Battle of the Architects, Part 2

Battle of the Architects, Part 2

The Contradictious Speer

From Hermann Giesler’s memoir Ein Anderer Hitler

Der zwiespältige Speer, pages 332-339

1977 edition, Druffel-Verlag

Translated by Wilhelm Kriessmann and Carolyn Yeager

copyright Carolyn Yeager 2014

This section from Giesler's memoir Ein Anderer Hitler deals with his correction of Albert Speer’s insulting statements about the Fuehrer at occasions when Giesler was present or knew differently because of his own experience with Hitler.

To add some perspective to Giesler’s account, we remind you that Speer’s biographer Gitta Sereny titled her book, Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth.

In addition, Nicolaus von Below, Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant from 1937-45, wrote in his memoir At Hitler’s Side about an incident of seeing a striking red color appear in the sky while in the company of Hitler on the terrace at Obersaltzberg in Aug. 1939. He told Hitler it augured a “bloody war.” He said he “recounted this conversation to Speer in 1967 but later he (Speer) attributed my remark erroneously to Hitler in his book Erinnerungen.”1

Similarly, Christa Schroeder, one of Hitler’s secretaries, when describing Hitler’s walks around Berchtesgaten and a particular rocky promontory with a guard rail that offered an outstanding view, wrote: “Speer is mistaken when he says that Hitler had no feeling for the beauty of the landscape. Hitler would always wait at this promontory for his guests to catch up and then all would enjoy the view together.”2

But these are nothing compared to what Hermann Giesler has to say. The following is found under the heading “Der zwiespältige Speer” in Giesler’s Ein Anderer Hitler. It begins with city visits the three of them made together for the purpose of furthering their architectural and city planning ideas.

* * *

When he wrote about Hitler’s views on architecture [in his first book Erinnerungen (Reminiscences)] , Speer preferred to use Adolf Hitler’s visits to the cities of Paris, Augsburg and Linz to degrade Hitler with malicious remarks and arbitrary insinuations without recognizing how much he degrades his own credibility thereby.

When describing Adolf Hitler’s trip through Paris with the two architects and the sculptor he regarded most highly (Speer, Giesler and Arno Breker), Speer uses incorrect data. Speer could not describe that city visit in a more hateful way than by his closing remark: “The final destination of our trip was the romantic, sweet imitation of early-medieval cupola churches, the Sacre Coeur church at the Montmartre, a surprising selection even for Hitler’s given taste.”

To put Sacre Coeur, which fits so well in the picturesque world of Utrillo,3 into Hitler’s architectural world is not only an insinuation but an intentional infamy. Because Speer knew very well that the last stop of our Paris trip was not Sacre Coeur, but the panoramic view from the Sacre Coeur of the city’s architectural layout.

The same resentment can be noticed when Speer gives his opinion about Hitler and the city renewal of Augsburg. He uses much space for it and takes a chance to include in his remarks the “intriguing” Martin Bormann and, further on, also me. There you can read: “Hitler found in Hermann Giesler an architect who conceived and precisely executed his intentions. The first design of the Augsburg forum, however, was too similar to the planned Weimar project, also by Giesler. When Hitler criticized it, Giesler put a baroque crown on top and Hitler became enthusiastic."

Indeed, that simple it was! My designs of the Augsburg forum never showed even the least similarity to the Weimar forum, although they did, at their first stage, not yet comply with Hitler’s idea of the Augsburgian city character which he wanted to be integrated into the new part of the city. After my first design, the Augsburg Tower was never changed. Speer writes further “That project was financed by postponing apartment buildings.” But it was not financed at all and never built.

WHO’S TO BE BURIED IN LINZ?

Speer’s description of the Linz city visit also needs explanation. Speer combines two visits of Adolf Hitler, September 1940 and spring 1943, into one. And he again talks it down and manipulates it. Is he not aware that he cannot recklessly spin his yarn? Did he stay to Hitler’s right side and I to his left or the other way around?4 Speer turns our visit to the Nibelungen bridge with the Siegfried and Kriemhild sculptures into a disgraceful tirade. Adolf Hitler had suggested to me that in judging those sculptures one should not see them as free sculptures but as decorative symbols of the bridge and its name. Maybe, he added, the base of the sculptures should not show a relief but a mosaic—to emphasize its decorative meaning.

Speer then started with the nonsense about Hitler’s gravesite. “High above the city at the upper tower level,” he pontificates in a quasi-pre-Raphaelian5 mood, and adds, "I think it was that afternoon when Hitler, carried away by his own enthusiasm, declared for the first time that his sarcophagus should be placed at the ‘future symbol of Linz,’ the highest tower of Austria." Adolf Hitler never said anything like that. From the time I got the job for the renewal of Linz, in autumn 1940, his directive was, “Preserve the grave of my parents in a small crypt in the lower tower floor.”

Still, Speer’s version of Hitler’s tower-gravesite instigated [historian] Joachim Fest 6 to try to document it thus: "He saw his gravesite in a gigantic crypt in the clock tower of the huge building he planned at Linz, above the bank of the Danube." Fest's notes sourced this as:

“Speer’s personal information. However, one of Hitler’s other favored architects, Hermann Giesler, denies that Hitler wanted to be buried at the clock tower of the building above the bank of the Danube at Linz; only Hitler’s mother would be buried there. Speer, though, remembers definitely Hitler’s remarks that he wished to be buried exactly at that place in Linz."7

That “gigantic crypt in the clock tower" was, in my plans, an octagon room with a diameter of about four meters by five meters high, including the vault. And that vaulted crypt was to be the resting place of Hitler’s parents. It’s all nonsense, even though Fest quotes Speer’s yarn-spinning. But is it that important? Regarding the gravesite itself, not really; but rather in connection with Hitler’s idea to combine his gravesite with the Hall of The Party in Munich. This fascinating connection was the basis of my designs and trial models in autumn 1940, and also the topic of many talks after the city visit of spring 1943.

INDUSTRY, TRAFFIC AND AUTOBAHN

Speer then describes the visit to the Linz steel plants, today the VOEST steel factory, internationally well known. He again describes in a few sentences ‘Hitler’s world of architecture’:

“When we left the large steel hall, Hitler once again expressed understanding for the modern architecture of steel and glass: ‘Look at the tremendous length of this hall over 300 meters long. How beautiful are the proportions! Here we face different requirements than at the party forum. There our Doric style expresses the new order, here the technical solution is the proper way. If one of those supposedly modern architects tells me he wants to build living quarters and city halls in that style, then I say: He has no idea. That is not modern, it is tasteless, and also violates the eternal laws of the art of building. The workplace needs light, air and usefulness; of a city hall I request dignity, and from an apartment house I demand security which helps me to endure the daily struggle. Speer, imagine a Christmas tree in front of a glass wall. Impossible! As everywhere, we have to consider life’s variety.’”

Speer describes by this short rendition what Adolf Hitler said about natural diversity and its consequent distinctions for the design of buildings. Clumsy, and in piecemeal fashion, Speer’s description of Adolf Hitler’s remarks lost the color and strength that, after all, so eminently signified Hitler’s ideas. His thoughts about the necessary security at your home, about the form housing projects should have, about the rationale of a glass wall conveying the hard, sober world of labor compared to the world of sensitive feelings—he mentions the magic of a Christmas tree—all that is missed in Speer’s description.

Yet these remarks of Adolf Hitler comply with the events of our local tours. On the train he discussed with me, as the person responsible for the Linz renewal, questions about traffic, the modern railway station, and the introduction of a wide-rail track. When in the city itself, he spoke about the connection to the Autobahn and the continuation of the Landstrasse with its well-known burgher residences and baroque churches, and the new Laubenstrasse with its street-car system. We were standing at the Danube River—he said, “Giesler will give the river its proper setting; then one can really say Linz an der Donau—Linz at the Danube.” He named the buildings that were to be erected at that beautiful city landscape.

GIESLER VS SPEER VERSION

What Adolf Hitler said, I absorbed, completely fascinated by his descriptions. Speer, however, felt differently. He writes, “Even though Hitler developed his plans with a serious, even solemn, expression, I did not think an adult was talking to me. For a split second, I imagined as if it were a magnificent play with little building blocks.” But why then did Speer push so hard to play with these little building blocks? Why could he never get over that it was not he but I who got the job in Linz, even though I never strove for it?

We drove through the old part of Linz to the housing project and the buildings for the workers of the new factory. Adolf Hitler was shown the different plans for the apartments, he informed himself about the home furnishings, and talked to the workers and foremen. The slightly rising slopes to the West and North of the city favored living quarters. Hitler advised us to look for good traffic connections to the town center and also for the integration of green land. This was for me another reference before Hitler changed from the world of the architect to the blast furnaces, the steel foundries and the rolling mills, and then on to the halls of the Nibelungenwerk , the tank factory where tank officers and weapon experts awaited him. Between the talks about armament systems, Adolf Hitler turned to me, “See to it that the planned granite bridge at the East edge of the city can endure the heaviest loads”—pointing to the heavy tanks.

This puts the lie to Speer’s credo: “I put priority on the overall planning, not the construction of representative buildings; not so Hitler. His passion for monuments of eternity left him completely disinterested in traffic structures, apartment buildings and green space—social dimensions he neglected.” Already during his Landsberg jail time,8 Adolf Hitler was dealing with traffic questions and drawing designs of the Autobahn. Stimulated by his youthful experience in Vienna and Munich and by his study of city planning, especially Paris, his own ideas of city planning developed. They were powerful and modern. With his support of motorization, he put the German street system in order and, at the same time, dealt intensively with the parking problems.

He gave Dr.Todt the job to construct the Autobahn; he created the office of the Inspector General for the German Street System, a unique event in the history of German states. But aside from the individual traffic problems, he was aware of the great importance of the means of mass transportation—in the cities the subway, streetcar tracks, the U and S railway lines.

He saw the crowning solution for track-type railway traffic in the realization of a common European wide-track train system. He requested solutions of the rail-freight traffic known today as container transport. His interest in air technology and air transportation was unquestionable and known to everyone.

SPEER’S PRISON DIARY

“Speer told his interrogators that he had at least sixty different opportunities between January and February 1945 to commit high treason and even made plans, which naturally turned out to be technically impossible, to murder Hitler in his bunker. These were the stories that saved Speer’s head in 1946 and which he now proudly presents again,” writes Barraclough hatefully.9

In his Spandauer Tagebücher,10 Speer describes how the court psychiatrist, Dr. Gilbert, visits him in his cell after the pronouncement of the judgment, wanting to know how Speer accepts the decision. Speer answered, “Twenty years! Well, under the given circumstances they could not have given me a lighter sentence. I cannot complain. I will not complain.”

But one page later he quarrels with his fate. "Should I not have received a lighter penalty, since Schacht and Papen11 went free? I just told Gilbert the contrary. I envy them! Lies, cover ups and false statements did indeed pay off.” And with a reference to Hitler, he continues, “I did not help him into the saddle, I did not finance his rearmament. My dreams belonged only to buildings. I did not want power, I wanted to become another Schinkel.”12

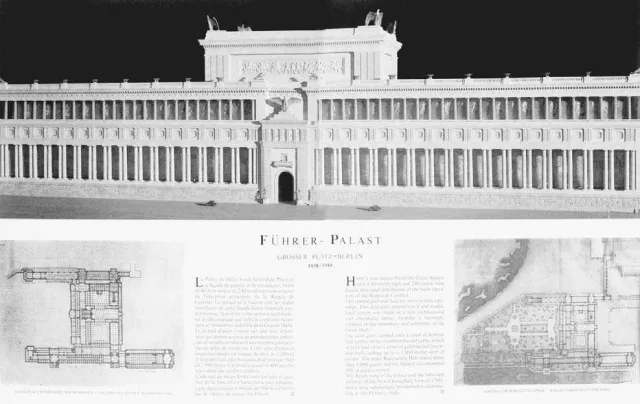

Almighty! This is not small stuff! Well, Speer writes a lot about Gilly and Schinkel, about the Dorian and Prussian style, but his designs for the staircase of the Office of the Reichsmarschall and for the facade of the ‘Fuehrerpalace’ contradict him. Still further on, he writes, “Why did I so stubbornly insist on my guilt. Sometimes I suspect it could have been vanity or boasting. I naturally know that personally I was guilty. But should I have acted that way at the trial? In our world, one survives better by maneuverability and slyness. Could Papen’s cunningness be a role model for me? If I envy him I also despise him. But I was 40 years old when I was arrested, I will be 61 when I leave the jail behind me.”

As far as flexibility, smartness and cunningness are concerned, Speer’s modesty is rather touching for someone who does not know him. In comparison, Papen was no match for him.

So he saved his head but he traded it for twenty merciless years in prison. Twenty years prison—I doubt I could have endured it. Speer certainly did not believe he would be kept that long, with the exception of the last years, because events happened during that time—the Berlin blockade and Korea—which gave him hope for an early release. Speer, no doubt, did not believe in the mischievous harshness of those who, with full intention and severity, insisted on persecution and execution and—God knows—still do it today. He reckoned with the success of the efforts of his daughter, Hilde, and the formal promise of support by Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, Heinrich Luebke, Willy Brandt, Carlo Schmid, Herbert Wehner and Pastor Martin Niemoeller, the Lenin order bearer. He hoped! Even though he wrote in his diary in his 14th year: “…in the evening a hopeful report by Hilde. But these are her hopes, not mine." Well, they were his also.

Endnotes:

1) Nicolaus von Below, At Hitler’s Side, Greenhill, 2001, p 28. Original in German 1980.

2) Christa Schroeder, He Was My Chief, Frontline Books, 2009, p. 159. Original German edition 1985.

3) Maurice Utrillo was an untrained and prolific French painter who specialized in cityscapes of the Montmartre quarter of Paris. His popular scenes are often found on postcards.

4) An allusion to Speer’s preoccupation to be always on Hitler’s right side which is considered to be the preferential side.

5) The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of reform-minded English artists and critics who scorned the academic art of their day (1850’s).

6) A German historian, journalist, critic and editor who was a leading figure in the debate about the Nazi period.

7) Joachim Fest, Hitler, Berlin, Propyläen, 1973.

8) Hitler spent nine months in Landsberg Prison in Bavaria following what is called the “Beer Hall Putsch” in November 1923.

9) Geoffrey Barraclough, “Hitler’s Master-Builder,” The New York Review, 7-1-1971.

10) Albert Speer, Spandauer Tagebuecher (Spandau Diaries), Verlag-Ullstein, 1975.

11) Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president 1933-1939 and Minister of Economics 1934-1937. Franz von Papen, Chancellor of Germany June 1-Nov. 17, 1932.

12) Karl Friedrich Schinkel, a Prussian architect, city planner and painter who died in 1841 is one of the most prominent architects of Germany, known for both neoclassical and neogothic buildings.

- 7367 views

architects

Family of Behrens

I have been glued to your site for two days now. I am glad I found it. I have always wanted to know more about my people other than we are evil blue eyed devils. I cant seem to find much on my family's past at home so was searching around and found your site. All I can say is super thanks for this infromation.

You are a true blessing