100 years ago: A German "triple triumph" established U-boat warfare

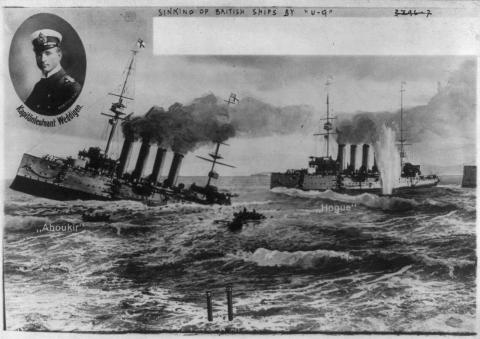

"Victories of U-9" - a contemporary German postcard showing the photo of Weddigen against the background of the sinking "Aboukir" and "Hogue".

On September 22, 1914 Lieutenant Otto Weddigen sunk three British armored cruisers. He was the first war hero for Germany.

A mere 600 tons of water was displaced when the Imperial U-boat "SMS U9" was immersed. Only 60 meters long, the boat had a driving force of about 1000 hp – not particularly strong. Although only four years old in September 1914, it was already outdated because it had petrol instead of more powerful diesel engines to power itself over water.

The three Goliaths the "U9" sighted in the early morning of September 22, 1914 were even older, but each was 144 meters long, with 12,000 tons displacement, 23.3-inch guns and 760-man crews,

Not the latest battleships of the British Home Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet, certainly—but each of these ironclads was deadly dangerous for a single small submarine anyway. Unless several special circumstances came together. That was the case on this Tuesday.

Bad weather in the English Channel

The cruisers Group C of the Royal Navy was given the task of patrolling the Channel up to The Hague—as part of the naval blockade that Britain had imposed immediately after the start of the First World War against Germany. And their cruisers were to run at one and a half miles distance from each other on parallel courses to the North-East, then turn around and drive back to south-southwest. A standard maneuver they trained countless times.

But nothing was normal in these days of September, 100 years ago. Bad weather had forced the accompanying destroyers to turn off –they could not keep up with the great battleships in the heavy seas. Then the flagship of the group, the "HMS Euryalus" turned off because the coal supply was running low. All that remained were the "Aboukir", the "Cressy" and "Hogue," now commanded by Captain John Drummond as the longest-serving ship commander of the three.

Although on the evening of September 21, 1914 the weather cleared, Drummond had not called his destroyer—a mistake with fatal consequences. He also decided not to let his ships run zigzag—in addition to destroyers, the surest protection against submarine attacks. Although the maneuver cost speed and exhausted the teams, it also increased defense capability.

The following morning when the commander of "U9", Lieutenant Otto Weddigen, sighted the huge columns of smoke of the three armored cruisers, he could hardly believe his luck: Without a destroyer, in a reasonably calm sea, three enemy ships were running directly to him. Rich booty.

David and Goliath

Weddigen's job was difficult enough: On 19 September 1914 he had run out from Helgoland. His destination was the English Channel at the level of the Maas estuary. Here he was, all on his own, attacking British blockade ships. A battle of David against Goliath.

The Goliaths felt too safe. Drummond did not notice that "U9" was brought into a favorable firing position. At 6:25 in the morning the first torpedo hit the "HMS Aboukir" portside and damaged it severely. Immediately the other two cruisers set sail toward the sinking sister ship. Their commanders believed Drummond's ship had hit a mine.

Captain Robert W. Johnson of the "HMS Hogue" for safety's sake looked out for a submarine periscope, but only on its starboard side. Weddigen had wisely maneuvered and reached the second cruiser also on its port side. Two torpedoes took down the ship in ten minutes.

The "HMS Cressy" with Captain Wilmot Nicholson sailed for the two sister ships. At 7:20 the "U9" fired two torpedoes, one of which went wrong, the other caused only slight damage. Now Weddigen had exactly one weapon left. He turned his boat and shot from the aft torpedo tube for a direct hit. A total of 1,459 British sailors drowned, only 837 were rescued.

Weddigen returned as a Winner back to his home port of Wilhelmshaven. The 32-years-old commander was immediately the center of a hero cult. The International Maritime Museum in Hamburg, which secures the estate of Weddigen and will inaugurate an exhibition on underwater warfare 1914-1918 in October, documented this enthusiasm.

The crew of "U9" were showered with gifts; children recorded the success over the three ironclads; postcards with photo montages of the battle became bestsellers.

The conclusions of the Admiralty

The leadership of the Navy took from the success of Weddigen the conclusion that submarines could defeat any opponent. Until then, the focus of the German plan had been on the use of capital ships. Now, immediately available small and much less expensive submarines were seen as the better offensive weapon, especially since the arms race in capital ships had already been decided in favor of the British years before the war's outbreak.

Without this change of mood in the Imperial Admiralty, it might not have come to unrestricted U-boat warfare, which was first operated briefly in 1915 and in 1917 officially proclaimed. But it led to war with the United States, thus changing the relative balance of Entente and Central Powers.

Weddigen did not experience this time. In early 1915, he got a new submarine, but with a different crew, the "U29". On the first patrol he sank four freighters. But then "U29" came into the vicinity of the British Home Fleet. Their previous flagship "HMS Dreadnought" took to hunting and after several maneuvers rammed "U29." The boat pulled all hands on board, but in the end, Goliath kept the upper hand.

From http://www.welt.de/geschichte/article132390591/Dreifacher-deutscher-Triu...

HMS Dreadnought at sea, 1906

Category

European History, Germany, World War 1- 5151 reads