The Final Flight of Poldi Wenger - April 10, 1945

The Final Flight of Poldi Wenger - April 10, 1945

Today is the 70th Anniversary of the death at age 23 of Oberleutnant Leopold Wenger, Jr after over 400 combat missions in the defense of the Reich. At the time of his death, Poldi was Squadron Commander of Schlachtgeschwader 10/Jagd 2 stationed at Markersdorf airfield near St. Pöltan, close to Vienna. In this year of 2015 with so many 70th anniversaries relating to the end of World War II going on, this one should not go unnoticed.

To honor Poldi, I am presenting this report, in a somewhat edited form, written by his younger brother, Willy Wenger, about Willy's search for information on Poldi's last days and the dogfight above Vienna with Russian fighter planes that brought about the belly landing by the seriously wounded pilot and Knight's Cross holder. See here for more background. As fate would have it, April 10 was the birthday of Leopold Wenger Sr., who had an especially close bond with his first-born son.

My Investigation

by Willy Wenger

copyright 2015 Carolyn Yeager

Spring 1997

The winter of this year was particularly long-lasting and a lot of work was waiting for me in the garden. No sooner had I made up my mind to dig up a very extensive root stock than a policeman in uniform came into our garden. He waved his hand when he noticed my puzzled face. I could not explain his appearance. Had I been up to something?

No, the young man smiled and assured me that he had not come on a service action, but on a private matter. He had learned that my father had performed service in the Austrian Navy and he was keenly interested in Austrian seafaring. I wanted to dismiss him immediately! This was all I needed, to be interrupted from my hard work that I wanted to continue. But the young man persisted and asked that we sit down together after work. Herr Franz Mittermayer from Trautmannsdorf was the district inspector at the Gleichenberg police station and an avid amateur diver who had been to various seas and oceans in search of shipwrecks of the last two wars. He showed a special interest in my father, and the Austrian navy.

Willy and Police Inspector Franz Mittermayer in 1997 looking over shipwreck photos and diaries of Leopold Wenger Sr.'s naval career.

Eventually we met more often and evolved a very good friendship. I found my father's war diary and showed Herr Mittermayer his photos and he also had photo albums about his maritime explorations. I then got so much into this work that I put together some reports about this time and was surprised that I could manage it. But I asked myself, Why am I doing this work? The Navy does not interest me so much, I lean more toward aviation now, and especially since the career of my older brother “Bibi” (better know to his Luftwaffe comrades as “Poldi”) with whom I had excellent letter contact during the war years – until it was suddenly terminated.

I had already begun in the spring of 1946 in the search for the whereabouts of my brother. Our family received a letter only in October 1945 that had been written by Poldi's group commander Major Götz Baumann at the end of April 1945, but which had been retained by the Allied military censorship, telling us that my brother had not returned from a sortie during the last days of the war and was since then considered missing.

So in the spring of 1946 I was on my way to Hofgastein to see Herr Loidl, one of Poldi's squad mates. I was hoping to learn from him some details about my brother's crash. I met him in his home and he told me of a place where he had seen a crash of a Fw 190 from the air, in the area of Amstätten. I went there but it was not easy because it was in the Russian zone of occupation. At that time, we had identity documents in four languages and there had to be exactly 13 stamps on them, which the Russians counted carefully. There were 13 and so everything was fine.

I left the train in Amstätten and went on foot to search and comb an area of about one hundred square kilometers (5x20km). I inquired of the rural population if any remembered an airplane that crashed about a year ago. Two young boys led me to a crater in the middle of a freshly plowed field and there I found some debris – a burned wreck of an aircraft – and took a few small pieces. But it turned out later that it was another German pilot who died there.

At that time we lived from one day to the next, the idea was “just survive.” Everything was reduced to rubble. It was therefore necessary to rebuild the country and to look for a job and have a job. I first worked for two years as an apprentice roofer. Later I moved to the tourism industry and attended the Hotel School Bad Gleichenberg. I worked in Switzerland, in Italy and for nearly a decade in Africa (Tunisia and Kenya). I had no time to spend in investigation. Only when I retired, the idea came to me to investigate where Poldi spent the last months of the war. Although I had two flight books from him, of which the second to last ended in August 1944, the very last one was missing. I could tell from his flight books where he flew missions and where his unit was. Also some existing letters showed me that he had flown missions in Romania, Ukraine, Poland, Serbia, Hungary and, most recently, in Austria.

Through Herr Mittermayer I learned of Herr Erwin Sieche, publisher of navy books. I told Sieche that I had tried in the Austrian literature and archives to learn of the last missions of the Luftwaffe in Austria, but without any success. He advised me to turn to Walter Schroeder, a flight historian in Vienna and editor of an Austrian aircraft history magazine. Schroeder had good connections in Germany and gave me several addresses which could possibly help me. They were:

- The Search Service headquarters in Lohmar near Cologne

- The German Air Force in Bonn

- The Order of the Knight's Cross in Berlin

I wrote to these sites.

The Search Support Center published an ad in “Hunters Journal.” The Air Force ring sent me excerpts from the book “The Knight's Cross of the Luftwaffe (Stuka and attack aircraft).” I got hold of the book which featured the German Stuka aces 1939-1945, in which Poldi was mentioned. The Air Force Ring also published a search message board in the Air Force Revue. The Congregation of the Knight's Cross willingly gave me addresses of former pilots of the Battle Squadron SG10. Among them was the name of Erhard Nippa, which I remembered from a letter to Poldi in 1943 from his group commander, Capt. Heinz Schumann. From Herr Heinze in Berlin I got Nippa's address. He answered me immediately upon receiving my letter and told me that he was three and half years together with Poldi. He said about my brother, “Poldi shoots as fast as any.” He said it was spoken about in the entire squadron that Poldi had fallen victim to an insidious trap. At that time, every now and then Russian and also Hungarian pilots had flown captured Fw 190's to deceive the German pilots. Nippa proposed to say more about it during a personal meeting.

Poldi mentioned in his log book once the name of his wing leader with whom he had flown other missions as Katschmarek [wingman] – Oberleutnant Fritz Schröter. From Herr Heinze I got his address in the Allgäu. He was reticent at first but when he understood I was Poldi's brother, he became talkative and even wanted to give me Obermaier's book if I did not have it. Schröter was handed over to the Russians by the Americans at the end of the war and spent 3 years in Soviet captivity. On his return to Germany, he was involved in the founding of the Bundeswehr as a teacher in service to the new German Air Force. He sent me a picture of Staffel 10/JG2 with all the pilots, mentioning in passing that the tall Ensign behind Poldi, Gerhard Limberg, has become one of the inspectors of the new air force. But because he was so soon removed from the [English] Channel and moved to a North Africa group, Schröter referred me back to Nippa.

Nippa told me about Capt. Frank Liesendahl, the squadron commander of the 10th Jabostaffel, Fighter Wing “Richthofen” – about the shoot-down of Liesendahl by English navy anti-aircraft. A couple months later, his body was fished out of the sea by an English ship, identified and then returned to the water. Poldi was greatly moved by his loss, when he told us about it in a letter without mentioning the name of his boss. So I first learned from Nippa about Liesendahl being the one who created the new idea of quick surprise attack in low-level flight just above the waves, to escape the British radar. It was later known as the Liesendahl Method. Oberleutnant Schröter was Liesendahl's successor as Commander.

Nippa also sent me a very interesting article from 1942 by a former war correspondent, and suggested a meeting at his home in Belheim for a personal conversation.

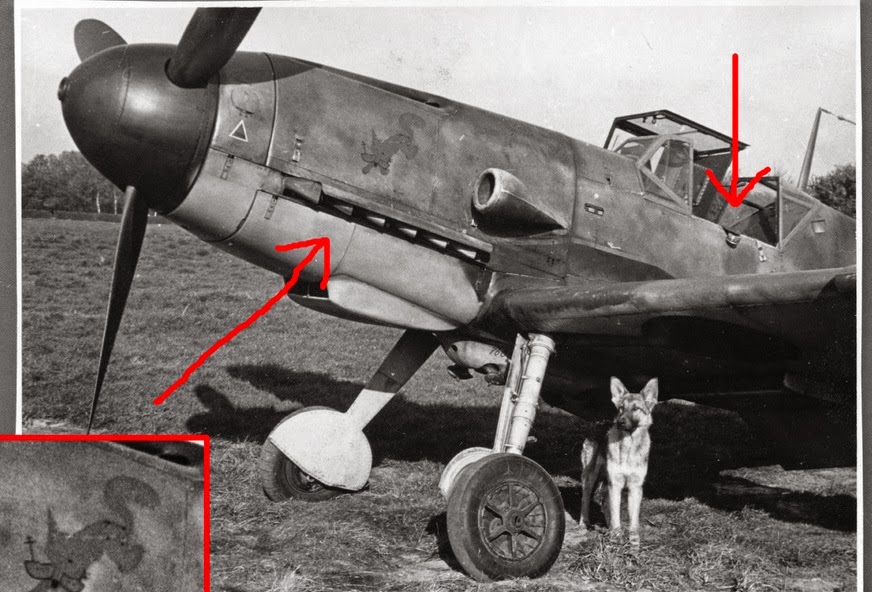

A search message in the Air Force Revue brought a letter from Herr Hans Riegler of St. Pöltan. He asked if Poldi was stationed at the airfield of Markersdorf, a village near St. Pöltan. He had been a pupil at the NAPOLA Theresianum in Vienna and had an interest in the very last missions of the aircraft from Markersdorf. He has extensive knowledge of the units stationed there. After our first phone call, he drove to Vienna and visited Poldi's grave in the Vienna Central Cemetery, photographed it, and even cleaned the gravestone and laid flowers. He has greatly helped me time and again during my research. I learned from Herr Riegler that it was General Dessloch, Chief of Luftflotte 4, who presented Poldi with the Knight's Cross. Riegler also found documents relating to the time of Hptm. Liesendahl and brought me a series of pictures, including the Fw 190 with the squadron insignia of red foxes on the machine.

Also from the Air Force Revue came a letter from Mr. Jean Roba from Charleroi saying he knew of a few people from the SG/10 and has a connection with one of the former pilots, W. F. Grunewald, who became a Brigadier General of the new German Air Force, and probably knew my brother. I contacted General Grunewald at the address given and learned that he and Poldi were in the same staffel. From him I also learned that Poldi had been transferred to a battle flying school for Knight's Cross holders and Grunewald took Poldi's place as squadron leader. This was completely unknown to me before now. In early April 1945, the school had to close and Poldi returned, becoming again squadron commander of the Red Foxes. On April 8, Grunewald was shot down over the Vienna Woods. He did not know until I told him (55 years later) that Poldi had been shot down just two days later.

An interesting aspect of this I learned from a meeting between Dr. Jürgen Schreiber. Erhard Nippa and General Grunewald. Rudolf Neugebauer from the Stuttgart area recalled witnessing Grunewald being fatally shot on April 8, 1945 when he accompanied him as Katschmarek against Russian tank formations in the Vienna Woods. He was flying behind Grunewald when G. was attacked by Russian Lagg 5 hunters; Grunewald's plane crashed and exploded on impact. What Neugebauer did not see was that Grunewald, though wounded, was able to exit by parachute, was rescued and taken to the hospital in Bad Hofgastein. Neugebauer couldn't believe it when he heard my report, and he visited him and welcomed him again – after 53 years.

In response to a search, Horst Willborn wrote me from Hamburg. A former schoolmate of Poldi's from Köslin (NAPOLA), they had met by chance in 1943 in southern Italy. He said he has passed the information about Poldi to Gilbert Geisendorfer, who was Poldi's best friend in school in Leoben. Geisendorfer was squadron commander in combat squadron 53 “Legion Condor” where Willborn also worked as an intelligence officer. Gilbert was awarded the German Cross in Gold, was in the Battle for Stalingrad and still meets every year with his former aircrew.

The Bf 109 belonging to Frank Liesendahl whose fiance designed the "red fox" emblem for the planes of the 10 Jabostaffel "Richthofen".

From Nippa, I learned a lot about their squadron commander Frank Liesendahl, who initiated the fighter-bomber private method, the “Liesendahl method.” He was killed on 17 July 1942. At the time, he was engaged to a Miss Arnold, a graphic designer at Messerschmitt. It was she who designed the emblem of the red fox, since used on all the planes of 10 Staffel. Poldi, Nippa and Schröter were all invited to the upcoming wedding. The couple had a son who never knew his father; he goes by his mother's name, Arnold. Today Dr. Prof. Frank Arnold (right)  is one of the leading German scientists and researchers for the Atmospheric and Nuclear Physics division at the Max Planck Institute at the University of Heidelberg. Prof. Arnold and I maintain a very pleasant and friendly contact via letter and telephone. He sent me a series of photos of his father and a few interesting and very impressive, well-preserved 8mm films that show life inside of Jagdgeschwader Richthofen. Also excellent scenes in formation flight with Me 109s and Fw 190s. He also gave me copies of the outstanding pictures that his mother had painted or drawn.

is one of the leading German scientists and researchers for the Atmospheric and Nuclear Physics division at the Max Planck Institute at the University of Heidelberg. Prof. Arnold and I maintain a very pleasant and friendly contact via letter and telephone. He sent me a series of photos of his father and a few interesting and very impressive, well-preserved 8mm films that show life inside of Jagdgeschwader Richthofen. Also excellent scenes in formation flight with Me 109s and Fw 190s. He also gave me copies of the outstanding pictures that his mother had painted or drawn.

Robert Wagner often calls me from Nuremberg; he came to Poldi's unit in the spring of 1945 from the Stukas. As did Ernst Orzegowski from Hamburg - he was at the Stukaschule in Graz in 1941 and often flew over Bad Gleichenberg. I was at that time a young Pimpfe on the ground, every day eagerly watching the training dives of the daring pilots. Orzegowski once made an emergency landing close to us, and another time in Fehring, which was also close by. He is one of the few pilots who has been shot down 15 times and survived the war without wounds.

In my research I came across a book with a report on the Knight's Cross holder Oberfähnrich Erwin Gutzmann. I learned that he was shot down on the same day as Poldi, 10 April 1945, during a mission originating from St. Pölten, and after making an emergency landing bled to death from a wound, just as Poldi. I told my friend Hans Riegler about this and he immediately inquired in detail about it. He was shown the landing site, the cemetery where Gutzmann had been buried (before being transferred to a military cemetery), and even found witnesses who could still remember quite well this emergency landing. A farmer had salvaged the tail wheel of the Fw 190 and used it for his wheelbarrow. The farmer's son had kept the wheel in the corner of his barn and gave it to Riegler. We then tried to find Gutzmann family members, but without success. [April 10, 1945 was a fateful day when two Knight's Cross pilots on missions from Markersdorf airfield were killed. -cy]

I told Herr Rauchbach of the event of Poldi getting shot by a British Spitfire, resulting in a 2 cm hole in his gas tank and of his reaching home only with difficulty. Rauchbach searched in the English Battle reports and determined that the shot came from Canadian pilot Barry Needham. He sent me a few photos of Needham and his colleagues from an English site.

Now I was understanding the whole process pretty well. I was always in such good contact with my brother, who was very busy but made time to write. But then, from the beginning of 1945, the post was not as accurate and as of February I knew next to nothing of where my brother was deployed and how his life evolved. Now I had the information through Grunewald that Poldi joined the SG 103 school squadron and became a flight instructor in this connection. But it was quite difficult to learn anything definite. Very often I was told that the man I was asking for was in the hospital or had just survived a heart attack, or was even deceased. At a Knight's Cross meeting in May 2000 on the Attersee, I was invited and got to know some people personally. From Colonel Hermann Buchner I learned that Poldi's dogfight over Ploesti, Romania was on 23 June 1944. This was the first use of numerous U.S. Bombers coming from Italy to bomb the oil fields of Romania and Russia. In this battle Poldi was shot down, and was barely able to make an emergency landing in a field.

Finally I found in some archival documents, with the help of Willi Kriessmann, that Poldi was with the SG 6 Staffel at the Ritterkreutz [Knight's Cross] school. I was able to speak with Colonel Charles Kleckl from Vienna on the phone, and although he was very cooperative, he travels constantly between Vienna, South America and South Africa. But from early February '45 to early April, Poldi was probably working as a flight instructor for the next generation of pilots.

UPDATE: From Willy Wenger on 4-11-15

Poldi had been Staffelkapitän of the 4th Staffel of the Schlachtgeschwader 10 for some time already. It was the practice to take out experienced pilots from the fronts as teachers in “school-Geschwaders.” Each schulegeschwader began with the number 100 – so Poldi's school was named Schlachtgeschwader 103 at Fassberg airbase in Lower Saxony. In the meantime, Oberleutnant Wilhelm Grunewald became the leader of the 4th Staffel/10 as Staffelführer (not yet Staffelkapitän). As Allied troops approached Fassberg, the school was closed and Poldi returned to his SG 10 unit at Markersdorf in the last days of March or first days of April 1945. According to Nippa, the Group Commander decided in a conference to reinstate Poldi as Staffelkapitän, with Grunewald as his assistant.

Markersdorf was one of the last airfields of the Luftwaffe where aircraft could still land and take off.

Another coincidence: Loidl was a pilot in Poldi's squadron for 3 years. A few months ago, his son, a professor, got in contact with me after reading one of my reports in an Austrian flying paper and we will meet together next month. And just yesterday I received a long letter and book from the daughter of Spitfire pilot Barry Needham from Wynyard, Saskatchewan.

* * *

In Spring 2001, I received an email from Barry Needham, brokered by the Englishman Chris Goss, in which he writes that he would like to get in touch with me, but was a bit cautious. He had believed that Poldi had been shot down in that aerial combat with him, and felt involved in his death. It was with great relief that he learned from me that despite severe damage, Poldi could still return to his place of origin. Now he is only sorry that he could not meet Poldi; he is of the opinion they would become very good friends. Barry lives in Saskatchewan, Canada and we have since then maintained an intensive traffic via email. In May 2001, I had a visit from my younger brother Gerd Wenger from Bern. He brought me on my 75th birthday a gift of the joystick of the Fw 190 belonging to our older brother, along with the 2 cm projectile from the Spitfire cannon mounted on a base by our father who had engraved the date 17-9-1942 (Sept. 17, 1942). Yes, it is the actual projectile Barry Needham had fired.

On 11 October 2001, I get a call from Mr. Eric Mombeek from Belgium. A historian with the University of Brussels, he has written several books about the Luftwaffe and is very interested in the documents that I have about my brother. At a very amicable meeting in Vienna, I show my photos for copying by him and learn a lot of new and interesting things from our talks.

In early May 2002, I get from Erhard Nippa the address of Sepp Fröschel, a former pilot and comrade of my brother and a Vienna native. At the end of May 1942, he was shot down in a dogfight over the Isle of Wight and taken as a prisoner of war to Canada. After the war, he earned his doctorate there and became a professor of mathematics at the University of Montreal. From him I learned some very interesting details about the squadron of the “Red Foxes” and their operations against the British warships on the south coast of England.

In September 2004, Barry Needham, his wife Martha and daughter Denise arrived in Bad Gleichenberg. As a gesture of friendship, I gave to him the mounted bullet that he fired at my brother's plane 63 years earlier. With tears in his eyes, he took it gratefully and asserted how happy he is now that he knows that my brother was able to escape his attack and he is not guilty in the death of his opponent, adding he admired how masterfully Poldi carried out maneuvers in intense combat.

Through a variety of connections, I became acquainted with Dr. Maurice Shnider of Canada, who at 82 was still an active physician. We maintained a friendly contact through email and phone; he invited me to come to Winnipeg where he owns a large house. Dr. Shnider now knows Barry Needham personally and both are eager that I should visit him and his wife; they want to show me much of Canada. Maurice said on the phone: “We will fly with a small seaplane to one of the numerous lakes and then we will have a fishing lake all to ourselves.”

From my research has come more that I ever expected. My success would not have been possible had not the persons mentioned above largely supported and helped me. Through them, I now have a comprehensive, almost complete picture of the last period of my dear brother's life. Of all the interesting personalities I have met, with each one upright and honest friendships have been formed - men who have nothing to reproach themselves for, though many indignities were exposed after the war. Hardly anyone has survived unharmed. Some had to languish years in Russian captivity. Men who still speak respectfully of their former enemies have found these comrades on the other side and, through understanding, have become friends. Commendable are those who testify with great reverence, respect and recognition of the German soldiers. Even in the foreign literature [military -cy] is found objective reporting and the possibility of a largely accurate orientation.

What pleases me most: I have been able to establish excellent ties of friendship among former adversaries. And that alone was worth my investigation work.

Bad Gliechenberg, summer 2004

- 2372 views

Comments (4)

Real men, Real Women, Real Reich.

endzog

How manly the men and feminine the women, and healthy in mind souls and body the children of the Reich. How real diversity in sexual roles, real diversity in races and nations, brings harmony to nature to spite the degenerate wars of the sexes, races and nations which is the work of the Jew. May the parasite enemy of God and mankind, the enemy of nature and truth the Jew be defeated. May the future belong to us and it's monuments be ours and not theirs:

https://endzog.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/93.gif?w=510&h=471

"http://carolynyeager.net/" not accessible from Germany

Peter

Hi Carolyn,

I´m able to access this site via TOR browser which gives me a random IP; however, when I try to access the site with the normal browser, i.e. my usual IP, from Germany, I get this message:

"Sorry, 108.162.254.197 has been banned.".

Not an expert and no idea if it means much, or might be ok again tomorrow.

Just reporting, and you may want to have a look into that. Cheers, and as always great thanks for all your work, Peter

Mistaken blocks

carolyn

Thanks for telling me, Peter. I did find that IP on the blocked list and removed it.

I have a blocked list a mile long! Whenever I get spam I put it on there. So maybe things get on there by mistake but I don't ever put a block on real people just because I don't like what they say or don't post their comment.

There were a whole lot of 108.162.254's on the list. It might be when blocking one, a whole slew of them get blocked along with it? I encourage anyone who is having this problem to let me know via the contact form, or at [email protected] so you don't have to reveal your IP number. I will be happy to check it out. You are not the first friend of my site who got onto that list ... somehow.

My administrator even found his own IP on there! That was an interesting conversation between us that followed, lol.

Carolyn, I can access the

Peter

Carolyn, I can access the site again. Interestingly, the named IP "108.162.254.197" is for San Francisco (United States - California), according to some http://www.localiser-ip.com ... so I luckily didn´t accidently publish my IP here.

I´m glad it was only a block caused by your anti-spam list as I thought that somehow your site had been banned ! But since not an expert, I wouldn´t know what your site-IP would be etc. In any case, all good again.