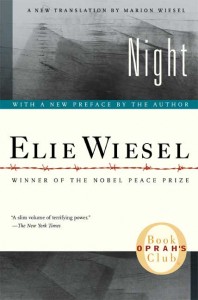

An in-depth investigation into the source of Elie Wiesel’s famous “first book.”

By Carolyn Yeager, August 2010

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

In literature, Rebbe, certain things are true though they didn’t happen,

while others are not, even if they did. … Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea

(autobiography)

Part One: When and how was Un di Velt Hot Gesvign written?

The question I present to you, the interested public is: Was Night, a slender volume of approximately 120 pages in its final English-language form, written by the same person who wrote its original source work: the reputed 862 typewritten pages of the Yiddish-language Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent)?

This is an important, though not crucial, question as to whether Elie Wiesel is an imposter. The evidence that I have uncovered so far is however, even on this question, not in his favor.

Naomi Seidman, professor of Jewish Studies at Graduate Theological Union, wrote a controversial article about Elie Wiesel titled “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage.” In that article, she mentions a 1979 essay by Wiesel, “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” that contains the following on page 15:

“So heavy was my anguish [in 1945] that I made a vow: not to speak, not to touch upon the essential for at least ten years. Long enough to see clearly. Long enough to learn to listen to the voices crying inside my own. Long enough to regain possession of my memory. Long enough to unite the language of man with the silence of the dead.”1

Just as an aside, I have to wonder whether these are believable thoughts for a 16 year old? And why wouldn’t his memory be better immediately, rather than 10 years hence?

In the essay, Wiesel also explains that his first book was written “at the insistence of the French Catholic writer and Nobel Laureate Francois Mauriac” after their first meeting in May 1955 when Wiesel had obtained an interview with the famous writer and the subject of the Holocaust had come up. Wiesel told him he had taken a vow not to speak, but Mauriac insisted he must speak. “One year later I sent him the manuscript of Night, written under the seal of memory and silence.” 2

As far as I can tell, there is no mention in this 1979 essay about writing the almost 900 page Yiddish manuscript while on a ship headed for South America. This particular essay is not available on the Internet, and Seidman is one of the few that even mention it.

In his 1995 memoir, All Rivers Run to the Sea, Elie Wiesel gives a more complete description of his first attempt to record his camp experiences already in 1954, before the ten year vow of silence was up. Wiesel is always stingy with dates, and gives no exact month for the ship crossing, but from later comments about when he returned to Paris, we can place it in April 1954. Beginning on page 238:

I was sent on several European trips related to the Israeli-German conference on reparations, then to Israel, and finally to Brazil.

His assignment was to check out ‘suspicious’ Catholic missionary activities toward Jews.

My poet friend Nicholas proposed to go with me. A resourceful Israel friend somehow managed to come up with free boat tickets for us.3

Before he continues writing about the trip, he interjects a full page about a romance with Hanna, who wants to marry him, and whether he should. He tells her he will be gone 6 weeks—he is glad to have the time to think it over.

These questions haunted me during the crossing. I was worried sick that I might be makng the greatest mistake of my life. Should a man marry a beautiful, intelligent, and impulsive woman with a marvelous voice, just because he had once loved her and because she had now proposed to him? And because he did not want to hurt her?

Then, the very next paragraph:

I spent most of the voyage in my cabin, working. I was writing my account of the concentration camp years—in Yiddish. I wrote feverishly, breathlessly, without re-reading. I wrote to testify, to stop the dead from dying, to justify my own survival. I wrote to speak to those who were gone. As long as I spoke to them, they would live on, at least in my memory. My vow of silence would soon be fulfilled; next year would mark the tenth anniversary of my liberation. I was going to have to open the gates of memory, to break the silence while safeguarding it. The pages piled up on my bed. I slept fitfully, never participating in the ship’s activities, constantly pounding away on my little portable (see comment #1 below), oblivious of my fellow passengers, fearing only that we would arrive in Sao Paulo too soon.

We were there before I knew it. 4

There is no lead-up in All Rivers Run to the Sea that his concentration camp “testimony” was heavy on his mind; this paragraph just jumps out of the blue. And it’s all he wrote, in a 418-page memoir, about the process of putting down the most important words he would ever write. But no! It seems clear from this that the finished words of La Nuit were the most important words he would write, and that he had a hard time knowing what to say about the writing of the “original” manuscript. So he brushed it off in one paragraph.

We get a very contrasting picture of Wiesel’s writing style in his Preface to the 2006 new English translation of Night by Marion Wiesel, his wife. Referring to his awareness [at that time] that he must bear witness, he writes:

Writing in my mother tongue [Yiddish]—at that point close to extinction—I would pause at every sentence, and start over and over again. I would conjure up other verbs, other images, other silent cries. It still was not right. But what exactly was “it”? ”It” was something elusive, darkly shrouded for fear of being usurped, profaned. All the dictionary had to offer seemed meager, pale, lifeless.

[…]

And yet, having lived through this experience, one could not keep silent, no matter how difficult, if not impossible, it was to speak.

And so I persevered.

[…]

Is that why my manuscript—written in Yiddish as “And the World Remained Silent” and translated first into French, then into English—was rejected by every major publisher …

[…]

Though I made numerous cuts, the original Yiddish version still was long. 5

Here, Wiesel tells us that he agonized over the writing of the Yiddish manuscript, and it was slow going. He even consulted the dictionary. But his time on the ship could not have been more than 2 weeks of the planned 6-week voyage to Brazil. In All Rivers Run to the Sea, he claims to have written 862 typewritten pages during that time, when he had to also eat, sleep and take care of other essentials. So of necessity he says he wrote feverishly, without re-reading. It leaves the two accounts as total contradictions.

When the ship docked at Sao Paulo, his friend Nicholas, an Israeli citizen, disembarked. But Elie, as a stateless person, was prevented from doing so by some “red tape.” Then he noticed a group of about 40 Jews from Palestine who had been “lured” over by the promises of Catholic missionaries, who also were not allowed to disembark. He makes the decision to join them and write their story for his newspaper. After traveling to several ports (Wiesel is now relegated with the unwanted Jews to staying in the ship’s hold), the boat docks at Buenos Aires, Argentina. It just so happens that in Buenos Aires a Yiddish singer came onboard with Jewish book publisher Mark Turkov. Wiesel shares his concern about the Jewish exiles, for whom he had become spokesman, with Turkov, and then:

As we talked, Turkov noticed my manuscript, from which I was never separated. He wanted to know what it was and whether he could look at it. I showed it to him, explaining it was unfinished. “That’s all right,” he said. “Let me take it anyway.” It was my only copy, but Turkov assured me it would be safe with him. I still hesitated, but he promised not only to read it, but “If it’s good, I’ll publish it.” Yehudit Moretzka (the singer) encouraged me by telling me she would make sure the manuscript would be returned to me in Paris, with or without a rejection slip. I was convinced Turkov wouldn’t publish it. I couldn’t see why any editor would be interested in the sad memoirs of a stranger he met on a ship, surrounded by refugees nobody wanted. “Don’t worry so much,” Yehudit told me as she left. But I felt lost without my manuscript. 6

This is the last that is said of the manuscript. Wiesel goes on to write about the positive outcome for the “exiles” and himself to go ashore in Sao Paulo, and Hanna’s letters which had piled up in the American Express office there. No further communication with Turkov is reported or any mention of his manuscript until 35 pages further on. It’s back to the business of journalism.

I had been away for two months when Dov recalled me to Paris to cover Pierre Mendes-France’s accession to power. I flew back, anxious to see Hanna. I would explain the exceptional circumstances, find a way to make her forgive me. She would understand, for I had missed her. I would tell her that I had been faithful to her, even in my thoughts.7

Handing his only copy (see comment #1 below) of the manuscript over to Mark Turkov in this strange manner appears to be an attempt to explain why Wiesel does not have possession of the original Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, but it is not convincing to me that he would turn such a “sacred –to him—soul work,” embodying his commitment to “witness for the dead,” over to strangers in a foreign country with only a vague promise that it would be returned. He is first consumed by it, then careless of it. He adds his professed belief that Turkov would not be interested in it and would never publish it. Why then part with it—and feel lost without it? Like so much of Wiesel’s writing, it stretches the limits of belief.

Even more, he says it was not completed to his satisfaction. There are several things Wiesel is likely trying to account and cover for with the ship book-writing story: (1) the incredible length of this manuscript and the short space of time he had to write it; (2) a way to get it into the hands of an Argentine Yiddish publisher in 1954; and (3) his lack of ever being in possession of the original and even being relatively unfamiliar with it. Writing in such a “feverish state”, without re-reading (impossible!), leaves him free to have no clear idea what was in it.

Several pages further on in All Rivers Run to the Sea, Wiesel writes about his meeting and relationship with Francois Mauriac:

He wrote of our first meeting in his column of Sat. May 14, 1955, referring to a “young Israeli who had been a Jewish child in a German camp.” Of course, I wasn’t Israeli. Perhaps in his mind, Jews and Israelis were the same thing.

I owe him a lot. He was the first person to read Night after I reworked it from the original Yiddish.8

Wiesel is telling us that “he” did the editing from the “original Yiddish.” He says the same in the Preface to the new 2006 translation of Night: “Though I made numerous cuts, the original Yiddish version still was long.”9

But when did he do this editing?

Mark Turkov, from whom I have not found one word of confirmation for the ship scene with Elie Wiesel, must have reduced the 862 pages to 245 pages himself because he published it in the same year, 1954, in his 176-volume series of Yiddish memoirs of Poland and the war, called Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry, Buenos Aires, 1946-1966).10

The next and last mention of Mark Turkov and the manuscript in All Rivers Run to the Sea again pops up as less than a paragraph in the midst of Wiesel’s busy schedule and after the breakup of another love affair, with Kathleen this time, in the summer of 1955. He writes:

In December I received from Buenos Aires the first copy of my Yiddish testimony “And the World Stayed Silent,” which I had finished on the boat to Brazil. The singer Yehudit Moretzka and her editor friend Mark Turkov had kept their word—except that they never did send back the manuscript. Israel Adler invited me to celebrate the event with a café-crème at the corner bistro.11

That’s it, believe it or not. This is obviously something Wiesel is not interested in focusing attention on. Because none of it is true?

The timing also requires that after Wiesel received the Yiddish book from Turkov in December ’55, he managed to translate the 245 pages into French for Francois Mauriac, and present it to him in May 1956–as Wiesel testified in “An Interview Unlike Any Other.”

What can we believe?

Certainly Elie Wiesel, who had cousins living in Buenos Aires 12, could have known about Mark Turkov’s Yiddish publishing house and his massive series of WWII “survivor” memoirs. He could very well have read some of them, even the one titled Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, written by a Lazar (Eliezar) Wiesel from Sighet, Transylvania, which may have been passed around within the Yiddish-speaking community before it was published. Wiesel could therefore have used the volume of 245 pages to write a French version for Francois Mauriac.

Could someone have intervened with Mark Turkov to convince him to go along with Elie Wiesel as the author? Sure, they could. And could something have happened to Lazar Wiesel, survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau-Buchenwald, born Sept. 4, 1913, causing him to disappear from the scene? 13 Again, yes, and maybe not even foul play. This is speculation at this point, but nevertheless quite possible.

* * *

Part Two: Can the books Night and And the World Remained Silent have been written by the same author? What one critic reveals.

We know a lot about the man who calls himself Elie Wiesel from his own mouth and pen, but we know of the Lazar Wiesel born on Sept. 4, 1913 only through Miklos Grüner’s testimony, and of the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent) through the work itself. So let’s consider what we know of these two men before we look at their books.

Who is Elie Wiesel?

Elie Wiesel says in Night that he grew up in a “little town in Translyvania,” and his father was a well-known, respected figure within the Hasidic Orthodox Jewish community. However, Sanford Sternlicht tells us that Maramurossziget, Romania had a population of ninety thousand people, of whom over one-third were Jewish.14 Some say it was almost half. Sternlicht also writes that in April 1944, fifteen thousand Jews from Sighet and eighteen thousand more from outlying villages were deported. How many with the name of Wiesel might have been among that large group? I counted 19 Eliezer or Lazar Wiesel’s or Visel’s from the Maramures District of Romania listed as Shoah Victims on the Yad Vashem Central Database. Just think—according to their friends and relatives, nineteen men of the same name from this district perished in the camps in that one year. It causes one to wonder how many Lazar and Eliezer Wiesels didn’t perish, but became survivors and went on to write books, perhaps.

Lazare, Lazar, and Eliezer are the same name. Another variation is Leizer (prounounced Loizer). A pet version of the name is Liczu; a shortened version is Elie.15 In spite of having a popular, oft-used name, Elie Wiesel describes a unique picture of his life. The common language of the Orthodox Hasidic Jews of Sighet was Yiddish. Wiesel has said he thinks in Yiddish, but speaks and writes in French.16

In his memoir, he admits that he was a difficult, complaining child—a weak child who didn’t eat enough and liked to stay in bed.17 He comes across as definitely spoiled, the only son among three daughters.

According to Gary Henry, as well as other of Wiesel’s biographers and Wiesel himself, young Elie Wiesel was exceptionally fervent about the Hasidic way of life. He studied Torah, Talmud and Kabbalah; prayed and fasted and longed to penetrate the secrets of Jewish mysticism to such an extreme that he had “little time for the usual joys of childhood and became chronically weak and sickly from his habitual fasting.”18 His parents had to insist he combine secular studies with his Talmudic and Kabbalistic devotion. Wiesel says in Night that he ran to the synagogue every evening to pray and “weep” and met with a local Kabbalist teacher daily (Moishe the Beadle), in spite of his father’s disapproved on the grounds Elie was too young for such knowledge.

Of his elementary school studies, Wiesel writes: “[My teachers] were kind enough to look the other way when I was absent, which was often, since I was less concerned with secular studies than with holy books.” 19 And “in high school I continued to learn, only to forget.”

But his plans to become a pious, learned Jew came to an end with the deportation of Hungary’s Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Wiesel has told this story both in his first book Night and in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea, and in many talks and lectures.

After liberation, in France, Wiesel met a Jewish scholar and master of the Talmud who gave his name simply as Shushani or Chouchani.20,21 In his memoir, Wiesel wrote:

It was in 1947 that Shushani, the mysterious Talmudic scholar, reappeared in my life. For two or three years he taught me unforgettable lessons about the limits of language and reason, about the behavior of sages and madmen, about the obscure paths of thought as it wends its way across centuries and cultures.22

Wiesel describes this person as “dirty,” “hairy,” and “ugly,” a “vagabond” who accosted him in 1947 when he was 18, and then became his mentor and one of his most influential teachers. Reportedly, when Chouchani died in 1968, Wiesel paid for his gravestone located in Montevideo, Uruguay, on which he had inscribed: “The wise Rabbi Chouchani of blessed memory. His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.” According to Wikipedia, Chouchani taught in Paris between the years of 1947 and 1952. He disappeared for a while after that, evidently spent some time in the newly-formed state of Israel, returned to Paris briefly, and then left for South America where he lived until his death.23

This could be important because it links up with Wiesel’s visits to Israel and his trip to Brazil in 1954. While the common narrative of Elie Wiesel’s post-liberation years focuses on his being a student at the Sorbonne University, Paris and an aspiring journalist, these sources reveal that he was still deeply into Jewish mysticism and involved with the Israeli resistance (terrorist) movement in Palestine.

Wiesel received a $16-a week-stipend from the welfare agencies.24 In addition, he worked as a translator for the militant Yiddish weekly Zion in Kamf. In 1948, at the age of 19, he went to Israel as a war correspondent for the French-Jewish newspaper L’arche, where he eventually became a correspondent for the Tel Aviv newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth.25 Shira Schoenberg at the Jewish Virtual Library puts it this way: “he became involved with the Irgun, a Jewish militant (terrorist) organization in Palestine, and translated materials from Hebrew to Yiddish for the Irgun’s newspaper […] in the 1950s he traveled around the world as a reporter.”26

The above paints a picture of a religiously-inclined personality, strongly drawn to, perhaps even obsessed with, the most mystical teachings and “secrets” of his Judaic tribe. By the age of 15, this trait was well-established. One year in detention of whatever kind (yet to be established for certain), hiding out, or other privations had no power to change these strong interests, which asserted themselves again immediately upon his “release.”

What kind of personality was Lazar Wiesel?

We only know of the Lazar Wiesel who was born on Sept. 4, 1913 through Miklos Grüner , and of the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign through the work itself. Note that I’m not claiming these two are one and the same.

Grüner writes in Stolen Identity27 that after the death of his father in Birkenau “after six months,” which must have been in October or early November 1944, he went to see the friends of my father and brother, Abraham Wiesel and his brother Lazar Wiesel from Maramorossziget, [ …] Abraham was born in 1900 and his tattooed number was A-7712 and Lazar was born in 1913 and was tattooed as A-7713, whereas my father had A-11102, my brother A-11103, and I who stood after my brother finished up with the number A-11104. When they had heard the story of my father, they promised to take care of me and from then on, they became my protectors and brothers and an additional refuge …” (p. 24)

[…]

About three months had passed by, in my stage of hopelessness, I was informed by my “brothers” (Abraham and Lazar) that the Russians had managed to break through and they were on their way to liberate us from “BUNA,” Auschwitz III. (p. 25)

[…]

During the long march […] the walking became difficult and it was also hard to keep up with Abraham and Lazar. That was until I reached a place 30 km from Monowitz “Buna” called Mikolow, with a huge brickyard. Tired as I was after walking under the heavy winter conditions, I fell asleep on a pallet […] When night turned to dawn, I took my time and made my attempt to find Abraham and Lazar […] Later on I managed to find them and for the next 30 kilometres I had no problem in keeping up with them […] up to the next labor camp in Gliwice. After about three days stay in Gliwice, we were ordered to climb up onto an open railway carriage, without any given destination. […] Once again I lost Lazar and Abraham, but […] I found my old friend Karl … (p. 26)

The journey lasted about four days. On our arrival … I wobbled away to search for Abraham and Lazar. After a while, I found Lazar who told me that Abraham was having a hard time of it and he was not sure that Abraham would be able to pull through. He also mentioned that no matter what, he was going to stay with Abraham and was asking for God’s blessing. (p. 27)

[…]

When finally we were given our clothes (after showers, etc), we were registered and received new numbers that we had to memorize like children, and then we were assigned to Barrack 66. (Comment: “we” does not include Lazar and Abraham. Barrack 66 was the children’s barracks in the “small camp” at Buchenwald. Grüner was 16 yrs. old and his father had died.)

About a week later, I couldn’t believe my own eyes to see Lazar in our Block 66. He told me that Abraham had passed away four days after our arrival at Buchenwald. He made it clear that he had received special permission to join us children in Block 66, since he was so much older than us.

Five days before the liberation in April […] In our Block 66, attempts were made to get us to the main gate. The supervisor of our block, called Gustav with his red hair, indeed had managed to drive us out of the block and was determined to drive us to the gate. When we reached the middle of the yard, I pulled my trousers down (halfway), then ran off to the side and kept on running as fast as I could to the nearest block, which I believe was Block 57. I asked the man in the lower bunk if the place next to him was occupied, and I simultaneously took my position in the left hand corner of the bunk, where I remained until I was liberated.

If my memory serves me correctly, on the fourth day after my liberation, AMERICAN SOLDIERS came into the block and a picture was taken of us survivors of the Holocaust. […] This picture has become famous all over the world as a memory of the Holocaust.28 After a change of clothing and a medical examination, I went to look for Lazar, but unfortunately I could not find him anywhere. (p 28)

On page 30, Grüner writes: “When the liberating American soldiers came into our barrack, they discovered a block full of emaciated people lying in bunks. In the next minute a flashlight from a camera went off, and I without my knowing, was caught on the picture forever.”

On page 30, Grüner writes: “When the liberating American soldiers came into our barrack, they discovered a block full of emaciated people lying in bunks. In the next minute a flashlight from a camera went off, and I without my knowing, was caught on the picture forever.”

Grüner never saw Lazar Wiesel again, since, according to him, Lazar was sent to France, and Grüner to a sanatorium in Switzerland. When Grüner was contacted in 1986 about meeting the Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, he thought he was going to be meeting his old friend Lazar Wiesel.

What does Un di Velt Hot Gesvign tell us about Eliezer Wiesel?

Naomi Siedman, Professor of Jewish Culture at Graduate Theological Union, is one of the few academics to delve into Wiesel’s early writings with a critical spirit. Her very controversial essay “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,”29 written in 1996, one year after the publication of Wiesel’s memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea, examines several passages in Night and compares them to passages in the Yiddish original. Among the relevant issues she brings up is this one:

Let me be clear: the interpretation of the Holocaust as a religious theological event is not a tendentious imposition on Night but rather a careful reading of the work.

In other words, Night presents the Holocaust as a religious event, rather than historical. In contrast, Siedman found that the Yiddish version, Un di Velt, published two years prior to the publication of Night, was similar to all others in the “growing genre of Yiddish Holocaust memoirs” which were praised for their “comprehensiveness, the thoroughness of (their) documentation not only of the genocide but also, of its victims.” Un di Velt Hot Gesvign was published as volume 117 of Mark Turkov’s Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry) in Buenos Aires.

Siedman refers to a reviewer of the mostly Polish Yiddish series when she writes:

For the Yiddish reader, Eliezer (as he is called here) Wiesel’s memoir was one among many, valuable for its contributing an account of what was certainly an unusual circumstance among East European Jews: their ignorance, as late as the spring of 1944, of the scale and nature of the Germans’ genocidal intentions. The experiences of the Jews of Transylvania may have been illuminating, but certainly none among the readers of Turkov’s series on Polish Jewry would have taken it as representative. As the review makes clear, the value of survivor testimony was in its specificity and comprehensiveness; Turkov’s series was not alone in its preference. Yiddish Holocaust memoirs often modeled themselves on the local chronical (pinkes ) or memorial book (yizker-bukh ) in which catalogs of names, addresses, and occupations served as form and motivation. It is within this literary context, against this set of generic conventions, that Wiesel published the first of his Holocaust memoirs.

Siedman continues that “Un di velt has been variously referred to as the original Yiddish version of Night and described as more than four times as long; actually, it is 245 pages to the French 158 pages.” But the “four times as long” was referring to the original 862 pages that Turkov cut down to 245. Siedman reminds us that Wiesel had earlier described his writing of the Yiddish with no revisions, “frantically scribbled, without reading.” She says this, and Wiesel’s complaint that the original manuscript was never returned to him, are “confusing and possibly contradictory.” She then writes:

What distinguishes the Yiddish from the French is not so much length as attention to detail, an adherence to that principle of comprehensiveness so valued by the editors and reviewers of the Polish Jewry series. Thus, whereas the first page of Night succinctly and picturesquely describes Sighet as “that little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood,” Un di velt introduces Sighet as “the most important city [shtot] and the one with the largest Jewish population in the province of Marmarosh.” 30 The Yiddish goes on to provide a historical account of the region: “Until, the First World War, Sighet belonged to Austro-Hungary. Then it became part of Romania. In 1940, Hungary acquired it again.”

The great length of the original was no doubt due to the extensive detail it contained about the events, places and people that were the subject of the narrative. Despite the fact that descriptive detail is not a characteristic in any of Wiesel’s known writing, he would never have been able to write all that detail in two weeks in a ship’s cabin, relying only on his memory. He even says he saw no one during that time and cut himself off from everything. In the writing style of Elie Wiesel that we’re familiar with, what could he possibly have said to fill up 862 pages? Impossible!

Another point made by Siedman: And while the French memoir is dedicated “in memory of my parents and of my little sister, Tsipora,” the Yiddish (book) names both victims and perpetrators: “This book is dedicated to the eternal memory of my mother Sarah, father Shlomo, and my little sister Tsipora — who were killed by the German murderers.” 31 The Yiddish dedication is an accusation from a very angry Jew who is assigning exact blame for who was responsible. In addition, this brings to mind the fact that Elie Wiesel’s youngest sister was named Judith at birth, not Tsipora (according to his sister Hilda’s testimony).

Siedman says the effect of this editing from the Yiddish to the French was:

…to position the memoir within a different literary genre. Even the title Un di velt hot geshvign signifies a kind of silence very distant from the mystical silence at the heart of Night. The Yiddish title (And the World Remained Silent) indicts the world that did nothing to stop the Holocaust and allows its perpetrators to carry on normal lives […] From the historical and political specificities of Yiddish documentary testimony, Wiesel and his French publishing house fashioned something closer to mythopoetic narrative.

Myth and poetry … from a very historical and political original testimony. Wiesel attempted to explain this in his memoir by describing his French publisher’s objections to his documentary approach: “Lindon was unhappy with my probably too abstract manner of introducing the subject. Nor was he enamored of two pages (only two pages?) which sought to describe the premises and early phases of the tragedy. Testimony from survivors tends to begin with these sorts of descriptions, evoking loved ones as well as one’s hometown before the annihilation, as if breathing life into them one last time.” 32 Just how convincing that is I leave up to the reader.

The most controversial part of Siedman’s essay is about the Jewish commandment for revenge against one’s enemies. The author of the Yiddish writes that right after the liberation at Buchenwald:

Early the next day Jewish boys ran off to Weimar to steal clothing and potatoes. And to rape German girls [un tsu fargvaldikn daytshe shikses]. The historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled.” 33

This reflects the same angry, stern Jew who demands the Jewish law of revenge upon one’s enemies be followed. He does not consider “raping German girls” to be sufficient revenge; thus he says the historical commandment was not fulfilled. In the French and English, it was softened to: “On the following morning, some of the young men went to Weimar to get some potatoes and clothes—and to sleep with girls. But of revenge, not a sign.”34 Siedman comments on this passage:

To describe the differences between these versions as a stylistic reworking is to miss the extent of what is suppressed in the French. Un di velt depicts a post-Holocaust landscape in which Jewish boys “run off” to steal provisions and rape German girls; Night extracts from this scene of lawless retribution a far more innocent picture of the aftermath of the war, with young men going off to the nearest city to look for clothes and sex. In the Yiddish, the survivors are explicitly described as Jews and their victims (or intended victims) as German; in the French, they are just young men and women. The narrator of both versions decries the Jewish failure to take revenge against the Germans, but this failure means something different when it is emblematized, as it is in Yiddish, with the rape of German women. The implication, in the Yiddish, is that rape is a frivolous dereliction of the obligation to fulfill the “historical commandment of revenge”; presumably fulfillment of this obligation would involve a concerted and public act of retribution with a clearly defined target. Un di velt does not spell out what form this retribution might take, only that it is sanctioned — even commanded — by Jewish history and tradition.

The final passage that Siedman compares is the famous ending of Night. The Yiddish version presents not only a longer narrative, but a radically different person who emerges from his camp experience at the time of liberation.

Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.

One fine day I got up—with the last of my energy—and went over to the mirror that was hanging on the wall. I wanted to see myself. I had not seen myself since the ghetto. From the mirror a skeleton gazed out. Skin and bones. I saw the image of myself after my death. It was at that instant that the will to live was awakened. Without knowing why, I raised a balled-up fist and smashed the mirror, breaking the image that lived within it. And then — I fainted… From that moment on my health began to improve. I stayed in bed for a few more days, in the course of which I wrote the outline of the book you are holding in your hand, dear reader.

But—Now, ten years after Buchenwald, I see that the world is forgetting. Germany is a sovereign state, the German army has been reborn. The bestial sadist of Buchenwald, Ilsa Koch, is happily raising her children. War criminals stroll in the streets of Hamburg and Munich. The past has been erased. Forgotten. Germans and anti-Semites persuade the world that the story of the six million Jewish martyrs is a fantasy, and the naive world will probably believe them, if not today, then tomorrow or the next day.

So I thought it would be a good idea to publish a book based on the notes I wrote in Buchenwald. I am not so naive to believe that this book will change history or shake people’s beliefs. Books no longer have the power they once had. Those who were silent yesterday will also be silent tomorrow. I often ask myself, now, ten years after Buchenwald : Was it worth breaking that mirror? Was it worth it? 35

This entire passage sounds nothing like Elie Wiesel, or anything he has written. It is matter of fact, not indulging in self-pity but addressing the reality of the situation with a cynical eye. The author is concerned with the traditional problems of Jews, as he sees it, and their welfare. His “witness” as a survivor is not mystical or universalized, but is about assessing blame. His depiction of smashing the mirror that holds his dead-looking image, and how that expression of powerful anger and life-affirmation revived him, is convincing. Right away, he wants to write about his experience, and he begins. Anger and “putting it all down” is the way out of depression and listlessness.

Yet the author and editors of Night have removed almost all of this and end very differently:

One day I was able to get up, after gathering all my strength. I wanted to see myself in the mirror hanging from the opposite wall. I had not seen myself since the ghetto.

From the depths of the mirror, a corpse gazed back at me.

The look in his eyes, as they stared into mine, has never left me.36

No anger. No recuperation or recovery possible for this character. No closure. Elie Wiesel leaves us in Night with the image of death, and for the rest of his life he will pour it out on the world through his writings. This is his legacy; the Holocaust never ends.

Siedman comments on these two endings:

There are two survivors, then, a Yiddish and a French—or perhaps we should say one survivor who speaks to a Jewish audience and one whose first reader is a French Catholic. The survivor who met with Mauriac labors under the self-imposed seal and burden of silence, the silence of his association with the dead. The Yiddish survivor is alive with a vengeance and eager to break the wall of indifference he feels surrounds him.

Naomi Siedman intends the “two survivors” to be taken symbolically, as she is a “respected” Jewish academic who does not question the Holocaust story, and does not question (publicly at least) the authenticity of Elie Wiesel as the author of the Yiddish 862-page And the World Remained Silent, no matter what difficulties are encountered. As she continues in this essay, she posits Francois Mauriac’s powerful influence on Elie Wiesel as the way of explaining the further shortening and redirection of the focus of the original text. This is not my position, so I don’t find it profitable to seek for the origins of Night in Mauriac’s Catholic/Christian views. I believe there are sufficient grounds to consider a different authorship for Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, and that neutral-minded, critical thinkers who have an interest in this subject would not object to studying it from this angle.

* * *

Part III: Nine reasons why Elie Wiesel cannot be the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent).

1. The only original source for the existence of an 862-page Yiddish manuscript is Elie Wiesel.

Wiesel’s 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea is the first time he mentions writing this book in the spring of 1954 on an ocean vessel on his way to Brazil.

In the original English translation of Night, Hill and Wang, 1960, there is no mention of the Yiddish book from whence it came. Nowhere does it name the original version and publication date. There is no preface from the author, only a Foreword by Francois Mauriac who was satisfied to simply call the book a “personal record.”

In his 1979 essay titled “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Wiesel declares that his first book was written “at the insistence of the French Catholic writer Francois Mauriac” after their first meeting in May 1955. There is no mention in this essay of a Yiddish book, of any length. By “his first book” he obviously meant La Nuit, published in 1958 in France. 37

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in Dec.1986, Wiesel doesn’t mention his books, but refers twice to the “Kingdom of Night” that he lived through and once says, “the world did know and remained silent.” So it’s not like he was unaware of this book title. 38

Thus, All Rivers Run appears to be the first mention of the Yiddish origin of Night. Why did Elie Wiesel decide to finally write about And the World Remained Silent in that 1995 memoir? Could it have been because in 1986, after being formally awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Stockholm, he was “reunited” with a fellow concentration camp inmate Myklos Grüner, who, after that meeting, read the book Night that Wiesel had given him, recognized the identity of his camp friend Lazar Wiesel in it, and from that moment began his investigation of who this man named Elie Wiesel really was?

Grüner writes in his book Stolen Identity, “My work of research to find Lazar Wiesel born on the 4th of September 1913 started first in 1987, to establish contact with the Archives of Buchenwald.” 39 He was also writing to politicians and newspapers in Sweden. This could not have failed to attract the notice of Elie Wiesel and his well-developed public relations network. Grüner tracked down Un di Velt Hot Gesvign as the original book from which Night was taken, and believed it was written by his friend Lazar Wiesel and “stolen” somehow by “Elie.”40

This could account for why Elie Wiesel suddenly began to speak and write about his Yiddish book, published in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1956. (It was actually inserted into the larger Polish collection in late 1954, according to the Encyclopedia Judaica{see part II}, and printed as a single book in 1955, with a 1956 publication date.) 41

Wiesel claims the 862-page typescript he handed over to publisher Mark Turkov on the ship docked at Buenos Aires in spring 1954 was never returned to him.42 (Wiesel had not made a copy for himself, and didn’t ask Turkov to make copies and send him one, according to what he wrote in All Rivers.)

The only other person reported to ever have had the typescript in his hands was Mr. Turkov, but there is no word from him about it. We can only say for sure that he published a 245-page volume in Polish Yiddish titled Un di Velt Hot Gesvign by Eliezer Wiesel. The book has no biographical or introductory material—only the author’s name. Eric Hunt has made this Yiddish book available on the Internet 43 and is seeking a reliable translator.

There is practically nothing written about Mark Turkov. You can read about his accomplished family here. He was born in 1904 and died 1983. There is no direct testimony from Mark Turkov, that I have been able to find, that he ever received such a manuscript. Since Turkov lived until 1983 to see the book Night become a world-wide best seller, I find this inexplicable. Did no one seek him out to ask him questions, ask for interviews, take his picture? But at the same time, that becomes understandable if Night was not connected with Un di Velt until after 1986, when Miklos Grüner entered the picture and began asking questions.

We’re left with asking: was there ever an 862 page manuscript? And if not, why does Wiesel say he wrote that many pages?

2. Wiesel could not have written the 862 pages in the time he says he did.

According to what he writes in All Rivers, Wiesel’s voyage lasted at most two weeks. Spending all his time in his cabin, cut off from all sources of information, seemingly on the spur of the moment (not pre-planned), he types feverishly and continuously on a portable typewriter (even though he’s written all his other books in long-hand, by his own testimony) and produces 862 typewritten pages without re-reading a single one. That comes out to an average of almost 62 pages daily, for 14 days straight. Is there anyone who could accomplish such a feat?

The scrawny Elie Wiesel is not a superman; he is not even the intense type, but more of a spaced-out thoughtful type. What’s more, he was not even tired out by this marathon effort, but immediately upon the ship docking at Sao Paulo, he became the active spokesman for a group of “homeless” Jews.

A point to consider about the typewriter: He would have used up a lot of ribbons typing that many pages. Ribbons are those inked strips of fabric that the metal characters hit to make the black or color impression on the white paper. This is something the computer generation doesn’t know anything about. The ribbons did not last all that long; the characters on the page got lighter as the ribbon was hit again and again; thus he would have been installing a new one with some regularity. As I recall, replacing the ribbon was not a very fun thing to do. Did he plan on writing day and night, and bring plenty of ribbons with him? Was he able to purchase more ribbons for his particular machine in Brazil?

Another point about the typewriter brought up earlier by a reader: Was Wiesel a fast or slow typist? Many journalists were, and are, two-fingered (hunt and peck) typists because they never took typing classes. Where would Elie Wiesel have learned to type? In the newspaper office? If he was not a full-finger typist, it’s even less likely he could have churned out all those pages. Not to mention that these old typewriters did not allow the ease, and therefore speed, of our modern keyboard. These are practical questions that help us to ground ourselves in reality.

In addition, this manuscript is said to have been written in the style of a detailed history of the entire process of deportation, detention, people and places, punishments, liberation, yet Wiesel has no reference materials on board ship—only his memory. And since it was nine years since the events had ended, certainly some dulling of his memory had occurred. This simply could not be accomplished in the kind of mad rush Wiesel describes in All Rivers.

3. Wiesel’s motivation for attempting to write his concentration camp memories when he did is not given and is not apparent.

It’s astonishing that Wiesel gives only one paragraph in his memoir to the entire process of writing this book. He doesn’t write of thinking about it ahead of time. In fact, just at the time of his trip to Brazil he is carrying on a love affair in Paris, as well as being very busy, enthused and ambitious about his journalist assignments. Hanna, his love interest, had proposed marriage to him and he records in All Rivers that it “haunted me during the crossing,” during which time he “was worried sick that I might be making the greatest mistake of my life.”44 Yet, as though a kind of afterthought, he then tells us he spent the entire crossing holed up in his cabin, feverishly writing his very emotionally traumatic “witness” to the holocaust, even though only 9 years of his self-imposed 10-year vow of silence had passed.

In over 100 pages prior to the trip, Wiesel does not mention wanting to write about or even reflecting on his concentration camp year. The only explanation he includes in that paragraph is: “My vow of silence would soon be fulfilled; next year would mark the tenth anniversary of my liberation.”45 Then, just as suddenly, when he steps on land in Brazil, he is fully engaged in journalism and Hanna once again. He has given the typescript away and seems to have totally forgotten about it.

4. Wiesel had no opportunity to edit the 862 pages of And the World Remained Silent to the 245-page published version, yet he says he did.

Wiesel writes in All Rivers, “I had cut down the original manuscript from 862 pages to the 245 of the published Yiddish edition. French publisher Jerome Lindon edited La Nuit down to 178.”46 The time is 1957 and Wiesel is pleased a French publisher has been found for the manuscript he gave to Francois Mauriac—his French translation of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, of which Wiesel says of the latter, “I had already pruned and abridged considerably.” The publisher, Lindon, now “proposed new cuts throughout, leading to significant differences in length among the successive versions.”

He repeats something similar in his Preface to the new 2006 translation of Night:

Though I made numerous cuts, the original Yiddish version still was long.47

He can only mean the 245-page book as the “original Yiddish version”—thus he “made cuts” from the longer version. But Wiesel could not have done it because he never saw the manuscript again after he supposedly gave it to Mark Turkov. He writes of his extremely busy life following the Brazil trip—covering world events as a journalist, spending time in Israel again before considering moving to NYC. He sounds underwhelmed when he reports receiving a copy of the Yiddish book in the mail from Turkov in Dec.1955, and devotes only a couple sentences to it. 48

Another time he refers to reducing the 245-page Yiddish version into a French version. Speaking of Mauriac:

He was the first person to read Night after I reworked it from the original Yiddish. 49

It is just these kinds of comments that cause the confusion remarked upon by Naomi Siedman in her essay commenting on Jewish rage in Wiesel’s first book. She writes that certain “scholars,” such as Ellen Fine and David Roskies give conflicting reports on the length of Wiesel’s original book, and it’s not clear just which book they are talking about. In my opinion, the reason for all the confusion is that they take Wiesel at his word as an honest witness … perhaps with some memory lapses. They won’t entertain the idea that this is part of a cover-up, the details of which Mr. Wiesel has a hard time keeping straight.

5. Wiesel’s recognized “style” and the style of the Yiddish book are noticeably different.

Not enough is known as yet to non-Yiddish readers like me about the content of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign to make the strongest case for the above statement, but a Jewish critic has provided some passages from the Yiddish book and I will quote from her (except for one passage from Joachim Neander). Naomi Siedman, in her long essay cited above, says this:

For the Yiddish reader, Eliezer Wiesel’s memoir was one among many, valuable for its contributing an account of what was certainly an unusual circumstance among East European Jews: their ignorance, as late as the spring of 1944, of the scale and nature of the Germans’ genocidal intentions. 50

In other words, holocaust narratives had already developed a “Yiddish genre” and the Wiesel memoir fit in with them. She explains:

When Un di velt had been published in 1956, it was volume 117 of Turkov’s series, which included more than a few Holocaust memoirs. The first pages of the Yiddish book provide a list of previous volumes (a remarkable number of them marked “Sold out”), and the book concludes with an advertisement/review for volumes 95-96 of the series, Jonas Turkov’s Extinguished Stars. In praising this memoir, the reviewer implicitly provides us with a glimpse of the conventions of the growing genre of Yiddish Holocaust memoir. Among the virtues of Turkov’s work, the reviewer writes, is its comprehensiveness, the thoroughness of its documentation not only of the genocide but also, of its victims.

[…]

Thus, whereas the first page of Night succinctly and picturesquely describes Sighet as “that little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood,” Un di velt introduces Sighet as “the most important city [shtot] and the one with the largest Jewish population in the province of Marmarosh,” and also “Until, the First World War, Sighet belonged to Austro-Hungary. Then it became part of Romania. In 1940, Hungary acquired it again.” 51

The Yiddish book has a different “feel” to it from Night; not only a different style, but a different personality is behind it. Ms. Seidman told E.J. Kessler, editor of The Forward:

The two stories can be reconciled in strict terms,” she said, “but they still give two totally different impressions, one of a person who’s desperate to speak versus one who’s reluctant.52

Here is a translation by Dr. Joachim Neander of a key passage in the Yiddish book, which he posted on the CODOH forum. It reveals an informal, talkative style, totally different from the spare, literary style used by Wiesel in all his books, even though the storyline is basically the same. Wiesel says he edited this book to its published form, but it doesn’t sound like him.

On January 15, my right foot began to swell. Probably from the cold. I felt horrible pain. I could not walk a few steps. I went to the hospital. The doctor examined the swollen foot and said: It must be operated. If you will wait longer, he said, your toes will have to be cut off and then the whole foot will have to be amputated. That was all I needed! Even in normal times, I was afraid of surgery. Because of the blood. Because of bodily pain. And now – under these circumstances! Indeed, we had really great doctors in the camp. The most famous specialists from Europe. But the means they had to their disposition were poor, miserable. The Germans were not interested in curing sick prisoners. Just the opposite.

If it had been dependent on me, I would not have agreed to the operation. I would have liked to wait. But it did not depend on me. I was not asked at all. The doctor decided to operate, and that was it. The choice was in his hands, not in mine. I really felt a little bit of joy in my heart that he had decided upon me.53

Back to Siedman’s translations. Two examples will have to suffice, from the Dedication and the very last paragraphs.

… while the French memoir is dedicated “in memory of my parents and of my little sister, Tsipora,” the Yiddish names both victims and perpetrators: “This book is dedicated to the eternal memory of my mother Sarah, father Shlomo, and my little sister Tsipora — who were killed by the German murderers.” 54

Now the book’s ending in the Yiddish version:

Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.

One fine day I got up — with the last of my energy — and went over to the mirror that was hanging on the wall. I wanted to see myself. I had not seen myself since the ghetto. From the mirror a skeleton gazed out. Skin and bones. I saw the image of myself after my death. It was at that instant that the will to live was awakened. Without knowing why, I raised a balled-up fist and smashed the mirror, breaking the image that lived within it. And then — I fainted. From that moment on my health began to improve. I stayed in bed for a few more days, in the course of which I wrote the outline of the book you are holding in your hand, dear reader.

But — Now, ten years after Buchenwald, I see that the world is forgetting. Germany is a sovereign state, the German army has been reborn. The bestial sadist of Buchenwald, Ilsa Koch, is happily raising her children. War criminals stroll in the streets of Hamburg and Munich. The past has been erased. Forgotten. Germans and anti-Semites persuade the world that the story of the six million Jewish martyrs is a fantasy, and the naive world will probably believe them, if not today, then tomorrow or the next day.

So I thought it would be a good idea to publish a book based on the notes I wrote in Buchenwald. I am not so naive to believe that this book will change history or shake people’s beliefs. Books no longer have the power they once had. Those who were silent yesterday will also be silent tomorrow. I often ask myself, now, ten years after Buchenwald: Was it worth breaking that mirror? Was it worth it? 55

In contrast, Night ends with the gaze into the mirror at the very beginning of this passage. If the smashing of the mirror and the renewed will to live he felt from it was Elie Wiesel’s own experience, why would he leave it out in La Nuit? Because the publisher wanted it out? Not at all likely. Mauriac? Doubtful. It’s much more likely that it was not Elie Wiesel’s experience and it was not the kind of story he felt he could or wanted to tell.

Also note that the Yiddish writer says he wrote the outline of the book while still in the Buchenwald hospital, and that the published book is based on those notes. Elie Wiesel has never suggested that he began any writing in Buchenwald.

6. Wiesel wrote only one book in Yiddish; all subsequent books are in French.

If we could ask Elie Wiesel why he wrote his concentration camp memoirs in Yiddish, when he was already fluent and writing in French, we would probably get the answer he gave to his friend Jack Kolbert, who was writing a book about him:

“I wrote my first book, Night, in Yiddish, a tribute to the language of those communities that were killed. I began writing it in 1955. I felt I needed ten years to collect words and the silence in them.” 56

Alright. But we should also ask, just how good was Wiesel’s written Yiddish, that he could write this “enormous tome” in such a short time? After Nov. 29, 1947, Wiesel sought out and was given a job with the Irgun Yiddish weekly in Paris called Zion in Kamf. He tells how he was put to work translating Hebrew into Yiddish.

The task was far from easy. I read Hebrew well and spoke fluent Yiddish, but my Germanized written Yiddish wasn’t good. My style was dry and lifeless, and the meaning seemed to wander off into byways lined with dead trees. That was not surprising, since I was wholly ignorant of Yiddish grammar and its vast, rich literature.57

Even though he continued to translate and eventually write for the paper, he also spoke and wrote otherwise in French. He was attending classes at the Sorbonne and reading French classics and the newer existentialists. Following this first and only Yiddish book, Wiesel has done all his writing in French, by his own account—and in longhand, while the Yiddish was written on a typewriter.

It’s hard to reconcile Wiesel’s professed love of Yiddish 58 with his failure to do any writing beyond Un di Velt in that language. It’s suggested it is because Yiddish readers are a diminishing breed. No doubt, but that was already the case in 1954. For what it’s worth, Myklos Gruner records that when he met Elie Wiesel at their pre-arranged encounter in Stockholm in 1986, he asked Elie if he would like to speak in “Jewish,” and Elie said “no.” They ended up speaking together in English.59 Wiesel seems to have no interest in keeping the language alive.

7. Wiesel gives contradictory dates for the writing of his first book, and is fuzzy about what his “first book” is.

Wiesel makes it definite in All Rivers that he wrote the Yiddish book in the spring of 1954, in a cabin of a ship going to Brazil. But around the year 2000 he tells his friend Jack Kolbert:

It took me 10 years before I felt I was ready to do it. I wrote my first book, Night, in Yiddish, a tribute to the language of those communities that were killed. I began writing it in 1955. I felt I needed ten years to collect words and the silence in them. 60

So, is it 1954 or 1955? Wiesel says in All Rivers he met Francois Mauriac in May 1955, one year after his Brazil trip. Mauriac is often credited as the one who convinced Wiesel to end his silence, which culminated in Night. In his 1979 essay, “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Wiesel writes:

Ten years of preparation, ten years of silence. It was thanks to Francois Mauriac that, released from my oath, I could begin to tell my story aloud. I owe him much, as do many other writers whose early efforts he encouraged. But in my case, something totally different and far more essential than literary encouragement was involved. That I should say what I had to say, that my voice be heard, was as important to him as it was to me.

[…]

(H)e urged me to write, in a display of trust that may have been meant to prove that it is sometimes given to men with nothing in common, not even suffering, to transcend themselves.61

He also wrote, in the same essay on the next page (17):

Paris 1954. As correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, I was trying to move heaven and earth to obtain an interview with Pierre Mendes-France, who had just won his wager by ending the Indochina war. Unfortunately, he rarely granted interviews, choosing instead to reach the public with regular talks on the radio. Ignoring my explanations, my employer in Tel Aviv was bombarding me with progressively more insistent cabled reminders, forcing me to persevere, hoping for a miracle, but without much conviction. One day I had an idea. Knowing the admiration the Jewish Prime Minister bore the illustrious Catholic member of the Academie, why not ask the one to introduce me to the other? The occasion presented itself. I attended a reception at the Israeli Embassy. Francois Mauriac was there. Overcoming my almost pathological shyness, I approached him, and in the professional tone of a reporter, requested an interview. It was granted graciously and at once.

Wiesel continues the confusion around ’54 and ’55 when interviewed by the American Academy of Achievement on June 29, 1996 in Sun Valley, Idaho.62 In answer to the question “What persuaded you to break that silence?” he replied:

Oh, I knew ten years later I would do something. I had to tell the story. I was a young journalist in Paris. I wanted to meet the Prime Minister of France for my paper. He was, then, a Jew called Mendès-France. But he didn’t offer to see me. I had heard that the French author François Mauriac […] was his teacher. So I would go to Mauriac, the writer, and I would ask him to introduce me to Mendès-France. […]

Pierre Mendes-France became Prime Minister on June 18, 1954; his hold on that office ended on Jan. 20, 1955. Wiesel, according to his autobiography, had returned from Brazil, after writing and giving his 862-page Yiddish manuscript to Mark Turkov, expressly to cover the inauguration of France’s new Prime Minister for his Israeli newspaper.63 In this case, Wiesel’s first meeting with Mauriac had to be some time after mid-June 1954, since Mendes-France is already Prime Minister; it couldn’t have been in May or June 1955 because Mendes-France was long out of office. But in All Rivers, he puts his first Mauriac meeting in May 1955: “I first saw Mauriac in 1955 during an Independence Day celebration at the Israeli embassy.”(p.258) Israel’s Independence Day is May 14. Wiesel says the interview with Mauriac he obtained from that meeting resulted in his writing La Nuit and sending it to Mauriac one year later, in 1956. He continues describing that meeting to the Academy interviewer:

I closed my notebook and went to the elevator. He (Mauriac) ran after me. He pulled me back; he sat down in his chair, and I in mine, and he began weeping. […] And then, at the end, without saying anything, he simply said, “You know, maybe you should talk about it.”

He took me to the elevator and embraced me. And that year, the tenth year, I began writing my narrative. After it was translated from Yiddish into French, I sent it to him.

Wiesel says “the tenth year,” which would be 1955, but in the earlier part of the interview he is referring to 1954—because of Mendes-France. Since he is mixing up the date, it’s no wonder we find the same mis-dating in stories about Wiesel’s life and accomplishments in books and on the Internet, including on Wikipedia pages.

Whenever it was that Wiesel had that fateful visit with Mauriac, he clearly did not mention that he had already written a very long Yiddish memoir, whether a year or a couple of months earlier. But had he written anything yet? Mauriac never alludes to a first Yiddish text. And as stated before, Wiesel himself didn’t either, until his 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. This is truly noteworthy. Also, the title Un di Velt Hot Gesvign or, in English, And the World Remained Silent does not appear on the long list of “books by Elie Wiesel” at the beginning of All Rivers or the 2006 translation of Night.

To clarify an important problem Wiesel faces here: Wiesel, prior to 1990, claims to have first met and interviewed Mauriac in the spring of 1954 after returning from Brazil, but later changed it to May or June 1955. But even after that, he sometimes reverted to the 1954 scenario. When you are inventing all or parts of your life story, it’s difficult to keep it straight, especially when your guard is down.

A likely reason is his need to fit the writing and publication of the Yiddish book into his “schedule”, something he had not considered, or just ignored, previous to the Yiddish book being brought to the attention of the world by Myklos Grüner.

8. There are striking differences between Night, his “true story” derived from the Yiddish book, and his autobiography All Rivers Run to the Sea.

If Night is a true account of Wiesel’s holocaust experience, how to explain such major differences in the key passages that are compared below. In the first book it is his foot, in the latter his knee that is operated on right before the 1945 evacuation of Auschwitz.

Toward the middle of January, my right foot began to swell because of the cold. I was unable to put it on the ground. I went to have it examined. The doctor, a great Jewish doctor, a prisoner like ourselves, was quite definite: I must have an operation! If we waited, the toes—and perhaps the whole leg—would have to be amputated. .64

[…]

The doctor came to tell me that the operation would be the next day […] The operation lasted an hour.65

The doctor told him he would stay in the hospital for two weeks, until he was completely recovered. The sole of his foot had been full of pus; they just had to open the swelling. But, two days after his operation there was a rumor going round the camp that the Red Army was advancing on Buna. Not able to decide whether to stay in the hospital or join the evacuation, he left to look for his father.

“My wound was open and bleeding; the snow had grown red where I had trodden.” That night his “foot felt as if it were burning.” In the morning, he “tore up a blanket and wrapped my wounded foot in it.” 66

He and his father decided to leave. That night they marched out. They were forced to run much of the night and he ran on that foot, causing great pain. But after that he doesn’t mention it again. By contrast, in All Rivers, it is not his foot, but his knee that is operated on!

January 1945. Every January carried me back to that one. I was sick. My knee was swollen, and the pain turned my gait into a limp. […] That evening before roll call, I went to the KB. My father waited for me outside […] At last my turn came. A doctor glanced at my knee, touched it. I stifled a scream. “You need an operation,” he said. “Immediately.” […] One of the doctors, a tall, kind-looking man, tried to comfort me. “It won’t hurt, or not much anyway. Don’t worry, my boy, you’ll live.” He talked to me before the operation, and I heard him again when I woke up.” 67

[…]

January 18, 1945. The Red Army is a few kilometers from Auschwitz. […] My father came to see me in the hospital. I told him the patients would be allowed to stay in the KB […] and he could stay with me […] but, finally, we decided to leave with the others, especially since most of the doctors were being evacuated too.68

No further mention of the knee. How can we account for this bizarre change from foot to knee? It seems that as weak as Wiesel presents himself to be at Buna, he could not himself believe that he could run around on a foot that had just been operated on for pus in the sole, with no protection. So he simply changed it to his knee.

The next passage is after the liberation of Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. In Night:

Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. We thought only of that. Not of revenge, not of our families. Nothing but bread.

And even when we were no longer hungry, there was still no one who thought of revenge. On the following day, some of the young men went to Weimar to get some potatoes and clothes—and to sleep with girls. But of revenge, not a sign.

Three days after the liberation of Buchenwald I became very ill with food poisoning. I was transferred to the hospital and spent two weeks between life and death.69

In All Rivers, Wiesel changes the story. He writes:

A soldier threw us some cans of food. I caught one and opened it. It was lard, but I didn’t know that.70 Unbearably hungry—I had not eaten since April 5—I stared at the can and was about to taste its contents, but just as my tongue touched it I lost consciousness.

I spent several days in the hospital (the former SS hospital) in a semiconscious state. When I was discharged, I felt drained. It took all my mental resources to figure out where I was. I knew my father was dead. My mother was probably dead ….. 71

From two weeks to only several days spent in the hospital. Could this change have anything to do with the famous Buchenwald survivor photograph 72 that Elie discovered himself in sometime after 1980, when he was actively seeking a Nobel Prize? If he were in the hospital “between life and death” for two weeks following April 14 or so, he could not be in that photograph taken on April 16. The author of And the World Remained Silent, whoever he is, never claimed to be in that photograph.

9. Elie Wiesel refuses to back up his authorship by showing his tattoo.

If Elie Wiesel is the man who wrote Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, the source of the world-famous Night—the same man who wrote about receiving the tattoo number A7713 at Auschwitz in 1944—why won’t he show us this tattoo on his arm? And why do we see video of his left forearm with no tattoo visible at all? Wiesel could so easily clear up this problem, but he doesn’t choose to do so.

Endnotes:

1. “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,” Naomi Seidman, Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, and Society, Fall 1996 (Vol 3, No.1). Online at http://www.vho.org/aaargh/fran/tiroirs/tiroirEW/WieselMauriac.html

2. Ibid.

3, Comment: If this is an assignment by the newspaper for which he is chief foreign correspondent, why does he need or want free tickets? Is this the way Israeli newspapers operated?

4. Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs (New York, 1995), pp. 238-40.

5. Elie Wiesel, Night, translated by Marion Wiesel, (New York, Hill and Wang, 2006), p. ix, x.

6. All Rivers Run to the Sea, ibid. p. 241

7. ibid, p. 242

8. Ibid, p. 267

9. Night, 2006, p. x

10. Encyclopedia Judaica, 2008

11. All Rivers Run to the Sea, p. 277

12. Ibid, p. 241. “In Buenos Aires my cousins Voicsi and her husband Moishe-Hersh Genuth came to meet us. I gave them some articles for the Yedioth Ahronoth. unaware that they would be reprinted or quoted in the American Jewish press.”

13. Miklos Grüner claims that this Lazar Wiesel, his camp friend, is the true author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign and that Elie Wiesel stole both his identity and his book.

14. Sanford Sternlicht, Student Companion to Elie Wiesel, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2003, p. 3.

15. Ibid.

16. First Person: Life & Work. http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/index.html

17. All Rivers Run to the Sea, p. 9

18. First Person: http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/henry.html

19. Rivers, p. 20

20. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Wiesel.html

21. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsieur_Chouchani

22. Rivers, p. 121

23. Wikipedia, Chouchani

24. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_(book) Miklos Grüner says his 32-year-old friend Lazar Wiesel was given an apartment and an income because he had travelled with the orphans to France, under special permission. (see Stolen Identity by Grüner, printed in Sweden, 2007)

25. Wiki/Night

26. Jewish virtual library, ibid.

27. http://www.scribd.com/doc/33182028/STOLEN-IDENTITY-Elie-Wiesel

28. Grüner is speaking of Block 56, where what was to become the “famous Buchenwald liberation photograph” was taken by an American military photographer on April 16, 1945, five days after liberation. See our analysis of this photo under “The Evidence” on the menu bar.

29. “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,” Seidman, ibid.

33. Eliezer Vizel, Un di velt hot geshvign (Buenos Aires, 1956), p. 7

31. Un di velt, n.p.

32. Rivers, p. 319

33. Un di velt, 244.

34. Night, 120.

35. Un di velt, 244-45

36. Night, 120.

37. Elie Wiesel, A Jew Today, Vintage Books, 1979, 260 pg.

38. http://worldsgreatestenglishclass.com/media/ww2/19EWSpeech.pdf

39. Stolen Identity, p. 50

40. bid, p. 43. Grüner mentions the 862 pages twice, but not with proof of their existence. “… Lazar Wiesel’s manuscript […] tell us his story and covers his survival of the Holocaust in 862 pages.” Also, “… had to use Lazar’s false identity in Paris and his existing manuscript of 862 pages …”

41. All Rivers, p. 277. “In December (1955) I received from Buenos Aires the first copy of my Yiddish testimony And the World Stayed Silent,” which I had finished on the boat to Brazil.”

42. Ibid.

43. http://www.megaupload.com/?d=BOQ0UU98

44. All Rivers, p. 239

45. Ibid, p. 240

46. Ibid, p. 319

47. Night, p. x

48. All Rivers, p. 277

49. Ibid. p. 267

50. Siedman, “Jewish Rage”

51. Ibid.

52. “The Rage that Elie Wiesel Edited Out of Night,” E.J. Kessler, ‘The Forward‘, October 4, 1996

53. http://forum.codoh.com/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=6146

54. Siedman, “Jewish Rage,” (trans. from Un di Velt)

55. Ibid. (Un di Velt, 244-45)

56. Jack Kolbert, The Worlds of Elie Wiesel: An Overview of His Career and His Major Themes, Susquehanna University Press, Selinsgrove, PA, 2001, p. 29

57. All Rivers, p.163

58. Ibid. p.291-92

59. Stolen Identity, p.31

60. Kolbert, p. 29

61. ”An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Elie Wiesel, A Jew Today, trans. Marion Wiesel (New York, 1979), p.16

62. http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/wie0int-3

63. All Rivers, p. 242: “I had been away for two months when Dov recalled me to Paris to cover Pierre Mendes-France’s accession to power. I flew back …” This had to be in June 1954.

64. Night, p.82

65. Ibid. p.83

66. Ibid. p.87

67. All Rivers, p.89-90

68. Ibid. p.91

69. Night, p.115-16

70. Why would soldiers throw cans of lard? Sounds terribly disorganized and irregular. How did he open the can? If he didn’t know it was lard, and lost consciousness before he tasted it, we must assume someone in the hospital told him after he regained consciousness that he had been holding a can of lard when he was brought in. Either that or it’s just made up.

71. All Rivers, p.97

72. http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/buchenwald

- Printer-friendly version

- 11254 views