Wishing you a “pig” of a New Year—German style

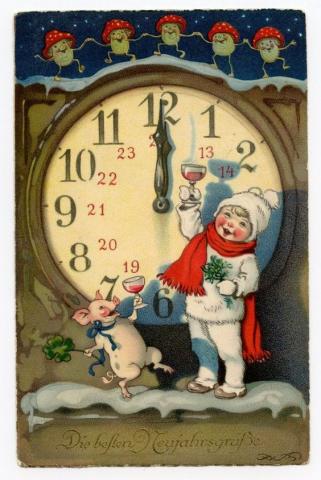

This card reads Die besten Neujahrsgrüsse (The best New Year greetings). I am charmed by the tiny tot and piglet toasting the midnight hour with glasses of wine, and the dancing mushrooms joining in. The pig carries a 4-leaf clover; the boy a sprig of greenery. (click to enlarge)

This card reads Die besten Neujahrsgrüsse (The best New Year greetings). I am charmed by the tiny tot and piglet toasting the midnight hour with glasses of wine, and the dancing mushrooms joining in. The pig carries a 4-leaf clover; the boy a sprig of greenery. (click to enlarge)

By Carolyn Yeager

NO ONE HAS BETTER CARDS THAN THE GERMANS [used to have, anyway]. The pig is the most ubiquitous image in New Year Greetings in Germany going way back. The pig represents prosperity and plenty, as do coins laying around or falling freely for the taking. The four-leaf clover is almost always present, along with the horseshoe, to represent good luck. Then a glass of wine or spirits for good cheer and enjoyment. And, of course, the clock pointing to 12. Sometimes it is a calendar showing Jan. 1st instead.

The image above includes all those elements except the coins, and in addition the dancing mushrooms at the top. Glückpilz (Lucky Mushroom) (left) is a symbol of a blessing at the turn of the New Year in German culture. With its white-spotted bright red cap, it is acknowledged to be the most recognized mushroom on earth and abounds in Christmas decorations, children's story books, and fairy tales. It is believed to bring you good fortune if you should find one—very much the same as the four-leaf clover. They do exist, but are not easy to find. Botanical name: Amanita muscaria

The image above includes all those elements except the coins, and in addition the dancing mushrooms at the top. Glückpilz (Lucky Mushroom) (left) is a symbol of a blessing at the turn of the New Year in German culture. With its white-spotted bright red cap, it is acknowledged to be the most recognized mushroom on earth and abounds in Christmas decorations, children's story books, and fairy tales. It is believed to bring you good fortune if you should find one—very much the same as the four-leaf clover. They do exist, but are not easy to find. Botanical name: Amanita muscaria

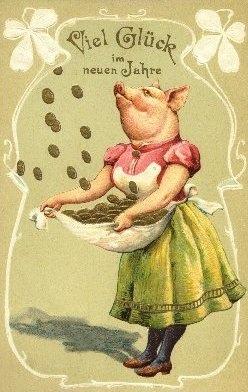

Viel Glück im neuen Jahr (Good luck in the New Year) The pig is now a good hausfrau receiving coins that fall freely into her lap (apron), with the four-leaf clover incorporated into the decorative border. I find this also to be totally charming.

The only element that is missing in these two cards is the lucky horseshoe which is often included with the four-leaf clovers. The pig gives both meat and fat – fat for lard for cooking/baking that was so precious to German people. Unlike what we are taught today by those interested in industrializing our food supply, pork fat and lard are healthy, while soybean, corn, peanut oil and Crisco are not. Real fats feed the brain.

The best of these popular cards seem to be from prior to WWI. I saw a few with the year 1906, '07 and '08 on them, in the great positive years for Germany before the British conspired with their allies to tear Europe apart.

My personal New Year's story

When I was a little girl, it was a tradition for our German male friends and relatives to give out silver dollars to (other people's) children who would recite a fairly long New Year Greeting in German. Since we visited one another's homes on New Year's Day, of course every kid had memorized that New Year greeting, even if butchering the pronunciation pretty good. I collected a handful of silver dollars (which were in currency at the time) every New Year's Day.

I didn't spend my money; I saved it, and I kept those coins in my dresser drawer. Then that fateful day came, that black day when my parents recommended I put my beautiful but heavy silver dollars into a bank account 'all my own', and I willingly handed them over and received a little passbook with my name in it and the amount of my deposit … which was thirty-some dollars, I seem to recall. Little did I, or they, consider that I would never have those silver dollars again, that our currency would devalue to the point that it was not backed by anything tangible.

It would have been nice to have still had those coins in 1980 when the price of silver reached $115.00 an ounce. Or even more to still have them today, just for the pleasure they would bring, and the ability to pass them on. But then, even more valuable as far as money goes would have been so many things I had in the way of toys, books, gadgets that are worth quite a premium as collectors items today. It makes a good case for hoarding.

Happy New Year, readers! Let's resolve that 2019 fulfills the promises of 2016 made by our German U.S. president. I believe he's trying but it's tough to get everything accomplished, so we have to help and firmly demand, not attack. Just like my genuine silver dollars, we won't have him forever.

Tags

New Year 2019Category

Art & Culture- 902 reads

Comments

Loved it, Carolyn! Thank you

Loved it, Carolyn! Thank you and thank you for all your work. Here's to hoping 2019 brings greater gains for the cause of Truth & Justice.

Nice story, thank-you

My Grandmother, (German roots) used to give us a silver dollar on our birthdays. A lot of money back then, especially for her.

Einen herzlichen Gruß

Einen herzlichen Gruß aus Bayern, liebe Carolyn!

Btw: Today the first picture probably would cause a („pol. correct“) tripple shitstorm

⇒⇒⇒

1. Mushrooms – a „no go“ because of anti-drug-laws.

2. A child & alcohol (wine?) – never ever!

3. And: The PIG – RACISM pure! An insult to all Muslims & the Prophet.

Brave new world...

Alles Gute und „viel Schwein“ im Neuen Jahr

Where my silver dollars went ...

The formerly named German-American State Bank circa. 1920.

I just came across a story in my hometown newspaper about the bank I put my silver dollars into. I had known it was a German-owned bank which is why we used it - here's a story published in 2014 for the centennial of 1914 titled "We had to be so careful":

FOR MORE THAN EIGHT DECADES, American State Bank was a mainstay of the downtown banking community. Long associated with the Wochner family and the local German community, the bank survived the anti-German hysteria of World War I and the Great Depression before joining in the rush of bank consolidation in the 1980s.

Brothers Albert and Herman Wochner ran the bank for the better part of four decades, and after a brief interruption with Everett Beal as president, nephew Leonard C. Wochner took charge, passing away in 1983, one year before the bank’s sale to an out-of-town buyer.

Fittingly, American State Bank was first known as the German-American State Bank, as Albert Wochner and other Bloomington businessmen, many of whom were German, raised $100,000 as seed money for a new bank. On May 1, 1902, that exact amount was moved into the old Leader newspaper building on the 100 block of East Washington Street, which became the bank’s first home. “It took several men to carry a small fortune into the new bank’s rooms, where great sacks of gold and piles of greenbacks, silver certificates and other forms of currency, including small change, were stacked on the counters,” reported The Daily Bulletin.

After a short time, the bank relocated to the Unity Building on the east side of the courthouse square before finding (in 1923) permanent quarters on the same block. The new site, 211 N. Main St., was the former Metropole Hotel, once a popular stopover for traveling salesmen owned by local brewers Meyer & Wochner (including Albert).

The main banking room featured marble, black walnut woodwork and lighting fixtures of bronze statuary. The steel door for the safe deposit vault — believed to be the heaviest in Central Illinois — weighed more than 10 tons.

German-American Bank was one of many expressions of the size and influence of the local German community. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, church services, school classes and meetings were often conducted in German. There was a German-language weekly newspaper; German churches, including St. Mary’s Catholic and Trinity Lutheran; and active German organizations, such as the Turnverein (or Turners), with a gymnasium and meeting hall south of downtown.

Alas, a wave of anti-German hysteria gripped the U.S. in 1918 upon entry into the “Great War” (now known as the First World War). “Get right or get out,” was the warning of the local Council of Defense, which passed resolutions making it a crime to print any paper or publication in German, while German communities near Colfax and Anchor were the target of “superpatriot” mobs.

Given such an ugly climate, German-American State board of directors met on April 1, 1918, agreeing to excise the word “German” from the bank’s name. The change, it was said, demonstrated the institution’s willingness to become “100 percent American.” (CUT)

But in 1950, it was still the bank most German-Americans did business with. Our German-American Family Society, begun by my grandfather's generation at that time, also changed it's name to the American-Hungarian Family Society. The problem is: the American government was and is not "100% American."