Holo Frauds & Quacks

- 20157 reads

The Fifth Diamond: A Special Jewel in the Genre of Holocaust Horror Stories

- 26802 reads

By Carolyn Yeager

Copyright Carolyn Yeager, 2010

Irene Weisberg Zisblatt writes of swallowing the same diamonds over and over for a year in order to save all she has left of her family. What else does she say--and why is it not believable?

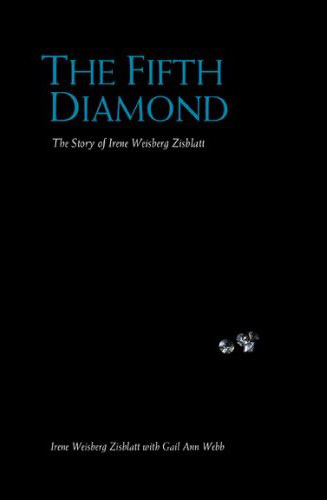

Zisblatt’s autobiography The Fifth Diamond (left) is endorsed on the back cover by motion picture icon Steven Spielberg with these words: "Irene Zisblatt eloquently speaks and inspires today’s generation with her personal story of remembrance and survival.” Remembrance —does that mean it doesn’t have to be true?

Irene Weisberg Zisblatt (Zeigelstein-Lewin-Stein) is a late-blooming “holocaust survivor-memoir writer” whose life story takes many mysterious twists and turns. She claims that in 1944, at the age of 13, she was deported to Auschwitz with her entire family, where only she escaped death in “gas chamber #2.”

For 50 years, she kept quiet about being a holocaust survivor; then she saw Steven Spielberg’s movie Schindler’s List and made the decision she must add her voice to the great cause of educating the world about The Holocaust.1 In that same year, 1994, she went as a survivor-mentor with a group of US Jewish teenagers to Auschwitz for the annual March of the Living. While there, she says, she remembered and relived her whole Auschwitz experience.2

In 1995 she was asked by Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah Foundation if they could videotape her holocaust testimony for their archival library. Her 3 ½ hours of answering questions and prompts by interviewer Jennifer Resnick is the basis for her being chosen as one of only five Hungarian survivors featured in Spielberg’s The Last Days, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Film in the year after its release, 1999.

At that time, she already wanted to publish a book and had been working on it, she says, since her son was thirteen. She asked Spielberg at the private premiere of The Last Days if the documentary would interfere with her book. He said no, but advised her to “not make it morbid, and don’t make it a 500 page book.”3 She said she followed his advice.

Zisblatt went to work for H&K Law Charitable Foundation as their “survivor-in-chief” who would have the final say on the winning essays in their national Holocaust Remembrance Project. During one of their teacher-training seminars, where teachers get free trips to learn how to teach the Holocaust from "experts" like Zisblatt, she met Gail Ann Webb, a Baptist (as Webb describes herself) high-school writing teacher from West Virginia. They talked about writing Zisblatt’s holocaust memoir.

Still, it took two more years before Webb wrote a first draft of the book as fiction. (Obviously that is what Webb understood it to be.) Zisblatt explained to her that holocaust survivor stories have to be first-person—non-fiction.4 It took a couple more years of changes and edits, but the final version of the book was published by Artists and Authors Publishers as “autobiography – non-fiction. It came out in 2008 and was quickly accepted in some school districts, including Webb’s own.

“The Fifth Diamond” is so named because the central theme of the book is four diamonds Zisblatt was given by her mother before they reached Auschwitz, and how she managed to hold on to them by repeatedly swallowing and retrieving them again after defecating. Yes, it’s quite improbable, but nevertheless this is what schoolchildren are given to believe—and they do believe it! The fifth diamond is Zisblatt herself, a brilliant light inspiring today’s youth.

The book is 160 pages of fiction, admittedly5 custom written for 13 and 14-year old “middle-school” students in our nation’s educational system. Middle school, the two to three years between grade school and high school, is when Holocaust studies are most heavily force-fed to American school children because of laws passed in many state legislatures by craven politicians hungry for Jewish votes and money, or fearful of Jewish media power. These legislators are also indoctrinated by the holocaust industry themselves, and accept on faith, i.e. without examination, that by turning a segment of their state’s school curriculum over to Jewish organizations pushing their religion-like holocaust narrative they are promoting racial and religious tolerance.6

The situation amounts to forced religious beliefs in that much of The Holocaust is necessarily explained as “miraculous happenings” that don’t follow reasonable expectations for how the world really works. These happenings are outside of time and space in the sense of special Acts of God. Zisblatt’s The Fifth Diamond is full of special Acts of God.

Perhaps this silly book could be ignored but for the fact it’s being read by thousands of young people in several states (Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia are three named by Zisblatt) during their typically 6-week-long “Holocaust Studies” unit, with the goal to extend its use into as many districts as possible. Zisblatt, who leaves a copy of her book in the library of every school at which she speaks, says she is on a mission to reach as many children as possible with her message of the holocaust7, so that “it will never happen again.” She is in a race against time, she says; at age 80, she speaks four or five times a week to whoever asks her, mostly in school auditoriums and classrooms, in community centers and universities.

Considering the reach of just this one small woman (Zisblatt is only 5’1” in height), who she is and how she evolved to be someone who could tell such an outrageous personal story, and be believed, cries out to be examined.

Irene Zisblatt talks with seventh-and eighth-graders at the Emma C. Attales School in Atlantic City after her presentation in April 2009.

I will be using as sources her book The Fifth Diamond [FD], published in 2008 by Artists and Authors Publishing of New York; her 3 ½ hour testimony videotaped on Oct. 25, 1995 for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation [ST]; Steven Spielberg’s 1998 academy award-winning documentary film The Last Days [LD], and a radio interview given by Zisblatt on 6-15-09 on the Internet-only Ithaca Press and Artists and Authors Publishers of New York Radio Hour, Artists First World Radio Network, Interviewer: Tony Kay [RI].

I am indebted to Eric Hunt for making these sources and many documents available on his (former) website. Without Eric’s brilliant original research and his courageous lawsuit brought against Zisblatt, Spielberg, Webb, and Artists and Authors Publishers, none of this would have gotten the attention it now has.

* * *

Who is she? She says in her Shoah Testimony (ST) she was born Irene Zeigelstein (she spelled it) in Poleno, a small town in the Carpathian Mountains, on December 28, 1930, eldest of six children in an Orthodox Jewish family. Is there any reason to question even these simple facts? YES.

On page 1 of her autobiography (FD) she writes, “My name was Chana Seigelstein,” and never refers to herself as Irene until she says she was given that previously unknown, new first name by the Immigration service before leaving Germany for the USA in 1947 at the age of 16 – two months short of 17. She also doesn’t give a birth date, only the imprecise statement in the Preface, “I was only 6 years old when The Third Reich started the invasion across Europe.”

Yet on the ship passenger manifest8 for her voyage to America in Oct. 1947, she is listed as Irene Lewin, 18 years old, traveling with her Polish husband Alter Lewin and his younger brother Elias.

Records for Irene Segelstein from the Red Cross tracing service and the Flossenbuerg Prisoner List show her born on Dec. 28, 1929, and the former says she was born in Sosnowitz, Poland. The Sharit haPlatah list has Irene Segelstein from Polene, born 1928. The World Jewish Congress Collection on Liberation lists Irene Siegelstein, Polena, Hungary as being 16 years old when she was liberated from Civilian Hospital, Volary, Czech Rep. in 1945. On the 2009 radio interview, she answered a direct question by interviewer Tony Kay that she was 14 when liberated, only she was alone in a forest.

In FD, Zisblatt writes that in Oct. 1947 she received an assignment from Immigration to board the ship “Marine Fletcher” in Bremen, Germany, and “by the end of October, the liner began it’s voyage.” The Marine Flasher did indeed sail from Bremen on Oct. 29, 1947, arriving in New York on Nov. 10, 1947 with Irene Lewin aboard, but no Irene Seigelstein.

Irene Lewin’s destination is listed as 42 Madden Terrace, Newark, New Jersey; the same for Alter and Elias Lewin. Yet Irene’s Uncle Nathan Siegelstein, who she says was her sponsor and whose home she immediately stayed in, lived in the Bronx, New York. In fact, on a 1941 draft registration card, he gave his address as 2141 Honeywell Ave, NY, Bronx NY.

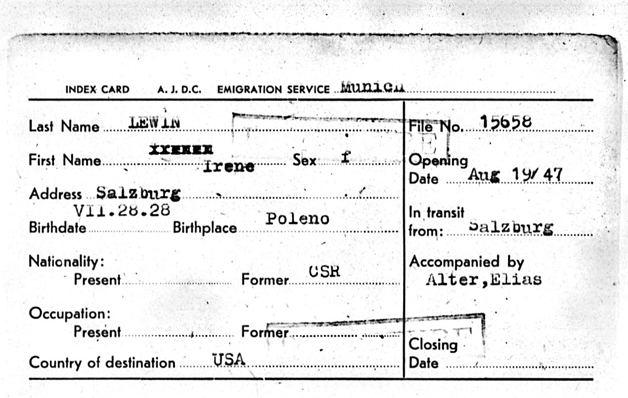

Supporting evidence that Irene Lewin on the ship passenger manifest is the same person as Irene Seigelstein is a DP Refugee Card for Irene Lewin issued in Munich, dated August 1947, which shows her born in Poleno in 1928 (this time on July 28 rather than Dec. 28). If the July date was correct, she would have been 19 years old in late October 1947, not 18; this indicates that July was probably a mistake and should have been December. (I now have confirmation from those who have access to this card that the birthdate was corrected on the back of the card, in pencil, to Dec. 28.) Her former nationality is shown as Czechoslovak (CSR) and she is in transit from Salzberg. How many Jewish girls born in tiny Poleno on the 28th of the month, in 1928, could be on that ship heading for New York? If there was another girl named Irene from Poleno, I’m sure our Irene would have found out and would talk about it … wouldn’t she?

Above: Displaced Persons refugee card for Irene Lewin, traveling with Alter and Elias; notice the original first name is crossed out. On the Ship’s Manifest for the Marine Flasher, the three are marked as traveling together, with Irene being Alter’s wife and Elias his brother. (credit: Eric Hunt)

Zisblatt writes in FD, pg 107: “When I arrived in New York, I first moved in with my Uncle Nathan and his wife, Helen.” On the following page, she writes, “I really enjoyed visiting my Aunt Fanny9 in New Jersey, so after a few months, I ended up moving in permanently with Aunt Fanny and Uncle Morris.”(These persons are all shown on the 1930 U.S. Federal Census.)

So just who was Irene Zisblatt during these years of her youth? Irene Zeigelstein? Chana Seiglestein? Then, Irene Lewin? Should we not want to know about this woman who is speaking to our schoolchildren 4 or 5 times a week and whose sado-masochistic, anti-German book they are reading? She even called herself Irene Stein. When her husband Herman Weisberg died in 1969, his obituary named her as the former Irene Stein.10

One more item of identity: In The Fifth Diamond, her "autobiography," Zisblatt devotes one line to a remarriage (of 10 years duration) that “didn’t work out” and says after Weisberg, "the love of her life," died, she "devoted her life to her children." I had to really dig to discover that in 1971, less than two years after Weisberg's death, she married Jack Zisblatt of Arlington, Texas—a salesman who regularly came to New Jersey on business. In November 1981, Jack filed for divorce in Tarrant County, Texas. Irene cross-filed, and also filed a third party action against a corporation owned by Jack at the time they were married. Irene failed in her attempt to convince the court that Jack Zisblatt's corporation was community property.11

Clearly, Zisblatt is selective in what she tells and what she doesn’t. Her life story is something she has carefully crafted to fit her new status as a film star and speaker on the lucrative holocaust survivor circuit.

Poleno cannot be found on any map, but it was firmly in Czechoslovakia from 1920 until 1939, when it was annexed back by Hungary. It had a large Jewish population; according to Zisblatt, 60 to 70 Jewish families, all Orthodox, attended the one temple, and there was only one Christian church (ST).

* * *

Her story really starts in 1939, when the Jews in Hungary begin to lose rights and entitlements, like her right to attend the public school (this appears not to fit the historical facts –cy). According to Zisblatt, this continued and worsened until 1942, at which time Jews fleeing Poland and Ukraine for Palestine began coming through their little town, some with terrible stories to tell. The one Zisblatt repeats in her Shoah testimony and public talks—and was used in The Last Days, not only by her but another survivor as well—is this: she overheard a man who spent the night at their house telling her father that “he saw Nazis tearing Jewish infants in half and throwing them in the Kneister river,” which she remembered from school was a river in Ukraine. The next day she asked her father about it and he told her that it wasn’t true, to forget it. In her book, Zisblatt changed that story to Germans killing Polish Jews, including women and children, and burying them in mass graves. (p 15)

She hasn’t listened to her father. Though it’s definitely not true, just another tale passed among Eastern European Jews at the time, she continues to repeat it to the children and teenagers to whom she speaks.

(Another atrocity story that she passes along is the one about SS men picking up Jewish children by the legs and banging them against the side of trucks. She both tells in The Last Days, and writes in Fifth Diamond that she saw through a crack in her barracks wall on her first night in Birkenau: “I saw trucks coming, and screams in the trucks, and I saw two children fall out of the truck, and the truck stopped and one SS man came out from the front and he picked up the children [by their legs] and he banged him against the truck, and the blood came running down, and threw him into the truck. So, that’s when I stopped talking to God.”)

From then on, she relates personal suffering that builds to the climax of her participation in a fictional Death March, followed by a fictional “liberation” by American General George Patton’s soldiers in a Czechoslovakian forest. The most notable contradictions that fill her story are the following:

Brother David dies at home and at Auschwitz

(Shoah Testimony) Zisblatt recounts that in 1943 she lost a brother, about 5 years old, who died of Scarlet Fever. In the same year, her two paternal grandparents also died of natural causes. Toward the end of her ST (@3hr6min), she says she would like to go back to her hometown to visit, because “my grandparents and my brother are buried there.”

(Fifth Diamond) Her brother David, who would have been “about 5” in 1943, is listed with her family members as perishing at Auschwitz in1944 at age 7 (page xvii). In her talks at schools and elsewhere, she thus makes the claim we hear from so many survivors: I lost my entire family at Auschwitz; I am the only survivor.

(Last Days) None of this is brought up in Spielberg’s film.

Friendly policeman sealed up their house

(ST) Around Passover time, the authorities are taking Poleno Jews from their houses and transporting them by rail to the nearby large town of Munkacs12, where a ghetto had been created. Their houses were then sealed up. Zisblatt says her family home was sealed up by a policeman friend of her father’s, with the family inside, in an attempt to fool the authorities and not be sent to the ghetto. She then blames the policeman for “squealing on them,” though it’s clear they could never get away with such a scheme.

(FD) The story of the policeman friend changes. He becomes a “Righteous Christian” with a Jewish wife (p. 21). He offered to seal up their house if they would take his wife in with them. Zisblatt says the wife was an assimilated Jew who had not known, before Hitler, that she was Jewish, and was deported with them. However, she is quickly forgotten in the narrative.

Confused about Passover and their deportation

(ST) The day after Passover, the police came in the early morning and broke down the door of their house. When asked about the date, Zisblatt says “I know it was on the 3rd, it was right after Passover, we didn’t have time to put away the Passover dishes; either April 3rd or May 3rd. Then she said, “Everybody (Jews) was home when we had Passover; the day after Passover everybody was gone, and the day after that, they got us.” Passover in 1944 was April 8th. Other’s accounts contradict the deportation date.12

(FD) They celebrate Passover in their sealed up home; the following night men broke their sealed door with an ax. This time she includes Nazi soldiers along with local policemen who “rushed up the ladder” to their attic, but she gives no dates.

(LD) She says “Two motorcycles was the whole Nazi regime that occupied our town.”

Different relatives in the Munkacs’ ghetto

(ST) When she, with her parents, uncle and siblings arrived at the Sajovits brickyard in the city of Munkacs, her mother’s mother was already there, with her mother’s two sisters and their families, and had made a space which they joined. She says they expected her father’s two cousins but they never arrived. Time spent in the brickyard was one week or less.

(FD) This time, they meet only her mother’s mother there, alone (p. 27). Her mother’s 5 sisters and brothers are listed on page xvii as perishing in Auschwitz but she writes nothing about them except for Bencie, who lived with the grandmother.

(LD) Only says it was raining a lot, and guards with big German Shepherd dogs on tight leashes walked around all the time.

Nowhere does she mention that the ghetto was administered by a Jewish Council, whose president was Sandor Steiner.

Diamonds rolled or sewn, many or just four?

(ST) She says as a kind of afterthought that before getting in the train cars leaving Munkacs, her mother “rolled” diamonds into the bottom of one of her skirts, and into her sister’s skirt. She says, “Of course, my sister was only 4 ½ years old, but I guess that was a way of preserving things. And she said to me, ‘Take care of this skirt. In case you have to work at a different place than I do, and you don’t have anything to eat, take out the diamonds to buy bread. But be very careful not to lose it.’” Now how do you ‘roll’ diamonds into the bottom of a skirt so that they won’t come ‘unrolled’ and be lost?

(LD) Her mother rolled diamonds into her skirt, but not into her sister’s.

(FD) It becomes quite a different story. Before Passover, while they are still at home, her mother calls her over and shows her four diamonds which she is going to sew into the hem of one of Chana’s skirts. These are “her mother’s diamonds,” the implication being this is all there is. She is told to guard them closely, never to sell them unless she is hungry – then she can use them to buy bread. All four diamonds go to her because she is the oldest daughter; none go to her sister.

Trip to Auschwitz

(ST) She says the train doors never opened, they never saw light, never got water; there was one pail for bodily elimination. Other survivors contradict this14 and describe stops for fresh water when the men actually got out and cleaned the pails. Said it seemed like forever, but does not give a specific time of travel. Nor does she mention her extended family being in the train.

(LD) She heard the “cattle car” doors bolt on the outside and they were locked inside for five days. Says, as above, they never opened the doors, never gave them any water.

(FD) The SS forced 100 people into each box car15 and gave them one small pail to use as a bathroom. Again repeats that it was a five day trip with no water, but others who made the trip said it was at most 3 days and they got two pails, one with water.

If it was really as Zisblatt describes it, no one would have survived the trip. But her whole family got off the train and were all able to move and behave quite normally. She herself goes through disinfection and doesn’t say that when under the shower she took the opportunity to parch her thirst. If she were telling the truth, dehydration would have been a major concern at the time.

Sees some or all of her family members going into gas chamber?

(ST) After they arrive at Birkenau she is separated from her mother and two youngest siblings, then sees them get into a black truck. She is led into a shower/delousing building, and after undergoing that process she emerges into a courtyard from where she again sees her mother and 2 siblings, now getting off the truck and walking behind a building that she learned later was the ‘gas chamber.’ (@1hr20min) Quite a coincidence that she happened to see them twice! She says she never saw her father and brothers again after they left the train.

(FD) Story changes. Her grandmother is now with them. In this version, before she enters the shower/delousing building, she watches the four of them walk past the trucks and enter a low bunker behind barbed wire fences. Then she sees her father and 3 brothers entering the same building! Now she has all 8 of her close relatives accounted for as being immediately gassed.

(LD) Speaks of being separated from her mother and two youngest siblings; no grandmother mentioned; no talk from her about the gas chambers in the film.

Swallowing her mother’s diamonds only once versus over and over again

(ST) When undergoing the initial disinfection process, she remembered the (unknown number of) diamonds rolled into her skirt and eventually put them in her mouth and swallowed them when she saw they were examining inside people’s mouths, and pulling gold teeth (@1hr18min). After this, there is no further mention of the diamonds in her ST; they are a thing of the past. In her mind at this time in 1995, she may have visualized them as tiny diamonds, which is why she could use them to “buy bread.”

(FD) She swallows the (four) diamonds for the first time and retrieves them the next day in the latrine, continuing to do this throughout her time of incarceration. Her insistence on keeping her mother’s diamonds is a major theme of the book. She also writes that the workers examining inside mouths during the initial disinfection “were removing fillings and crowns, and pulling gold teeth” (p. 36).

The pulling of the gold teeth is not believable, as it would have caused excruciating pain, a bloody mess and infection. Gold teeth were only removed from corpses.

(LD) She talks of her first time swallowing the diamonds, and says “The whole time I was in the camp, I swallowed the diamonds … so everytime I swallowed them, I had to find them again.” She adds: “(In the latrine) I never sat on the hole, because I had to find my diamonds.” Said she would rinse them off “in the mud, or […] in the soup that we were gonna get.” (Unbelievable! That would be a serious crime for which she could truly be shot.) One day she was caught defecating in the corner and had to swallow the diamonds without “rinsing them off.” This filthy stuff is not repeated in the book.

When did she decide the diamonds were important to her story?

(Radio Interview) In 1997, according to Zisblatt, she got a call from the Shoah Foundation about being in a film. The woman said, “You’re talking in your testimony about diamonds, but not telling us where they are … where are they?” Zisblatt answered, They’re here. “Can we come see them?” they ask. Zisblatt says, Absolutely. So they came with a crew of 18 people to film her for The Last Days.

Remarks: In her ’95 taped Shoah testimony, she tells of getting diamonds from her mother, but after swallowing them the first time, never mentions them again. I don’t know why the film producers picked up on the diamond angle from her testimony; she doesn’t show a pendant with diamonds during her filmed testimony. But in the filming for The Last Days in 1997, she speaks at some length about the diamonds and shows a pendant with four gems, saying these were her mother’s diamonds she had saved by swallowing and defecating them out again and again.

Suicide-at-the-fence punishment changes from 5 to 100

(ST) Claims the SS threatened to torture to death 5 prisoners for every one who committed suicide by touching the electric fence. “Many people did go to the barbed wire … every time a transport came through, the barbed wires were electrified. When it was on, people would walk up to it just to die. […] so they (SS) said: For every person that’s going to take their lives, they’re gonna torture to death 5 of us. Of course, everybody ignored the barbed wire after that.”

(LD) Now she says the SS killed 100 inmates “in front of everybody” for each prisoner who electrocuted themselves at the fence. “When the electricity came on they ran up to it to electrocute themselves.”

(FD) She left this patently false story out of her book.

Tattooed right away or later?

(ST) She does not say she was tattooed on arrival, nor does she ever give her number. Later, when telling of the tattoo removal “experiment” she gives this bizarre explanation (@1hr31min): “I wasn’t tattooed right away. I was tattooed after they selected me for something. The reason we wasn’t tattooed right away is they didn’t want us to live. We were in that camp as reserves for the gas chamber, for the crematorium, because they were burning two men and one woman, because that was the best, efficient thing to have the crematorium work efficiently—because the woman has a little more flesh on her body because of her breasts, and the men don’t, so they were using two men and one woman for the crematorium. So we were reserve, is what we were told—every time we asked for some food or some ration [we were told], ‘You think you’re here to live? You’re here to be a reserve for that chimney!’ That’s when we found out what that chimney was.”

(FD) She receives a tattoo on her arm - number 6139716 - along with everyone else upon arrival, while she’s still holding the diamonds in her hand. (p. 35)

(LD) Another woman survivor testifies they were given a tattoo upon arrival.

When did she learn her family had been gassed?

(ST) “We didn’t find out for a couple of days.” (@1hr22min)

(FD) On the first night, she tries to sneak out of the barracks to find her mother. The woman in charge of the barracks stopped her at the door and pointed to smoke coming out of a chimney and yelled at her, “Your mother is just about now coming out of one of those chimneys.” Later that night: “I realized [it] was true. My mother was dead.”

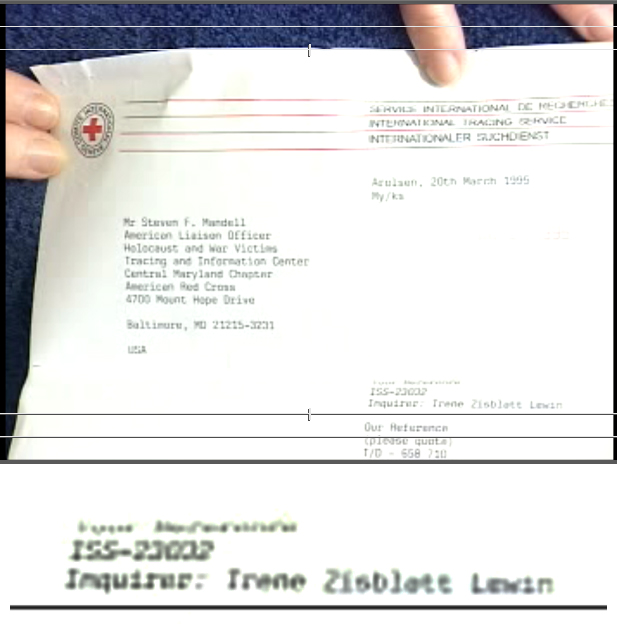

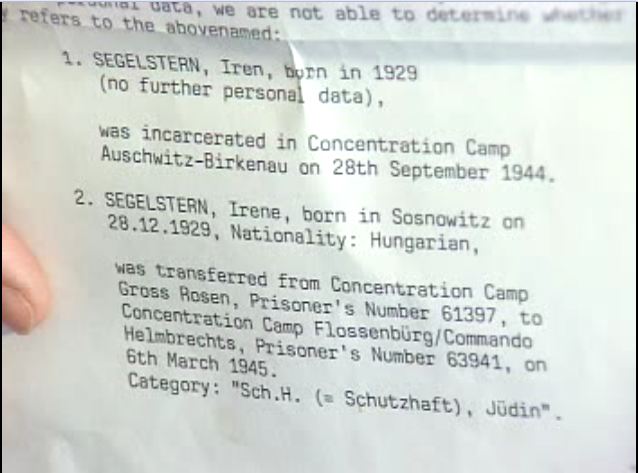

Above: Reply to a letter written by Irene Zisblatt Lewin to the Red Cross Tracing Service in 1995 inquiring about the records for Irene Seigelstein. More proof that she was listed with some agencies as Irene Lewin. (credit: Eric Hunt)

With her cousins or all alone?

(ST) She shared the bunk in her first barracks with two of her father’s cousins – one of whom was around her mother’s age, 33. These cousins were not mentioned previous to this, but suddenly they are with her. This is strange because back in Munkacs she said they were expecting her father’s cousins, but they never showed up; they learned one had been murdered with his whole family, including two daughters.

(FD) She’s in her first barracks alone, no relatives ever. But of the other 9 women who shared her bunk(!), one worked in the kitchen and whispered that the SS were putting chemicals into the soup to destroy their reproductive organs. This rumor is the SOURCE of her claim that the “evil Nazis” tried to destroy her reproductive ability. Later in America, she had two children, yet she still tells school kids that she was given chemicals for this purpose.

Mengele no – Mengele yes

(ST) After a month in camp, she was selected for experiments by a “German doctor.” The whole barracks of 1000 had to undress outside and 15 women were chosen for their “smooth, unblemished skin.” When asked by the interviewer if she knew the name of the doctor, she said No. “It could have been Eichmann (not a doctor), it could have been Mengeler (sic), you know after a while they all looked the same. It wasn’t important to us what their names were. […] I for one was not interested what their names were.” (@1hr33min)

(FD) At her first morning roll call, she was selected for experiments. Two men approached them; she heard the Kapo speak their names: Mengele and Toub. (p.43) She swallowed her diamonds again. Mengele, the doctor, selected her and 99 other women to line up between two barracks and remove their clothing. She was in the final group of 15 that was selected, sent to the showers, given clean clothes, and put on a train to Majdanek.

(LD) Dr. Mengele is never mentioned in the entire film.

Remarks: It’s noteworthy that Zisblatt only mentions Dr. Mengele twice in her Shoah testimony, and both times with uncertainty, and with some prompting. But in her later book (and also in her talks), Mengele, along with the diamonds, becomes a major theme.

Eye-color experiment differs

(ST) The 15 who were selected walked to Auschwitz where drops were put into their eyes and they were led into a dungeon underneath a barracks, where each was put in a small cubicle. They stood in water up to their ankles in pitch darkness for an unknown period of time. “THEY TATTOOED US THEN! When they selected us, they took us to this little section and gave us our number; they tattooed us. And then we went into the dungeon. So we had the arm, we didn’t know why we were tattooed, we didn’t eat, we just drank that water.” Some were blinded by this experiment, but all 15 returned to their barracks; later they found out the experiment was supposed to change the color of their eyes … but it failed. (@1hr37min)

(FD) After they returned from Majdanek, Dr. Mengele selected 5 from the 15 to go to the Birkenau Infirmary where “he put painful chemical injections into our eyes.” This time they stood all together in one prison cell in water up to their ankles. Their eyes burned. One of the girls finally spoke to her – it was “Sabka,” who was to become her faithful friend. “For the next four days we remained (there).” After being let out, Dr. Mengele examined their eyes and “seemed disappointed.” The other three girls were blind, and were immediately taken to the gas chamber, crying “Shima Israel.” Chana and “Sabka’s” eye-color was unchanged. (P. 46-48)

(LD) Only describes the eye-color experiment, but combines the 5 girls (FD) with the eye drops (ST). This time they were “tightly packed” in the dungeon. Afterward, “some of the people” (of five?) couldn’t see “for several days after that.” No Dr. Mengele – no “Sabka” – no permanent blinding – no one sent to the gas chamber. (@ 32 min)

Virus testing with and without Mengele

(ST) Next experiment was injecting a virus-containing serum under their fingernail. Only 5 of the original 15 were selected for this. That evening, she had a red-line going up her arm so she tore off a string from her clothing, tied it as a tourniquet on her arm and in the middle of the night went to the back door of the barracks, put her arm through the door crack and laid with her arm in the cool mud all night. In the morning, the line was down and they were examined again. She says that if the red line had still been there she would have been sent to the gas chamber.

(FD) Only she and “Sabka” are sent to the Infirmary for the under-the-fingernail injection. Dr. Mengele is there to do the torture. They are returned to their barracks for 3 days, then come back to the Infirmary for a blood test. Mengele comes in with sadistic hatred in his eyes and sticks the needle under her fingernail again. She writes: “Yes, that kind of hatred existed in the Twentieth Century in Nazi Germany.” That night she has the red-line reaction, but she sneaks all the way outside the barracks and lays outdoors all night with her hand buried in the mud. In the morning she is alright.

She dreams up an unbelievable punishment for the next day, given to her for trying to help “Sabka,” who was sick from the injection. She is made to stand very close to the electric fence, holding a brick in each hand with both arms straight out in front of her. If she moves even an inch, she will be electrocuted. She manages to do this for 12 hours after having a blood infection the night before!! Naturally, while she’s standing there all that time, she sees many evils taking place in the camp. This craziness is only in the book.

The injections continued every three days for the next two weeks, but with no more ill effects.

How she met Sabka

(ST) She first mentions “Sabka” during the 2nd experiment—the under-fingernail injection: “This one girl, her name was Sabka and she was Polish.” (@1hr42min30sec) She then describes how Sabka came to Auschwitz in 1943, saying “she was 19 years old when we met.”

Remark: “Chana” was still 13, awfully young to be the confidant of a 19 year old. This gives credence to the idea that Zisblatt was two years older than she says she was. Even though “Sabka” is a fictional person, Zisblatt is comfortable talking of her friendship with a 19 year old.

(FD) On the trip back from Majdanek, a beautiful girl sat next to her, the strong suggestion being this was “Sabka”(p. 46). Upon their return, she and the girl spoke to each other and exchanged names while standing in the watery dungeon during the eye-color “experiment.”

Sabka’s nationality changes

(ST) “Sabka” was Polish.

(FD) “Sabka” was Lithuanian (p.7). Zisblatt invents an elaborate story about 16 year old Sabka’s parents death in a mass grave, S’s escape from the grave and finding a cave to live in for two years.

How they escaped being made into lampshades

(ST) Five women, including Zisblatt, were taken to Majdanek, where the rumor was that Ilse Koch17 was coming to select prisoners with “smooth skin” for her lampshades (@1hr46min). Koch didn’t show up at Majdanek, so the five women were sent back to Auschwitz the next day.

Remark: The charge that Koch made lampshades and gloves from the skin of prisoners has long been debunked, but Zisblatt does her best to keep it alive in schoolkid’s gullible minds. She also thought Koch was coming from Innsbruck; didn’t know she was from Buchenwald. To make matters even worse for Zisblatt’s credibility, Ilse Koch was put on trial in a German Court in December 1943 on embezzlement charges for which she was found not guilty and never returned to any concentration camp after that.

(FD) The trip of fifteen to Majdanek is the first “experiment” she mentions in her book. She describes the bunk she spent the night in with 9 other women as filled with blood and feces. This, after being specially showered and given clean clothes before they left Birkenau! After 48 hours of supposedly waiting around for Ilse Koch, who never arrived, they were returned to Birkenau. (p.44-45)

Tattoo removal with and without Dr. Mengele

(ST) She and friend “Sabka” are now the only two left of the five; are taken to the “revere” to have their tattoo removed, but can’t remember if it was in Birkenau or Auschwitz. She describes it thus: Doctors strapped them onto a rusty table, injected things into their arms; then they were pulling, then cutting, without anesthesia, and within a week to 10 days (!) they found a way to get rid of the number. The nurse told them the reason for the tattoo removal: The SS were tattooed under their arm with the same kind of ink and now wanted to hide their identity, so the doctors are experimenting to find a way to remove their tattoos.

(FD) She, “Sabka” and twenty other women are marched to Auschwitz to the hospital there. She describes what she saw along the way. Dr. Mengele has 6 young SS in training, showing them glass jars containing deformed body parts of Jews. Then, coming over to the two girls strapped on the tables, he looks at her number 6139716 and says to his interns: “I must find a way to remove the tattoos from the SS … we will use the prisoners to test different methods for the deletion of their numbers.” She proceeds to write a lot about Dr. Mengele’s evilness, then describes the same removal process as above.

Remarks: This supposedly explains why Zisblatt doesn’t have an Auschwitz tattoo even though she was allegedly there. When asked by audiences where her tattoo had been, she points under her left upper arm18. But numbers were tattooed on the top left forearm, where they could be easily seen and checked.

Went to gas chamber with gypsy families, or 1500 women?

(ST) “They selected me with the gypsies.” (@2hr11min) “I think it was in December, because it was cold, snow … and the gypsy camp was not too far from the C lager; it was a family camp. I was just taken out of my (roll call) all by myself.” Then, as if she suddenly remembered19, she says, “I think that it was Mengele that took me outta there.” (This is first mention of Mengele since saying she didn’t know if he was the doctor who selected her for her first experiment.) She was put on a truck transport of Gypsy families on their way to the “gas chamber.”

Remarks: The last “gassing” at Birkenau, according to the official narrative, took place on October 30, 1944. But Zisblatt has no idea of this when she recalls it being in December. This may be the strongest “evidence” of fraud in her narrative. Surely one wouldn’t forget the exact time one was sent to die in a “gas chamber.” If she decided on December, so that she could claim the longest time possible at Birkenau—May to December (7 months max, although she claims 8 months)—she has fallen into a trap. May to October would be only 5 months.

(FD) “Suddenly,” at mid-morning, she was selected with 1500 other women to leave the camp (p. 74). Mengele is not present. The women were ordered to remove their clothes and marched naked until they were forced into a narrow passageway. At this point she realizes she’s in the #3 gas chamber.

(LD) Nothing about her gas chamber experience is brought up in the film.

How she escaped the gas chamber

ST) “As everybody (Gypsy families) was being pushed into the gas chamber” -after removing their clothing- “I was goin’ backwards and I got stuck in the door.” She hung on to the edge of the metal door and the big strong SS man couldn’t manage to push this starving child in, so he threw her out! She ran away and hid under the “eave” of the crematorium.

(FD) Basically the same unbelievable story with the 1500 women, only this time she “dug her fingernails” into the doorframe and wouldn’t let go. (With her inadequate diet and deprivation, could she have such strong fingernails?) When the big SS guard “threw her out onto the ramp” (there is no ramp) and walked away (!) she ran up the non-existent ramp and climbed under the roof.

Remarks: Being unfamiliar with the crematoriums apart from the rubble she first visited in 1994, Zisblatt doesn’t know that there was no place “under the roof” to hide and there were no eaves.

The Sonderkommando—friend or stranger?

(ST) Very shortly, a boy wearing a Jewish star came along to clear out the dead bodies from the chamber, saw her under the eave, gave her his jacket and said, “When I’m finished, I will be back. I know who you are.” She then tells a long story about how they met before in the camp and she had done him a favor which he was now going to repay. (@2hr18min)

(FD) The sonderkommando boy sees her, gives her his jacket and speaks to her in Hungarian. They have never seen each other before.

Sonderkommando has 3 months or 3 days to live?

ST) “Within five minutes he was back. It doesn’t take long for a crew to exterminate God knows how many hundreds of gypsies and bodies, you know?” He told her, “As soon as they turn off the electricity in the wires, there is a train going to a labor camp. If I find an open cart, I will throw you over the wires into the cart.” Zisblatt says he risked his life because, “He had 3 months more to live, if that.” Immediately, he rolled her in a blanket he had brought, threw her over the high wire fence, and she landed in an open wagon with other women in it.

Remark: The fences were almost 10 ft. high and the side track around Crematorium #3 was at least 100 ft. away—not close enough for this to be at all possible.

(FD) He said, “I’m going to throw you on a train that is waiting on the tracks. There are open cars on the train […] women going to a work camp.” Immediately, he tossed her (no blanket) and she landed in an open cattle car with other women (none ever spoke to her!). She had asked his name; he said it didn’t matter, he had only 3 more days to live.

Remark: The Germans did not transport women in open train cars in freezing cold weather, if ever, and even more so if they were valuable labor.

Train took her to Gross Rosen in former Czechoslovakia or Neuengamme, Germany?

(ST) The train car carried female “machine mechanics” to a small labor camp with one factory. She couldn’t remember the name of the town or camp (how could she forget?), but said it was in Sudeten Deutschland (former Czechoslovakia).

Remarks: This could be a sub-camp of Gross Rosen, which was located directly on a rail line not that far from Auschwitz. About 10 of the subcamps were for women and were reportedly at peak activity in 1944. It’s not believable that she couldn’t “remember” the name of the place—it’s more likely she doesn’t want to bring attention to it because she is telling a different story than the one she actually lived.20

(FD) The train took her to Neuengamme concentration camp in the city of Hamburg in Northeastern Germany (p. 77)—many days travel from Auschwitz. (In an open cattle car, wearing only a jacket?) On page 79, she writes she “wasn’t sure of the exact dates” though by 2008 she had plenty of time to figure it out.

Remarks: It’s reported that some women prisoners from Auschwitz were transferred to the sub-camps of Neuengamme in the summer of 1944, not in October or December.

(LD) Nothing about leaving Auschwitz is brought up.

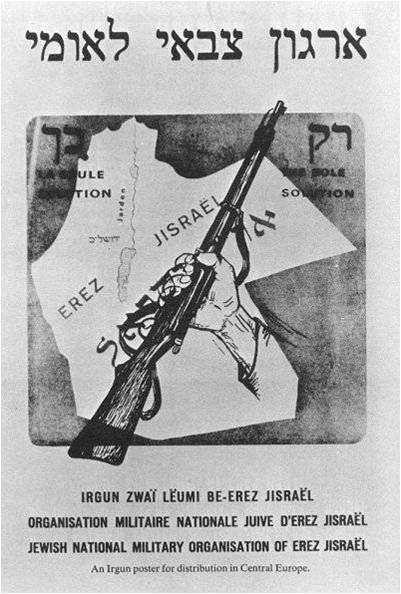

(Above) Map showing Neuengamme far up in northwest Germany. Gross Rosen is closer to Auschwitz, with Flossenbuerg west of G.R., and Pilsen directly east of Flbg. It makes no sense for Zisblatt to say she was in Neuengamme, so why does she? (credit: Eric Hunt)

Her job was to repair machines or pack ammunition?

(ST) Unbelievably, she re-discovered “Sabka,” who had been sent away after their tattoo-removal, in the bunk below hers in the morning. Her job in this camp was to repair machines that Czech men operated. Of course, she didn’t know how, but she tells an elaborate story about the Czech machine operator who helped her out.

(FD) Again, she finds “Sabka” in the bunk below hers, but here they both have the job of packing ammunition for the front lines. No Czechs in this camp.

Different routes for the “Death March”

(ST) The first week in January, the “couple of hundred” camp inmates were ordered on a march. (@2hr36min) Prisoners from outside came into their camp and 5000 were assembled. They wore their normal shoes and clothing, and were given a blanket. Zisblatt claims they walked from January until April with only snow to eat. When asked if she remembered the route: “I remember passing Breslau and Dresden […] I remember the signs as we were going.” Then, “The factory was deep, deep Germany … Dresden was below where we were, so … we didn’t pay attention where we were going cause we didn’t have no choice anyway. But by April we were somewhere in the Pilsen area and we knew we were close to Czechoslovakia.”

Remarks: They were in Czechoslovakia when they left! If Dresden was below the factory/camp, it was not in Sudetenland as she said it was. She has poor understanding of geography or she is just making it up as she goes along.

(FD) In January, the 5000 prisoners of Neuengamme (in Northern Germany) were assembled, each given a thin blanket, a pair of wooden shoes, an “article of clothing” and told to march. (p 79) They marched in the snow, which was their only food, tearing strips from their blanket to wrap their feet. Many died along the way; by April only a few hundred marchers were left. We are not told of any landmarks or towns to indicate where they were.

Remarks: The only march from Neuengamme was northwards to the Baltic Sea in the last weeks of the war, according to USHMM website21.

(LD) All she said was, “The Nazis didn’t want anyone to get liberated, so they were herding the people away from the camp.”

Remarks: She fancies herself an expert on Nazis, as well as on Dr. Mengele.

Liberation: with or without General Patton?

(ST) In April, Allied planes shot at their convoy; in the confusion the two girls managed to drop out of the march. They walked about “all night long,” and fell asleep next to a stream. In the morning, they were awakened by an American soldier wearing a Jewish mezuzah around his neck. She heard “loud rumblings, noise, cars and footsteps—the whole Army was here! They came and found the two of us and they had an interpreter, so we communicated. This was General Patton’s Third Army that came through there […] This one guy was always screamin’ and that was General Patton, he was screamin’ and yelling, and then the Red Cross truck came down and they put us in the truck.”

Remarks: Part of Patton’s army was in that area then, but not Patton himself.

(FD) They dropped out of the marching column after a bombing raid and wandered “for several more days,” sleeping at night under their now half-blanket. “One morning,” two soldiers, one wearing the mezuzah, wake them. Other soldiers came and spent all day talking with them, cooking for them, holding her in their arms, and one was able to speak with her in German. They were taken to the soldier’s camp and put into a Red Cross truck, with beds, for the night. But no mention of General Patton screamin’ and yelling this time.

(LD) “Planes came out from behind the mountains and bombed our convoy; none of us were hurt. That’s when I found out the first time the US was at war.”

Bread or crackers?

(ST) When asked what they wanted to eat, she only wanted a whole loaf of bread all to herself, so they gave her a loaf of bread.

(FD) They had no bread to give her, only crackers in little cardboard boxes.

Remarks: Zisblatt obviously learned that soldiers have rations; they don’t carry around loaves of bread. In addition to this, she claims they cooked scrambled eggs for “Sabka.”

April or May?

(ST) In the morning, “they (soldiers) wanted to know where we lived.” The girls said, “We would like to go to a hospital, maybe … somewheres where it’s safe. They decided the hospital was the best place to take us.” It was April 1945, white flags were out but still a lot of fighting going on.

(FD) She learned from her soldier-liberators the day before that it was May 7, 1945.

“Sabka’s” death and burial

(ST) Even though Zisblatt just said what she did above, she then said, “When we got up in the morning, my friend “Sabka” was dead. She died in her sleep.” They bury her in the woods wrapped in her old blanket because “Chana” didn’t want “Sabka’s” body to be autopsied at the hospital.

Remarks: The interviewer didn’t question Zisblatt on how Sabka could be talking in the morning and then have died in her sleep. Zisblatt had remembered that an imaginary person cannot be registered in a hospital.

(FD) In the morning, the soldiers bring them breakfast, but she can’t wake “Sabka”; a medic finally tells her she is dead. The medic, the Jewish soldier Bob and another soldier spend the entire morning consoling her, then spend the rest of the day digging the grave. They tell her they would come back with her after the war to give “Sabka” a “proper burial.”

Hospitalized in Pilsen or Volary?

(ST) She made the statement @2hr54m40s, “They took us into the hospital at Pilsen.” At 3hr1m40s, she said she was in an American Army hospital in the Pilsen area that was formerly a German hospital. “From the hospital, at the end of that summer […] they took us to Salzburg, Austria to a Displaced Persons camp. And this was close to 1946.”

Remarks: According to the World Jewish Congress, Irene Siegelstein, age 16, born in Poleno, Hungary, father’s name Moshe, was on the list of Jewish girls now at the civilian hospital in Volary, Cz, on April 25, 1946.22 This would mean Zisblatt was in the hospital for an entire year, which is not credible, and contradicts what she herself says. Yet the list exists, so when did she actually enter the hospital?

(FD) She was taken to an American Army hospital in the “Pilsen area” where “all the other residents were young military men.” (p. 98) She is treated for typhus and malnutrition. “One day” a general, who she later learned was George Patton himself, came to the hospital and made “a special visit to my bedside.” He asked her questions through an interpreter, then pulled four buttons from his sleeve and took the purple scarf from around his neck and gave them to her. Yet she has never produced these gifts as she does the diamonds, which can’t be traced to any particular person or time. She “spent two months in the hospital in Pilsen.”

Remarks: In her ST, she sees Patton in the field; now in FD she just sees him in the hospital—she is determined to have him in her story. Zisblatt refuses to say the word Volary, yet everything indicates that’s where she was. Pilsen is approximately 40 miles from Volary. Many of the evacuated female camp inmates from Poland who were set out on foot marches in January ended up in Volary, very possibly because there was a German hospital there.23

Displaced Persons camp

(ST) She only says “They took us to Salzburg, Austria … I was with people from Poland, from different countries, waiting for borders to open up, waiting for papers to come through to go to different countries. Most of the people were hoping to go to Palestine, but that was closed too.” (@3hr3min) She says (Jews) had to be smuggled in and “we tried that also, we did get to Italy and laid on the beaches for 5 days and nights waiting for a ship to come get us … but there was no ship.”24 When asked by the interviewer—“Who did you go with?”—she remained vague by answering, “Just, uh, kids that, uh, well, there were a couple of leaders that were very devoted, uh, Haganah25 people and Zionists … they came one night” and recruited the residents to try to get to Palestine illegally. She says, “Most of the people, we didn’t even know each other.” She stayed in the DP camp until 1947. She had information placed in newspapers in the States and an uncle in the Bronx answered her “article” in The Forward.26

Remarks: When she says ‘us’ followed by ‘people from Poland’, it indicates she was with mostly Polish people. I suspect Zisblatt changed “Sabka’s” identity from Polish to Lithuanian because, as time went on, she wanted to distance herself from every Polish association, not least because she is hiding her early marriage to the Pole Alter Lewin, along with other Polish ties she may also be hiding. I note her failure to put names to any of the “we’s” and “us’s” she is so fond of using. She spent two years in the DP camp, was never alone, and not one friend or helper is mentioned by name. Two years versus one year in German camps—the one year is filled with events and experiences worthy of an entire book, but the two (in spite of her marriage) are devoid of anything worth talking about.

(FD) When she was “strong enough to leave” the hospital she was assigned a guardian to help her get situated in the DP camp. Although she says he became a friend to her, he is not named. According to her statements in FD, she would have arrived in the DP camp in early July 1945—not, as she tells in her ST, “at the end of summer … close to 1946. Otherwise, she tells essentially the same story but adds a period of time living with other Jewish refugees in the home of an elderly Salzburg widow, who she takes great pains to describe as a hateful German "Nazi" whose husband had been in the Gestapo!27 We’re only given the poor woman’s first name—Herta (p. 101-2)

She writes: “Staying in this camp I made new friends,” but she doesn’t give a single name or describe a single friend, including any mention of Alter Lewin.

(LD) None of these experiences are in the Spielberg film.

Voyage to America

(ST) On November 8th, “I arrived on the Marine Flecher (sounds like) in New York and met my family that I never knew before.” (@3hr5min) She says nothing more about the trip or about her new family and gives only a sketchy outline of her early time in the US: she went to school at night, taking high school equivalency in English, and worked during the day in a bakery. When she finished school, she went to work for RCA as what sounds like an assembly line worker. She was active in B’nai Brith and president of BBYO (its youth organization), and an enthusiastic seller of Israeli war bonds.

(FD) In October 1947, she received her official papers to travel to the US on the ship “Marine Fletcher.” Now she tells us how “Chana” became “Irene” when an immigration official handed her a passport with the name Irene Seigelstein. (p. 103) “‘I panicked … this is not my name … I have never heard of that name,’ I cried. ‘From this day forward, you are Irene,’ he replied. ‘That is a nice name. That is an American name.’ I was ecstatic. I was so honored to have an American name.’”

Remarks: From this we can fairly conclude that “Chana” is a fictional representation of “Irene,” and that when she left Europe for America, the fiction ended and reality began. Or did it?

She writes little of the voyage, saying only the ocean was rough and she was seasick. Though she was 10 days on the ship, a brand new type of experience, she doesn’t mention a single person she met or a single event that took place. Her uncle Nathan met her at the dock and drove her to New Jersey to meet the rest of the family (p. 104). On page 111, she says, “I became a member of B’nai Brith Women. As chairman of the Israeli Bond Drive, I organized all the events to try to sell bonds. I really think that was my way of starting to give of myself.” Give of herself—very particularly to Jews only, and so it continued throughout the rest of Irene’s story, even until today.

Remarks: Here again, did Zisblatt ditch her first husband, Alter Lewin, as soon as she landed, or was she not really met by “Uncle Nathan” at the dock and taken to meet the rest of her family?

Concluding Remarks

There is much more in her book and on the videotape that is unbelievable and insults the reader’s/viewer’s intelligence which I have not even touched on for the reason that she is reasonably consistent in her telling. But what can we conclude about all the major and minor differences between Irene Zisblatt’s archived Shoah Testimony and her later autobiography?

The first thing that comes to mind is that between 1995 and 2008, she thought of a way of telling her story that she liked better. She realized that some things she had said in 1995 didn’t make sense or they didn’t align with what other survivors said, so she corrected or changed these things. She also took the opportunity to add even more drama and “Nazi sadism” to her incarceration (for example, Dr. Mengele as the doctor who used her for experiments; her punishment holding the bricks for 12 hours as she observed new Hungarian and Ukrainian arrivals being abused; and, of course, swallowing and retrieving the diamonds from her feces over and over) to increase the suffering she experienced firsthand, while she also toned down some others. She put herself in the center of just about everything she had ever read of the Holocaust! All in all, this makes The Fifth Diamond a calculated exercise in pushing an anti-German agenda rather than a truthful record of her experience.

Was Zisblatt ever really at Birkenau? I believe it’s possible she wasn’t because her account of it is so filled with inaccuracies, yet I’m willing to accept that she was. Another question is: if she was, for how long? A Red Cross Tracing Service document made available by her shows an Irene Segelstern was incarcerated on 28 Sept 1944, which could possibly be a contradiction of her story that she arrived during the mass deportation of Hungarian Jews in the spring of that year. Zisblatt’s own dating in her narrative(s) would actually have her at Birkenau around April 20; yet according to several sources, the very first two trainloads left on April 29th and 30th, both arriving at Birkenau on May 2nd, carrying a total of 3800 Hungarian Jews.28 The Jews from Munkacs were not on these trains, meaning they arrived after May 2nd.

The fact that the birth date and nationality matches Zisblatt’s indicates the misspelling of the name is probably a mistake, UNLESS Irene Zisblatt is not and never was Irene Seiglestein and is a total fraud. It is possible.29 Her birth year is given as 1928 or 1929 on all holocaust-related listings—never 1930.

Above: A Red Cross document is held up to the camera by Irene Zisblatt. She received it in response to her inquiry, sent as Irene Zisblatt Lewin, about Irene Seigelstein (notice it reads “Segelstern). Ironically, it lists her at places after A-B different from where she says she was. Schutzhaft means protective custody. This document creates more questions than it answers. (credit: Eric Hunt)

Identity confusion

I have doubts about her identity, since she traveled to the US as a married 18-year-old named Lewin, and used the name again to inquire into Irene Seigelstein’s holocaust records. I have doubts about her family and their supposed perishing in “gas chamber #2.” The only confirmation that her mother and father, Rakhel and Moshe Zeigelshtein of Polena, died at Auschwitz is a registration form made out by Tzipora Erbs, a niece of Moshe, in 1957 to Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum database—where anyone can submit a name. The Yad Vashem database is not proof of anything. Additionally, Zisblatt’s four brothers and sister do not come up on that database and you would think the relative who registered the parents would have also registered them. There are no official records of the Zeigelshtein/Seigelstein family deaths at Auschwitz that I have been able to find. But how does one go about proving that someone was murdered at Auschwitz? One doesn’t; there is no proof.30

There are several records for Irene Seigelstein (with slightly different spellings), but they don’t match the story she tells in The Fifth Diamond or in her talks on the lecture circuit. She says flat out, “I survived Auschwitz, Birkenau, Majdanek and Neuengamme, and a death march.”31 Yet her records say she was an inmate at A-B, Gross Rosen and Flossenbuerg/Helmbrechts (which she entered on March 6), and was liberated from a civilian hospital in Volary, Cz., not alone in a forest and then taken to a hospital. Why does she refuse to mention Gross Rosen and Flossenbuerg 32 in her ST, her book and her talks? Is it because she could not then say she was on a 3-month death march? From Birkenau she went to another camp (she says in December, but probably in October), and by the first week of January she embarked on a death march. While it is possible that she was on a couple of shorter marches between the above mentioned camps, it’s just as possible she was not. Since her account is untruthful from start to finish, there is no reason to believe her about a “death march.” I think she read about them and decided to put it in her own story, as she did with so many things. Her death-march account sounds amazingly similar to this one by Szewa Szeps.33 As to “surviving Majdanek,” the only time she spent there was either 24 or 48 hours waiting for Ilse Koch to show up—another piece of fiction.

Another, perhaps more persuasive reason for Zisblatt to misrepresent the camps she was in is because they were not “death camps.” She may be hiding the true reason she never got a tattoo: that she was “in transit” at Birkenau and was soon sent to another camp to work. Especially if she were really 14 or 15 years old, rather than 13, she would have been useful labor—not wasted carrying rocks back and forth in Birkenau for no purpose other than sadistic, or for “experiments.” A-B was the only camp where inmates were tattooed; her lack of a tattoo is therefore a problem for which she invents her cover-up story of tattoo removal. Recall that the tattoo number she gives herself does not fit the numbers that were used at A-B in 1944; that number was her prisoner number at Gross Rosen.

Spielberg’s documentary and Shoa Library undermined

Does she think no one will notice all these glaring discrepancies in her narrative? Up until Eric Hunt took a look at it, no one did! That’s how it can be that holocaust fictions are passed off as fact—people won’t use their critical faculties when they listen to “holocaust survivors.” One reason for Zisblatt’s complacency is probably her close association with Steven Spielberg, an “untouchable” figure among contemporary global elites. As one of the “stars” of his award winning documentary, she can understandably feel protected under his broad wings. But if her holocaust narrative is widely exposed as a work of fiction, this can also expose Spielberg as a perpetrator of fictions, and seriously undermine the entire credibility of The Last Days—the cover and advertising of which states: “Everything you are about to see is true.” If put in legal terms, it may be that what you “see” filmed is true-to-life, even though the relationships, context, and the words that are put with what is shown visually, are not. This is the way clever lawyers help the rich and famous to lie without really lying.

Not only is The Last Days undermined, but the entire Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation Library, under Spielberg’s executive directorship and now housed at the University of Southern California (USC), becomes suspect. The original interview of Zisblatt conducted by Jennifer Resnick in 1995 is one of those “soft-ball” sessions in which contradictory and otherwise incredible statements are not questioned. There are many red-flags thrown up by what Zisblatt says, and at times Resnick has a hint of surprise in her voice, but all is accepted at face-value. It may even be proper for the interviewer not to interject or interfere, but the producers/directors of The Last Days had a responsibility to be sure that their witness’s testimony panned out. Instead, it seems they were more interested in a memorable angle—such as swallowing and retrieving the diamonds—and a personality that was willing to indulge in untruths with a convincing, sympathetic manner. Considering what I have revealed in this article, the producers/directors of The Last Days are guilty of failing to do even the minimum due diligence, and of manipulating the public’s beliefs and feelings to fit an agenda—just as I said that Zisblatt had done in her autobiography—rather than giving a truthful rendering of what really took place during “those days.” The musical sound track and film clips that are interspersed with the speaker’s words are clearly there to create emotional reactions that will overpower critical thinking.

Inspiration for the diamond story

In light of the above, some further reflections on Zisblatt’s diamonds are in order. On the last page of her book (p. 167), there is a photograph of the teardrop pendant with the four diamonds. Someone pointed out to me that they appear to be two matched sets, with two larger and two smaller diamonds—suggesting they may have come from two pairs of diamond earrings that Zisblatt may have owned. In The Last Days she shows the pendant, but keeps turning it in her hand so that the diamonds cannot be seen clearly while she says, “See, they are all different sizes and shapes.” From what I see, this is not so; they are surprisingly regular.

Considering the timing, it’s fair to ask: Did someone from The Last Days come up with the idea of featuring the diamond-saving, diamond-swallowing story? This is where the full-blown diamond story, and the pendant, first appeared. In the Radio Interview, Zisblatt said they asked about the diamonds that she spoke of in her testimony, but in her testimony she only said she swallowed them when she arrived at Auschwitz. So where did they get the idea, from what she said in her testimony, that she still had them? I go over this again because I think it is a key to some important discoveries that I may develop in a future article.

I’d like to close with a few comments on Zisblatt’s personality as I have come to see it. One character trait that stands out to me is her strong desire to be the center of attention. This crops up in several places. One is in making herself a favorite patient of Dr. Mengele, and even in being selected for “experiments” to begin with. As Dr. Mengele’s patient, she’s in a privileged position to know all about this famous, but shadowy character, and speaks about him as an expert (but she never describes what he actually looks like). Another is her insistence that she and her imaginary friend “Sabka” were liberated all by themselves in a forest by American soldiers who made a big fuss over them. Then “Sabka” disappeared and she was alone with the soldiers in the military hospital where she was the only female—she is not just another Jewish girl with all the other Jewish girls in the civilian hospital that was created for them. And while in the military hospital, none other than General George C. Patton himself came to her bedside and was so touched by her story that he pulled buttons off his uniform and took the scarf from around his neck to give to her!

As I asked at the beginning: What kind of a person can come up with such outrageous lies, and should such a person be given free access to influence America’s schoolchildren? This is an important question that every responsible individual reading this should ask, after which they should come up with an agenda of their own.

Endnotes:

1) In the same year Schindler’s List came out in 1994, the teaching of the Holocaust had become mandatory in Florida schools, so there was now a ready market for holocaust survivors. Zisblatt moved to Florida in 1990.

2) “I had no problem remembering just about everything on the 1st day.” Irene Zisblatt radio interview, Ithaca Press and Artists and Authors Publishers of New York Radio Hour, Artists First World Radio Network, www.artistfirst.com, Interviewer: Tony Kay

3) (RI) ibid

4) (RI) ibid

5) (RI) ibid. Zisblatt speaks of editing out of her manuscript things that were not appropriate for children and schools. She wanted her book to be used in schools for “educational” purposes.

6) The Jewish ADL (Anti-Defamation League) provides schools with extensive teaching material, including lesson plans for grades K-12 and for pre-school children age 3 to 5. They conduct teacher training seminars and give advice to teachers. Another major resource is Holland & Knight Charitable Foundation, a Jewish law firm that provides an online comprehensive teacher resource guide, as well as sponsoring a national essay contest on The Holocaust for high school students and free trips for teachers. The State Boards of Education defer to these and other Jewish “charities” to provide the Holocaust Studies curriculum.

7) Zisblatt speaks four or five times a week all over the U.S. and Europe. She figures she has spoken to about 400,000 people each year since 1994. (http://www.pressofatlanticcity.com/news/press/atlantic/article_3d3d2f34-a5ca-5437-b43c-964990ff018d.html)

8) ALIEN PASSENGER MANIFEST For Passengers Traveling to the United States under President’s Directive of Dec. 22, 1945 is the heading on the document. It carries the signature of the Immigrant Inspector. http://erichunt.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Irene-Lewin-9.jpg

9) Fanny Horowitz, her father Moshe Zeiglestein’s sister, married to Morris Horowitz.

10) Family members and funeral directors are very particular about names in obits. This is not likely to be an error. She obviously began at some point to call herself Stein, doubtless before she met and married Weisberg in 1956.

11) http://www.zoominfo.com/people/Zisblatt_Jack_1322909813.aspx

12) Interwar Munkacs was about 50% Jewish (like Poleno), filled with Hasidic Jews wearing their traditional garb. The first movie house was established by a Hasidic Jew; it and most stores closed on the Jewish Sabbath and Jewish holidays. The Jews of Munkacs were the first to be restricted to a ghetto.

13) Peter Kleinmann, a Munkacs Jewish resident of the time, wrote in “The Fallacy of Race and the Shoah,” University of Ottawa Press: “Just after Passover, on 18 April 1944, the kehilla announced with posters and proclamations by drummers that all Jews must move into the ghetto. Within a week, 13,000 Jews from Munkács and some 14,000 from surrounding areas were rounded up […] and held in the ghetto and those from the rural areas were held in the Sajovits brickyard.” That would put the Zeigelstein’s arrival considerably later than two days after Passover on April 10th.

14) Other survivors have recorded that it was a three day trip and the train stopped several times for water. Each train car had two buckets; one for water, one for bodily elimination. The men got out at each stop to clean the pails and get fresh water. See John Mandel at http://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/interview.php?D=mandel§ion=10 and Peter Kleinmann at http://www.cjvma.org/e/albums/kleinmann/039-042.html

15) Peter Kleinmann reported 50 to 60 people in each box car.

16) According to the Auschwitz Prisoners Data Base, the Auschwitz prisoner number "61397" belonged to Agnieszka Pastuszek, a non-Jewish Polish political prisoner who had arrived from Katowice prison in Sept. 1943. After February 2, 1942, Auschwitz prisoner numbers were never issued twice.

Also, according to the USHMM website, the sequences of numbers introduced in mid-May 1944 were prefaced by the letter A for women and B for men, and began with “1” and ended at “20,000” for men and “30,000” for women. Thus, Irene’s number doesn’t match the numbers given to Hungarian Jews. For a look at an authentic tattoo, go here: http://hopelutheranchurch.net/social.php

17) Ilse Koch, dubbed by the press as “the bitch of Buchenwald” was married to the commandant of Buchenwald, Karl Otto Koch. She had the misfortune of being the target of evil rumors, such as using the skin of Jewish prisoners to make lampshades. However, the story went that it was tattooed skin that Koch wanted, but Zisblatt doesn’t seem to know that; she says Koch was looking for “smooth, unblemished skin,” like her own. Ilse Koch was put through two show trials after the war, and eventually died in prison. You can read about her trials (4 pages with photos) here: http://www.scrapbookpages.com/DachauScrapbook/DachauTrials/IlseKoch.html

18) Here is a picture of Irene Zisblatt pointing to the spot where her tattoo was removed: http://www.scrapbookpages.com/AuschwitzScrapbook/History/Articles/IreneZisblatt.html

19) I think it’s very likely that her interviewer, Jennifer Resnick, encouraged her during one of the breaks to remember if she ever saw or had any interaction with Dr. Mengele. It was Resnick who asked her earlier if she knew who the doctor was during her first selection for experiments, and Zisblatt said no.

20) A Red Cross Tracing Service document that Zisblatt holds up during her videotaped Shoah testimony shows Irene Segelstern, born 12-28-1929, was transferred from concentration camp Gross Rosen, prisoner #61397, to concentration camp Flossenbeurg/Commando Helmbrechts, prisoner #63941, on 6 March 1945. This was when she was, according to her testimony, in the middle of a death march! The first number was, according to her, removed from her arm at Auschwitz, deleted from the records, and she got a new number and a new name. Yet this is the number she has at Gross Rosen, which does not necessarily correspond to a tattoo.

Helmbrechts was a women's subcamp of Flossenbuerg in Bavaria, founded in the summer of 1944. The document also says that Irene Segelstern was incarcerated at Auschwitz-Birkenau on Sept. 28, 1944—not April or May.

21) “…and from Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme northwards to the Baltic Sea in the last weeks of the war.” http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005162

22) http://resources.ushmm.org/vlpnamelistimages/WJCpics/randy/993.pdf

23) http://www.gjt.cz/includes/military/DMUS/dmus.htm

24) This sounds a lot like the equally vague trip to Majdanek to meet with Ilse Koch who never arrived.

25) Haganah was the underground Jewish militia in Palestine during British rule from 1929 to 1948 that became the national army of Israel after the partition of Palestine in 1948.

26) A well-known Jewish newspaper in the US.

27) Zisblatt, another girl, two married couples and two boys (8 in all) were “moved into the upstairs of a home owned by an old woman. (She) was forced to share her home with victims of the concentration camps […] for the first few days we didn’t even realize she was there.” They used the kitchen downstairs—I truly can just imagine what shape they left it in! “In the first week we were there, I played her piano, which was in the living room. She instructed me to never touch her piano again. […] Herta was not a gracious host.” After a couple months, the group decided to go back to the DP camp. Taking over the homes of Germans to house Jewish refugees was a common practice of the Allies for several years after the war.

28) "The Holocaust Chronicle," Louis Weber, Publications International Ltd, Lincolnwood, Illinois. Also, "Auschwitz, a New History," Laurence Rees, 2005.

29) The correct spelling for this common Jewish name is Siegelstein, the way Nathan Siegelstein of New York, who she claims is the uncle with whom she lived upon entry into the US, spelled it. Yet she has always spelled her name Seigelstein, which is a misspelling and would be pronounced Sigh-gel instead of Say-gel. Some records for the holocaust survivor Irene spell the name Segelstein, which is actually a more phonetic way of spelling Siegelstein. This gives some credence to the speculation that Zisblatt got the spelling wrong when she “took” the name/identity of this holocaust survivor. This would not be the first time it was done. Elie Wiesel, for example, has been accused by another Buchenwald survivor of stealing the identity of a real Buchenwald survivor who was this man’s friend. He has written a book about it.

30) There are official German records, released from Soviet custody, that show all deaths at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the nationality of the deceased and cause of death. The numbers are very low. The million that are claimed to have been killed/gassed at A-B are said to have not been registered, so there is no way to prove their deaths.

31) http://www.herald-dispatch.com/videos/x140292583/Video-Holocaust-survivor-Irene-Zisblatt and FD, p, 120.

32) The Helmbrechts camp population was mainly non-Jews, but in March 1945, a group of over 500 Jewish women arrived on foot from the Gruenberg subcamp (of Gross Rosen) in Poland. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helmbrechts_concentration_camp There is NO source for this information at wikipedia, not surprisingly, but the page goes on to state that in April the women of Helmbrechts were set out on a march to Dachau, but were turned toward Czechoslovakia instead. The march ended in a small farming village with an Allied air raid on the group on May 8, 1945. The US Army found them the next day.

Holocaust Scholar Finds “Diamond Girl” to Be a Work of Fiction

- 16471 reads

by Carolyn Yeager, January 2010

copyright Carolyn Yeager 2010

Joachim Neander, PhD, independent scholar from Cracow, Poland, examines Irene Weisberg Zisblatt’s holocaust survivor narrative and concludes it is “not in accordance with the historically established facts,” is “exaggerated,” “implausible” and not true overall. Neander has contributed to publications in Poland, Germany, Israel and the USA. In 2001-02 he had a Charles H. Revson Foundation Fellowship for Archival Research at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

His January 9th article Irene Zisblatt, the "Diamond Girl”- Fact or Fiction? can be read here: http://holocaustcontroversies.blogspot.com/2010/01/irene-zisblatt-diamond-girl-fact-or.html#more.

Dr. Neander asks in the title of his critical review of Irene Zisblatt’s autobiography The Fifth Diamond, which purports to be a Holocaust survivor ‘true story,’ or memoir, whether it is fact or fiction. He comes to the only conclusion possible for a man who wishes to maintain his reputation as a scholar—that it is mostly fiction.

However, probably for the reason that he seems to have been assigned this project by some well-known Holocaust defenders (Kenneth Waltzer, Chairman of the Jewish Studies Dept. at the University of Michigan, who provided him with the Seigelstein documents, for one), he has tried to soften the blow wherever he thinks he can, going out of his way to find some positive things to say about “Mrs. Zisblatt” and her narrative. These positives are mainly in the realm of having a forgiving spirit and a sympathetic attitude toward an “elderly lady” who has suffered in her life. But Neander rightly decides that truth must be upheld, it being more important that not hurting someone’s feelings.