheless assisted the National Blue Star Mothers, the Mothers of the U.S.A., and We the Mothers Mobilize for America, in their efforts.

Born Agnes Murphy Mulligan in New York City in 1893, she traced her lineage to patriots who fought in the Revolutionary War and wrote the Bill of Rights, and even to British royalty as a direct descendent of King James II. Her father was class valedictorian at New York University Law School and a prodigy who entered high school at age 11. Her mother, Agnes Murphy, was also gifted, taking over her father’s tiny real estate agency in New York City and building it into one of the more successful firms in the city. She then entered NYU Law School and earned the first law degree ever awarded to a woman in the state. Her parents married in 1892, with her mother converting to Catholicism, and had seven children.

Agnes was educated by private tutors and read law in her father’s office, without earning a college degree. During World War I, she involved herself in women’s suffrage and the National Women’s Party. After the War, she married, but was widowed before 10 years passed. She then began selling real estate and did exceedingly well, earning $40,000 her first year and $130,000 her second. She went on to close millions of dollars in land deals.

In the mid-1930’s, Waters became involved in the nationalist movement, began to read about communism, testify before congressional committees, and attract women supporters for her campaigns. She became sensitive to the presence and influence of Jews and communists at rallies for the British and for the war. She circulated anti-war pamphlets and published The White Papers, consisting of antiwar speeches, news articles, letters she had written to public figures and newspapers, and her congressional testimony. She came to believe Roosevelt was a puppet of the Jews, possibly a Jew himself. After supporting him in ’32 and ’36, she now saw the Democratic Party in a different light because it refused her request to adopt a platform plank condemning communism. Even though she was seen by many as paranoid and worse, history has proven her to be uncannily correct in her perceptions. During the 1940 presidential campaign, she said it would be easier to shoot FDR and his cohorts “than to fool with the elections and a lot more certain of getting all traitors out of office because we are constantly betrayed by having stooges in both parties for candidates.” After December ’41, she said Roosevelt and the secretaries of state, Army and Navy had prior knowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack, which she called an “inside job.”

Between 1939 and 1946 she testified against repeal of the arms embargo, against Selective Service, against Lend-Lease, against the mobilization of labor, against extension of enlistments, and against the UN charter. She railed at Congressmen, “Are you all asleep at your posts? Why are you all so dumb and blind? Doomed! Just because you were so dumb or so stubborn you would not listen to me!”

In 1942, Waters announced she was running for both the Democratic and Republican presidential nominations in 1944. “It is high time the women of America took over the driver’s seat since the men have made a hell of a mess of things everywhere,” she said. And, “America was placed under the guidance and protection of a woman since her discovery by St. Christopher Columbus. The figure of a woman stands at all our mastheads above the stars and stripes. She is ‘Columbia, the gem of the ocean.’” When neither party nominated her, she ran a write-in campaign.

Waters had one success. In the summer of 1939, she and other leaders on the right worked to defeat the Child Refugee Bill that wanted to provide a haven in the U.S. for 20,000 German Jewish children over two years, apart from the German quota. Waters called them “potential communists” who could never become loyal Americans. The House Committee on Immigration amended the bill to count the twenty thousand children against the quota of adults, causing the bill’s sponsor, Senator Wagner, to withdraw it.

While all the mothers’ leaders were defiant and determined, Waters was even more so, becoming at times bombastic. Her tremendous energy seemed to need an outlet; religion and crusading gave her direction and satisfaction. At times, she tried the patience even of her female allies, although the rank and file delighted in her colorful words and actions. She appeared to be on good terms with her daughters, but they were not active in her crusades.

There was nothing like this confederation of mother’s groups in past history. They were vocal; they believed in themselves. While they did not affect many of the changes they worked so hard for, they did create quite a stir, and an opposition to those things we still oppose today. While some groups continued on even after the war ended, others came to a close after the Great Sedition Trial of 1944.

Elizabeth Dilling, her daughter, Elizabeth Jane, and her attorney and former husband, Albert Dilling, arrive at court for the opening of the sedition trial.

Elizabeth Dilling, her daughter, Elizabeth Jane, and her attorney and former husband, Albert Dilling, arrive at court for the opening of the sedition trial.

Dilling had the most active postwar career. For more than two decades she wrote about issues arising out of World War II and the communist conspiracy: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), foreign aid, the income tax, racial mixing, fluoridation of drinking water, and federal power. She backed Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s crusade against communist infiltration in the federal government and attacked both President Eisenhower and presidential candidate Sen. Barry Goldwater. She became an expert on the Talmud, which she discussed in her last book, The Plot Against Christianity, published in 1954. And she continued to write and send out the Bulletin, and write for other publications, including Women’s Voice. But eventually her work was slowed by poor health, and she died in 1966 at the age of seventy-two.

Cathrine Curtis remained outspoken for a time, opposing the UN, the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan and the Brown decision. She favored Sen. Joseph McCarthy, and when the Senate threatened to censure him she wrote a pamphlet entitled “Is McCarthy Censure Case Another Nuremburg Trial?” After that, she slowly withdrew from public life, returning to the world of business.

Van Hyning also remained active until the 1960s. Women’s Voice continued to be popular and to feature writers such as Dilling and Waters; as late as 1956, We the Mothers still had chapters in thirty-nine states. Her beliefs did not change. She opposed the Korean War and American soldiers fighting under the UN flag. In 1950, she and her mothers were volunteers in the campaign of Everett M. Dirkson, the Illinois Republican who defeated Lucas, the Democratic Majority Leader in the U.S. Senate, even though Van Hyning generally thought both political parties were equally bad. In 1952, We the Mothers held a nationalist convention in Chicago to prevent the election of Eisenhower, urging write-in votes for General Douglas MacArthur, with Joseph McCarthy as vice-president. Delegates adopted resolutions calling for an investigation of the Anti-Defamation League and for American withdrawal from the UN. In 1955, her son Tom was killed in a plane crash, and then in 1957, the death of Joseph McCarthy was hard for her. In 1962, she ceased publishing Women’s Voice.

Agnes Waters also carried the fight into the 1960s. She remained a popular speaker and continued to testify before Congress against every major foreign policy initiative the White House backed. In 1948 she made a second race for president as “the pistol-packin’ Mama.” She worked against the Marshall Plan, NATO, and the Korean War. In 1954, she announced in Women’s Voice that she would be a write-in candidate for president again in 1956, and urged women to run for office. She did the same for the 1960 election, but that was the last effort she was to make.

- 5031 views